Using reflective foil as a vapour barrier

Results and discussion

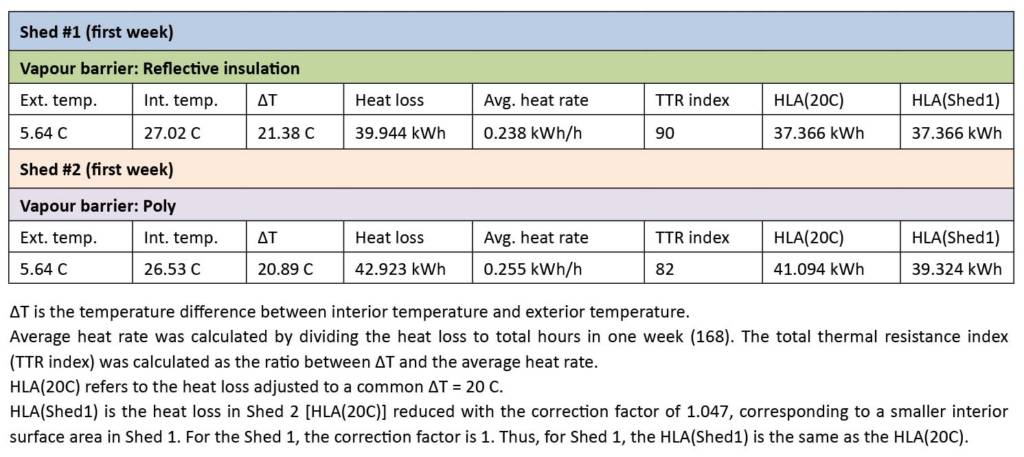

Figure 3 shows the recorded temperatures, energy consumptions (heat loss), and the calculated adjustments during the first week of measurements.

After one week of data readings and all the adjustments made, energy savings associated with upgrading to reflective foil were 1.959 kWh. In other words, the shed with reflective foil as vapour barrier required 4.8 per cent less energy for space-heating than the shed with poly vapour barrier.

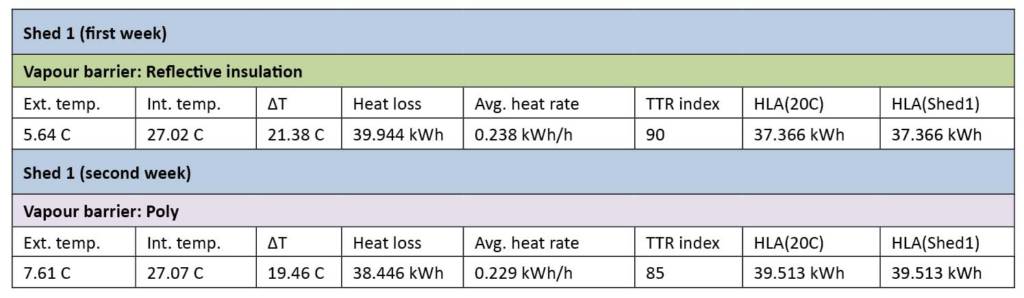

To avoid potential errors from differences between the two sheds, the experiment was replicated for a second week by replacing the reflective foil with regular poly vapour barrier in Shed 1. The straps were reattached—therefore, the 25-mm (1-in.) air space between the drywall and vapour barrier was still in place.

Figure 4 shows the comparative results after recording data for two subsequent weeks in Shed 1. The energy savings, calculated after adjusting the heat loss to a common DT = 20 C (36 F), were 2.147 kWh or 5.4 per cent—relatively close to the initial calculated energy savings of 4.8 per cent, recorded after one week, between Sheds 1 and 2.

Introducing a new energy performance rating index

The EnerGuide rating system (EGRS) was introduced by Natural Resources Canada (NRC) to help builders and homebuyers better understand and implement upgrade opportunities for increasing the energy efficiency of houses. This can translate into energy and money savings, along with significant reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Since EnerGuide’s objective is to increase the energy efficiency of new residential building structures, its recommendations must be applied at the design stage and incorporated during the construction phase.

Software has been developed to assist energy consultants with modelling the energy usage of individual house units based on several key indicators, including:

- home’s dimensions;

- building envelope and technique;

- HVAC systems; and

- climatic related data.

Although processing this type of information can be time-consuming, it is significantly facilitated by the available input on building practice, material, and product choice from existing building plans.

Unfortunately, rating old homes for energy performance has always been more of a challenge—especially when analytical methods are employed. In most cases, building plans are no longer available, so details of the building practice are missing.

Some of the material insulation characteristics may have been altered by time or renovation. Airtightness may have also been affected by continuous usage of windows and doors. Measuring the interior house’s dimensions can be extremely time-consuming, given the absence of the building plans. Employing past utility bills for assessing energy consumption can be an option, but rough estimates on heating systems efficiencies (and also on the energy use behaviour of individual occupants in regard to their preference for thermal comfort) must be addressed. This can significantly affect the accuracy of the results. Moreover, any energy calculation based on past consumption needs to be normalized with weather data for that specific period.