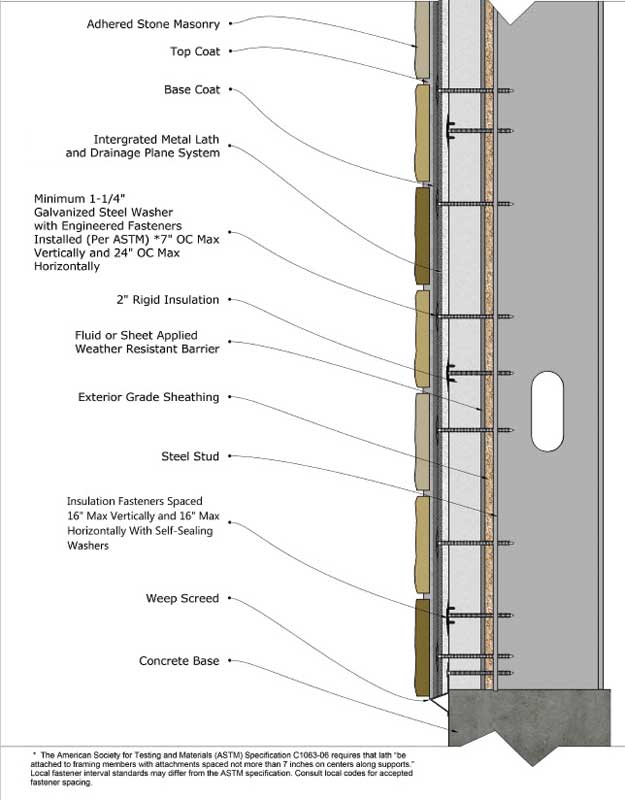

Why drainage and ventilation are critical for adhered masonry walls

Sheathing

This article will now cover moisture behaviour in plywood and oriented strand board (OSB), but is not recommending one sheathing type over the other. Sheathing manufacturers are constantly improving their products, so it is best to check with them about their most recent products’ water absorption and drying characteristics before making a design decision.

Water in the substrate can potentially lead to mould growth, as well as structural, fastener, and veneer degradation. Water damage in this area can be made worse by using OSB sheathing instead of plywood. According to Joe Lstiburek of Building Science Corporation, use of OSB is important when it comes to water management behind adhered veneers because it reacts to moisture very differently than plywood. (For more information, see Lstiburek’s “BSI-029: Stucco

Woes–The Perfect Storm.”)

Plywood becomes more vapour-permeable as it gets wet, going from about 0.5 to 1.5 perms to more than 20 perms, which means its drying rate will increase as it gets wetter. However, OSB’s vapour permeability—and therefore its drying rate—stays low and relatively unchanged no matter how wet it is. Water in plywood also moves laterally much more easily than it does in OSB, so it will migrate out faster and have a significantly lower tendency to concentrate in one area. With OSB, moisture will concentrate at the OSB/building paper interfaces, which can cause localized moisture stresses and damage such as softening, swelling, delamination, and fastener pullout. Moisture is most likely to collect around wall openings. With stucco veneers, control joints—especially horizontal joints—can also collect and hold water, meaning cracks most often appear around windows, doors, and control joints first. (From “The Performance of Weather-resistant Barriers in Stucco Assemblies” by Karim Allana of Allana Buick & Bers Inc., presented at October 2016’s RCI Symposium on Building Envelope Technology.)

Water moves through the pores of masonry from wetter to drier areas. If enough water stays in contact with the masonry long enough, it saturates the masonry by distributing itself throughout via capillary action. While the rate at which a masonry wall dries depends on temperature, humidity, wind, altitude, and sun exposure, a good rule is it takes about 30 days for water to move 25 mm (1 in.) in porous masonry. Since a scratch coat and the mortar used to hold the veneer are, together, normally close to 25 mm thick, adhered masonry walls without drainage and ventilation that are exposed to wetting events more than once every 30 days are unlikely to fully dry once the masonry becomes saturated.

Continuous insulation

Continuous insulation creates a high level of thermal resistance so heat will not easily move through the wall—a good thing for occupant comfort, but not so good for drying. In poorly insulated buildings, temperature differentials between the interior and exterior walls create a heatflow across the wall that warms moisture within it, in turn making the moisture move through the wall as vapour.

Combining this high vapour movement with lots of air leaks means the wall and veneer dry efficiently, because the vapour is carried away by the air movement. More-efficient insulation means less heatflow, and therefore less vapour movement. Compounded with the much-lower airflow inside today’s relatively airtight walls, this makes for much less drying.

Claddings in cold climates operate at colder temperatures in a CI-insulated building, so if the cladding temperature is at or below the dewpoint, any water vapour that touches it will condense into liquid water more readily than if the cladding is close to the same temperature as an uninsulated substrate. Colder claddings also go through more freeze/thaw cycles and will freeze harder than warmer claddings, so water in the wall has the potential to cause more damage. Finally, OSB and plywood sheathings may increase in moisture content during heating periods as insulation efficiency rises, because conditioned warm air inside the building carries moisture that gets absorbed by the sheathing but cannot move past the insulation. Modern insulation approaches mean more moisture in the sheathing, more moisture in the masonry, and more trouble if it does not get out.