When One Theatre Becomes Two: Combining the old and the new to deliver exceptional acoustics

The Greenwin Theatre

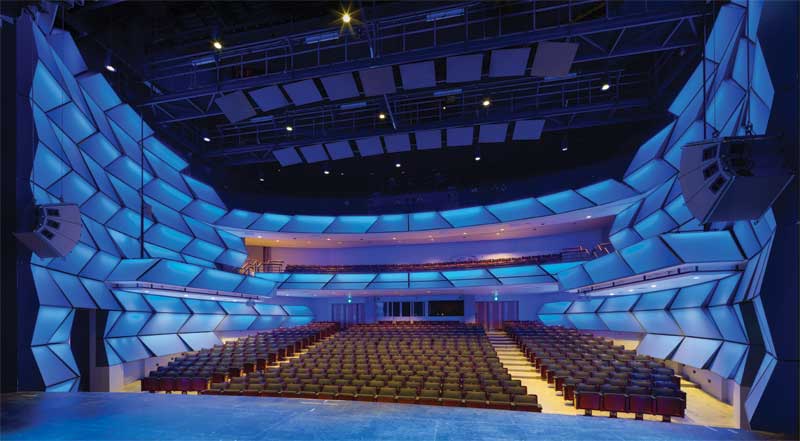

The Greenwin is the smaller of the two newly created theatres. Its foundation is based on the stage and backstage areas within the existing fly tower of the main stage. Although the Greenwin is a more-intimate venue, there is nothing small about its physical presence. As a result of being constructed in the fly tower, the Greenwin is extremely tall and occupies a large volume. This significant physical volume is uncommon for a drama theatre and results in a very high reverberation level, which posed significant acoustical challenges and needed to be tightly controlled, since the theatre is designed primarily for drama. The 25-m (80-ft) tall fly tower is prominently featured as part of the design, but acoustic absorption was incorporated to optimize the acoustics in the space.

The acoustic challenge with this theatre was the volume of the space. The desire was to have a level of intimacy, but this is hard to accomplish when its large, open nature can mean the reverberation is relatively high. The simplest acoustic solution would have been to put a drop ceiling in to decrease the space’s height. However, the client wanted to maintain the dramatic effect of being able to see the fly tower and rigging.

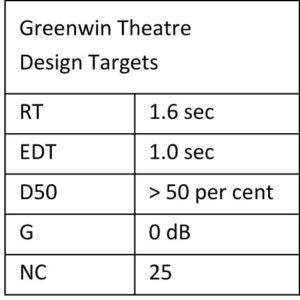

With respect to the ambient background noise, the goal was to maintain the background sound level previously present, which was NC 25 (Figure 1). While the RT in the Greenwin Theatre is higher than this type of space is normally designed for, the goal was to keep EDT—the subjective impression of reverberance—low, and increase D50 to improve speech intelligibility.

Once the targets were set, the team used computer modelling to determine where to place material to help with noise, reverberation, and acoustics. For example, curved ceiling reflectors were added to the design to provide the necessary angle to get the sound energy from the stage into the audience and ensure it did not dissipate into the fly tower. The reflectors were strategically designed and located to optimize the D50 and maximize the energy that could be sent to the audience within the first 50 milliseconds.

A significant amount of absorption was incorporated, with drapery and curtains used in the tower and along the walls. The use of drapery yielded the benefit of being able to ‘tune’ the sound in the venue, increasing or decreasing reverberation by moving, opening, and closing curtains to expose some walls over others. Ultimately, the design allowed the reflectors to provide useful early acoustic reflections to the audience, while drapery absorbed and minimized late acoustic energy reflections. Coupling this with a low background sound level allowed the overall speech intelligibility in the space to be optimized.

Photo © Tom Arban

The design objectives were successfully achieved in the Greenwin, but more importantly, the vision of converting the old fly tower into its own unique venue was fully realized. The experience in this venue is unlike any other drama theatre. Guests entering it are immediately exposed to the dramatic effect of seeing the rigging and the high ceiling, yet the acoustic experience is still intimate.

Building the wall

Given the two theatres had to be built within the existing space and could not be physically separated into isolated structures, the challenge was to create a divide between them to limit sound transfer. Typically, with sensitive performance venues, the levels of separation and isolation are designed to ensure noise intrusions do not affect the experience under simultaneous amplified use. This often results in designs requiring STC 70 or higher.

The level of separation or isolation required to achieve this is substantial, and typically would require a ‘room-within-a-room’ construction. With this style of construction, the performance hall would quite literally have been constructed as an independent room within an existing room, supported by vibration isolation rubber or springs. Essentially, the inner room is ‘floating,’ and there are no rigid contact points between it and the outer room. This is done to ensure there are no conduits for noise to pass from the outer structure to the floating one, and anything that crosses this boundary (i.e. ductwork, sprinklers, and other building services) must be acoustically detailed. Given the constraints of this project, it was not feasible to provide this level of separation.

The solution was to create a double-wall system between the theatres by incorporating a single masonry wall with a separate drywall assembly on the Lyric Theatre side. To ensure solid isolation, the designers used two layers of 16-mm (5/8-in.) drywall for the metal-stud wall and filled it with 100-mm (4-in.) fibreglass acoustic batt insulation. The access corridor between the two theatres was used to create an additional acoustic buffer.