Walls, ceilings, and indoor air quality

Photo © Kelpfish/Dreamstime.com

All interior finishing materials should also be installed two to four weeks before occupancy. This allows time for the building to ‘air out.’ It is important to ensure any materials containing potentially high chemical levels are installed as early as possible during construction to allow for maximum off-gassing before occupancy. Additionally, it is critical to make certain the relative humidity (RH) is below 65 per cent. Not only does high relative humidity cause moisture buildup (a precursor to mould growth), but it can also exacerbate the sink effect in certain products, such as carpeting. (See the August 2008 edition of Environmental Science and Technology [vol. 42, no. 15]).

Another issue is pollution migration. Research has shown VOCs can move from one area of a built environment to another, compromising the indoor air quality of spaces that might appear free of contaminant sources. (See the October 2010 Indoor Air (vol. 20, no. 5). Pollutant migration can occur when airborne contaminants enter and travel through air pathways. Examples of these pathways include the voids between ceiling joists and ceiling plasterboard or the cavities behind electrical outlets and ceiling light fixtures. In addition to VOCs, mould spores, insect and rodent fecal matter, and other indoor pollutants can migrate along the same routes. Contractors should take great care to seal potential air pathways to limit this phenomenon.

Ways to manage IAQ

To protect an interior space’s indoor air quality, great attention must be paid both to material selection and the overall execution of construction. The process of creating a building with good indoor air quality comprises a series of interdependent steps in which failure of one causes subsequent failure of the others. It is therefore incumbent on the project team to ensure each stage of construction is carried out with the overall goal of good IAQ.

Source control

Specifying materials bearing the “GREENGUARD Certified” mark can help ensure those building products have been tested for low chemical emissions. The GREENGUARD Environmental Institute develops third-party chemical emission standards and requires certified products to pass routine testing on an ongoing basis.

Since its inception in 2001, GREENGUARD has certified more than 12,000 products from over 370 manufacturers worldwide. A free database on its website makes it easy to find and search for these products by category, manufacturer, sustainable credit, certification, or keyword. This significantly reduces the time specifiers must spend on researching products and finding those that qualify for sustainable building points.

Construction site management

During new construction of a sensitive environment such as a school, it is critical to have an interior moisture control plan in place to prevent mould growth. If weather or plumbing leaks cause moisture or wetness in the building’s interior, additional materials should not be installed until the building is properly dried out.

All pre-installed materials should be thoroughly inspected for mould and mildew. If they are contaminated, they should be removed immediately. GREENGUARD’s American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standard—ANSI/GEI MMS 1001, Mould and Moisture Management Standard for New Construction—provides further guidance.

While ANSI/GEI MMS 1001 is applicable to commercial and multi-use construction projects in Canada, Canadian Construction Association (CCA) also provides general suggestions on mould management issues via CCA 82, Mould Guidelines for the Canadian Construction Industry. (Visit www.cca-acc.com/documents/cca82/cca82.pdf).

Scheduling and product installation sequencing

Minimizing building products’ onsite storage time also minimizes their risk of exposure to moisture. Therefore, material shipment and delivery should always be based on actual construction progress. On delivery, products should be inspected not only for conforming to the final construction materials list, but also to ensure they are free from water and moisture damage.

Further, outdoor air ventilation should be supplied during the construction to help dilute contaminants and flush them out of the building. The use of temporary construction ductwork is recommended.

Photos courtesy Air Quality Sciences

HVAC operations during construction in occupied buildings

If construction or remodelling must be conducted when the building is occupied or in use, the construction area must be depressurized at a rate at least 10 per cent greater than the supply. Should this be impossible, existing spaces need to be pressurized. Supplemental containment barriers need to be erected if the pressurization is inadequate for controlling construction dust and odours in occupied areas.

It is important not to place construction equipment or staging areas near air intakes for existing construction. Avoiding this helps prevent entrainment of vehicle exhaust, including carbon monoxide, particles, and VOCs. When high-emitting construction activities are performed near outdoor air intakes for existing construction, intake dampers should be temporarily sealed.

During demolition or construction in existing spaces, the HVAC system should not be operated. Further, the supply and return openings should be temporarily sealed with plastic sheeting. If the system must be operational, temporary minimum efficiency reporting value (MERV) 8 filters can be installed in return openings—they must remain clean, of course.

Building flush-out

Following completion of interior finishes and installation of new furnishings, the building should be flushed with 100 per cent clean, outdoor air for two to four weeks before occupancy. This assists in reducing VOCs and other pollution levels. Testing the air for low levels of VOCs before occupancy—with and without flushing—is also highly recommended.

IAQ testing

For new construction and major remodelling, it is important to test the building’s IAQ before occupancy. Measurements should follow protocols established by reputable standard-setting organizations or public health agencies, such as GREENGUARD and ASTM International.

Air samples should be taken either for every 280 m3 (25,000 cf) or for each contiguous floor area—whichever is greater—and be collected in the breathing zone of the air at 1.2 to 2.1 m (4 to 7 ft) above the floor. Areas with the least ventilation and greatest presumed source strength should be included. The building’s HVAC system should operate at normal daily start and stop times at minimum outside airflow for occupied mode for the duration of testing.

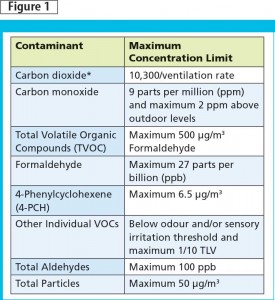

Contaminant concentrations should not exceed the maximum limits in Figure 1. If this happens, additional flush-out with outside air is required, along with re-testing of the air in the same sampling locations until an acceptable level is achieved.

Moisture and mould

Perhaps counter-intuitively, cold temperatures and dry air across much of Canada can contribute to moisture development and mould growth within built environments. This is due largely to high temperature and humidity gradients: the colder and drier the air is outside, the more building occupants rely on heat and humidification inside for both comfort and safety. However, when warm, humid indoor air comes into contact with cold surfaces—such as exterior walls—condensation can form, leading to soggy sheathing and insulation and, consequently, mould growth.

To reduce risk of moisture formation caused by temperature and humidity gradients, one can install batt insulation with the facing (i.e. vapour retarder) toward the source of the warm, moist air. This means in cold climates, the vapour retarder should face the interior. By contrast, in the hot, humid climates well south of Canada, the vapour retarder should face the outside.

The maritime climate of southern British Columbia has moderate temperatures but high rainfall and humidity. Since temperature gradients between the indoors and the outdoors are not as extreme, there is less risk of condensation. However, the issue remains a concern due to the increased rainfall and persistent damp conditions. Additionally, the high rainfall levels and prolonged rainy season in the region are very unforgiving of even minor leaks in walls and roofs.

Conclusion

Not only is optimal indoor air quality critical for the health of building occupants, but it is also important in reducing the risk of legal and financial damages to designers, product manufacturers, builders, building owners, and occupants.

IAQ problems and the resulting illnesses and economic damages can also have legal and financial implications for all parties, including designers, builders, product manufacturers, building owners, employers, and occupants. According to a report by the Building Ecology Research Group, legal issues surrounding IAQ are becoming increasingly common, as are worker compensation claims. Former building occupants, employers, and owners have been known to sue designers, owners, manufacturers, and contractors for millions of dollars.

To construct a building with good IAQ, a project team must take an integrated approach to design and construction. By doing everything possible to ensure good air quality within a building, architects, builders, and facility managers can take pride in knowing they have helped created a healthier indoor environment.

Rachel R. Belew is public relations and communications manager at the GREENGUARD Environmental Institute in Atlanta, Ga. Her articles on green building and design have appeared in various interior design and architectural trade publications. Belew holds a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University in New York City. She can be contacted via e-mail at rbelew@greenguard.org.