When One Theatre Becomes Two: Combining the old and the new to deliver exceptional acoustics

The Lyric Theatre

Once the Greenwin Theatre was completed, the focus turned to the Lyric, which was a more-elaborate project. With the fly tower of the main stage now behind a concrete wall, the stage of the Lyric Theatre was built within the existing audience chamber of the main stage, over the original orchestra pit and first 10 rows of seating.

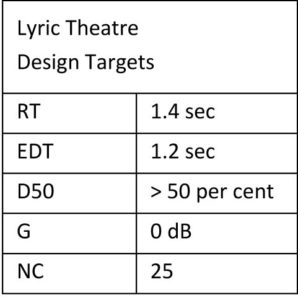

With respect to the reverberation time and background noise levels, the targets are listed as 1.4 seconds and NC 25, respectively (Figure 2). These were essentially the conditions present in the original hall—the desire was to maintain these levels for the new theatre.

The challenge with the Lyric Theatre, like the Greenwin, was to find a way to make a more-intimate venue within the much-larger original space and create an excellent acoustic experience similar to the original hall. As the original hall already had a design strategy incorporating sufficient acoustic absorption for amplified performances, the approach here was to see whether the new space could rely on the design of the original. The new theatre was built using an interior shell with strategically located panels to achieve the acoustical goals.

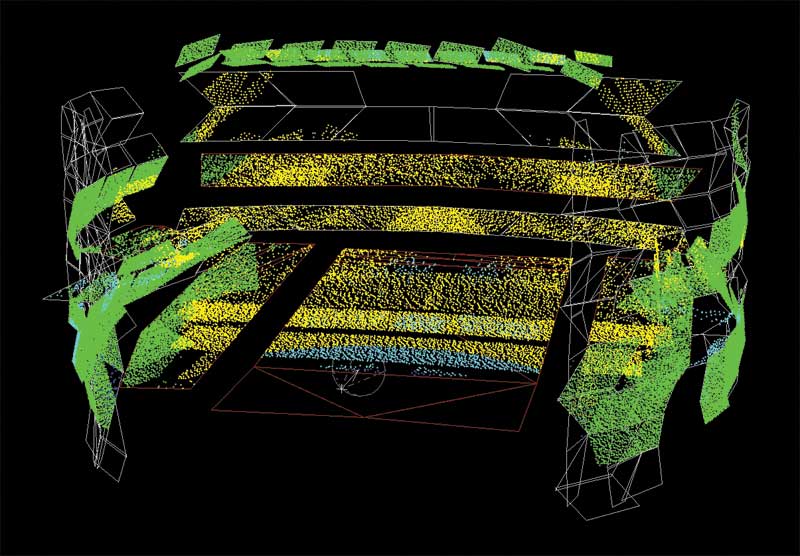

The new shell (i.e. walls) of the Lyric Theatre was constructed from a unique system made up of individual interlocking chevron boxes, which were essentially steel boxes constructed in a chevron pattern, imagined like a Lego block system. The chevrons were located and angled using computer software and modelling programs to ensure they would be able to get the sound energy to the audience at the right time and place.

Each of these chevron boxes was designed to be acoustically different. Some were intended to be acoustically transparent, allowing acoustic energy to escape and reach the absorption on the walls. Others were designed to be acoustically reflective, keeping useful early acoustic energy within the new shell. In addition to being a part of the acoustic design, the chevrons are also used as a lighting feature. The boxes are covered with translucent material and feature light-emitting diode (LED) backlit acoustic panels that can change colour to create different moods depending on theatrical needs.

Image © Aerocoustics Engineering

For the Lyric Theatre, the team reused as many existing materials as possible. For example, the acoustical engineers determined some of the old balconies and upholstered chairs should stay, because they would help create a better acoustic environment even if they could not be seen. This reduced the amount of additional acoustic absorption that needed to be added, and by keeping the old seating intact but hidden from view, the theatre could be returned to its original setting if desired.

Conclusion

For all performance venues, the key measure of success is to see how well-used the space is. Early indications of space usage at the new TCA are promising, and the reception has been positive. The ability to take advantage of the original hall and create a customizable shell utilized for acoustics, lighting, and the overall esthetic in the Lyric was an exciting challenge that pushed the envelope of design and functionality. In the Greenwin, the ability to create a dramatic space while maintaining a sense of acoustic intimacy allows people to consider alternative approaches to the traditional ‘black box’ theatre.

Despite the project constraints, the design and construction of these theatres proved to be successful, and will pave the way for more projects of this kind. As many other performing arts venues struggle with under-utilization, The Toronto Centre for the Arts redesign may serve as a promising case study for many others.

Steve Titus, B.A.Sc., P.Eng., brings more than a decade of experience to being president/ CEO of Aercoustics Engineering Limited, a privately held firm specializing in fostering innovation in acoustics, vibration, and noise control. Over his career, he has been responsible for the acoustical design and delivery of several high-profile projects such as the Sick Kids Research Tower, Corus Quay, Thunder Bay Courthouse, and St. Lawrence Market North redevelopment. Titus is co-chair for Canstruction Toronto, and he sits on the Finance and Audit Committee of the Consulting Engineers of Ontario (CEO). He can be reached via e-mail at stevet@aercoustics.com.

Steve Titus, B.A.Sc., P.Eng., brings more than a decade of experience to being president/ CEO of Aercoustics Engineering Limited, a privately held firm specializing in fostering innovation in acoustics, vibration, and noise control. Over his career, he has been responsible for the acoustical design and delivery of several high-profile projects such as the Sick Kids Research Tower, Corus Quay, Thunder Bay Courthouse, and St. Lawrence Market North redevelopment. Titus is co-chair for Canstruction Toronto, and he sits on the Finance and Audit Committee of the Consulting Engineers of Ontario (CEO). He can be reached via e-mail at stevet@aercoustics.com.

Kiyoshi Kuroiwa, B.A.Sc., P.Eng, created and leads Aercoustics’ contract administration department. He is responsible for the acoustic design and contract administration of architectural projects such as the Aga Khan Museum and Ismaili Centre in Toronto, Simon Fraser University School for the Contemporary Arts in Vancouver, and Mount Allison University Purdy Crawford Teaching Centre in Sackville, N.B. Kuroiwa has applied his experience playing piano and percussion in orchestras to the acoustical design of projects. He can be reached at kiyoshik@aercoustics.com.

Kiyoshi Kuroiwa, B.A.Sc., P.Eng, created and leads Aercoustics’ contract administration department. He is responsible for the acoustic design and contract administration of architectural projects such as the Aga Khan Museum and Ismaili Centre in Toronto, Simon Fraser University School for the Contemporary Arts in Vancouver, and Mount Allison University Purdy Crawford Teaching Centre in Sackville, N.B. Kuroiwa has applied his experience playing piano and percussion in orchestras to the acoustical design of projects. He can be reached at kiyoshik@aercoustics.com.