The Sustainable Success of Earth Rangers: A really smart environment

By Andy Schonberger, P.Eng, MBA, LEED AP

Located just north of Toronto, the Earth Rangers Centre (ERC) is a smart, green building that continues to adopt new technologies and strategies to meet its financial and sustainability goals. It was designed 15 years ago with advanced and progressive strategies to reduce the building’s environmental footprint. The facility also uses a thermal mass structure to enable its HVAC strategies and energy conservation aims.1

The Earth Rangers organization teaches children and families about the importance of protecting animals and their habitats, with its headquarters serving as proof the group practises what it preaches. Additionally, the organization uses technology to reach out to kids—through social media, online games, website content, television, and in live community venues—so it should come as no surprise Earth Rangers has been quick to realize the benefits of a ‘connected’ environment in its headquarters.

Moving forward with technology

Proof of this technology and sustainability integration is evident on arriving at the building, located on the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority’s Kortright Centre, in Vaughan, Ont. Six large solar photovoltaic (PV) arrays that tilt and turn to track the sun are situated in the parking lot. These arrays combine the output of 330 solar panels to provide up to 100,000 kWh annually in clean energy, generating up to $44,000 per year from the Ontario Power Authority’s (OPA’s) Feed-in-Tariff Program.2 A second smaller array provides additional power, bringing the onsite generation total to approximately 20 per cent of the ERC’s annual energy consumption.

Efforts at the ERC from 2008 have largely focused on energy conservation, often turning to technology to attain conservation goals. This process started in 2009 with an American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) Level 2 building audit where Earth Rangers’ consulting engineers examined the building’s system performance in fine detail and compared actual performance to design specifications. This audit provided a detailed examination of the building’s energy and water use on a system-by-system basis and it provided a budgeted plan to push the building to carbon neutrality. This involved some major systems retrofits, including the retrofit of a ground-source heat pump system, demand control ventilation, and a modern building automation system to bring together previously unconnected building systems: lighting, security, HVAC, access control, and energy monitoring. The automation system has proven an important part of the integration puzzle, as the more than 300 monitored points in the building allow precise tracking of consumption and system performance.

Integration of technology within the ERC led to total energy consumption of approximately 9 ekWh/sf—a decrease of approximately 18 per cent from the pre-retrofit period, and less than a third of the energy used in a typical Canadian office building.3 There was also a dramatic 100-tonne annual decrease in the centre’s carbon footprint as a result of the switch from natural gas-fired heating to an electrically powered ground-source heat pump. Platinum certification of the ERC under Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) for Existing Buildings: Operations and Maintenance (EBOM) program followed in September 2012, complementing the Gold certification obtained in 2006 for the New Construction (NC) program.

The LEED rating system has helped push green buildings into the mainstream, with more than 1400 certifications completed in Canada. The market forces pushing green buildings forward continue to do so, and technology is increasing their rate of adoption. For instance, a quick scan of industry headlines shows the installed cost of solar photovoltaic generation has dropped 50 per cent since 2010.4

Retrofitting

Technology retrofits at the ERC, as well as commissioning and system integration, have led to reduced HVAC and lighting loads. As an example, the building automation system can communicate with the building’s alarm system, allowing it to shut off unnecessary lighting when the building is armed and unoccupied. Not all loads have trended down, however, as plug loads have continued to grow along with the organization. Load on the building’s uninterruptible power supply (UPS) grew 40 per cent from 2010 to 2013. This is partially due to occupancy increases, but also due to extra plug loads such as computers, monitors, printers, and other distributed office components. There are also unique requirements for energy use in Earth Rangers’ animal care areas, such as the heat lamps required to keep reptile and amphibian animal habitats at proper temperatures.

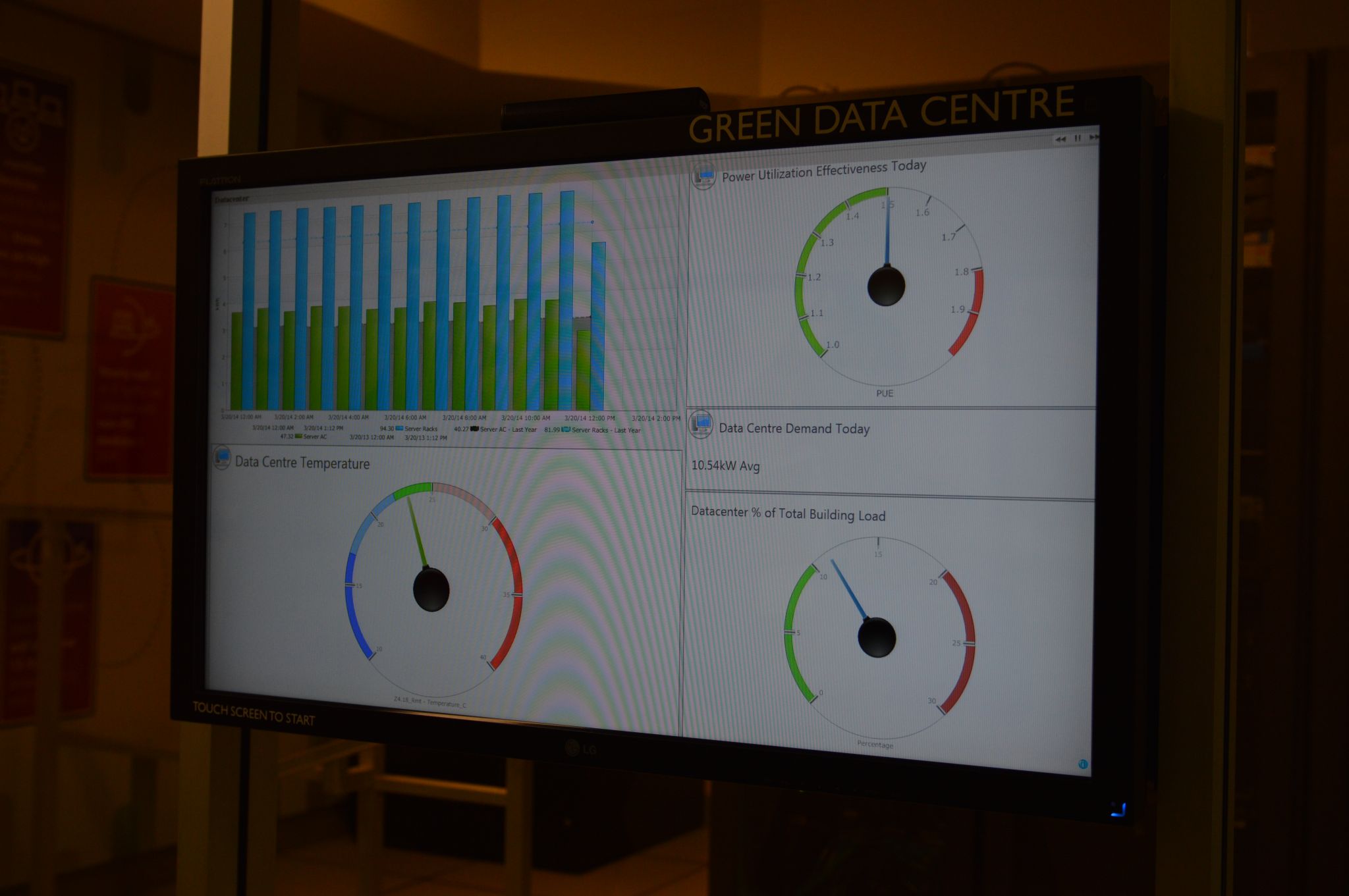

Earth Rangers’ information technology (IT) needs are similar to many of today’s connected businesses, and yet unique to their educational programming. All of Earth Rangers’ educational programs and content are developed onsite, from the kids’ and adult websites and social media content to the development of some of the public service announcements airing on national kids’ television and the production of videos used in school and community shows. This is in addition to the usual enterprise tools used to manage a modern organization. As a result, the ERC is home to a small 11.6-m2 (125-sf) data centre.

The data centre’s energy use has grown with the organization, now home to almost 90 virtual machines. Now fairly standard practice in data centres, virtualization allows many servers or computers to operate on fewer physical devices that run at higher capacity than standalone physical servers, saving energy, capital cost, and operational effort. Earth Rangers was an early adopter of virtualization in 2009. Despite this, since 2010, energy use in the ERC data centre more than doubled—a trend shared with buildings across the world.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates buildings accounted for over 35 per cent of total global energy use in 2010, and the amount of energy consumed annually by buildings is expected to grow by 50 per cent globally by 2050.5 There are large economic and environmental reasons to moderate these costs, and building owners are increasingly looking to technology to help mitigate and control energy costs as well as align with sustainability initiatives.

The dramatic adoption rate of technology is not limited in scope to buildings. It is happening in every sector of the economy, and a particularly noticeable trend is the emergence of the Internet of Everything (IoE), the connection of devices to each other, to people, and the Internet.

Practical examples include Nest internet-connected home thermostats, smartphone connected lights and security systems, security cameras that automatically detect license plates, electric cars that send an email if they’re unplugged before completely charging, and in-store retail signage that can send personalized promotions to your smart phone. The number of current examples is massive, and growing daily.

The IoE represents a $19 trillion opportunity globally between the private and public sectors over the next decade. Some of the main drivers of this value include:

- asset utilization ($2.5 trillion);

- employee productivity ($2.5 trillion);

- supply chain and logistics efficiencies ($2.7 trillion); and

- customer experience ($3.7 trillion).6

Smart buildings

‘Smart’ buildings, like ERC, make more intelligent use of space, create more productive places to work, require fewer resources to build, run, and manage—all while offering unique ways to provide tenants with an engaging experience in the space.

Asset utilization is a large cost-driver in the real estate industry; rent must be paid on a space whether in use or not. The “Workplace Utilization and Allocation Benchmark” study, conducted by United States General Services Administration (GSA), showcases multiple examples where large firms have realized major savings by using technology to reduce the amount of physical space required for their workforces, increasing utilization rates.

Mobile technology is enabling a reduction in the amount of office space allocated per occupant, saving space costs, while also increasing the productivity and reducing turnover from occupants who appreciate flexibility in where they work. Video conferencing can also help reduce travel expenses, without sacrificing face-to-face interaction between people. Collaboration technologies can make an office space more efficient by requiring less physical space, allowing employees to be more productive in flexible work environments. These benefits are easy to understand for those spending any amount of time commuting in a congested city.

Connected technology is making its way into more traditional building systems as well, and is not isolated to traditional information and communications technology (ICT) uses. Granular control of HVAC systems that also provide performance data, at little to no increase in capital cost, are now becoming widely available. Examples include:

- individually addressable lighting fixtures;

- Power-over -Ethernet (PoE) variable air volume (VAV) HVAC controls;

- parking management systems;

- PoE access controls; and

- digital signage.

These systems can all share a common network, reducing cabling costs and the capital cost to build a connected building to less than a traditionally built structure.

What does this all mean for the building? These previously disparate systems can now communicate with each other, offering improved tenant services and amenities, energy savings, corporate branding, easy integration of the collaboration technologies mentioned, and generally a modern office experience being demanded by tenants.

To make this more tangible, consider the following operations sequence that would be possible in a fully connected building:

After a short commute where your cell phone directs you along the least congested route, you arrive at the building, scan your access card and the parking management system directs you to an available electric car-charging station. After plugging in, you walk to the elevator and the automation system has already called the elevator, whisking you up to your floor without the need to interact with the system. Head down, reading e-mail on your smartphone, you are automatically connected to the building’s WiFi and recognized by the security camera at the entrance. Swiping your card to gain access to the office space, you choose a workstation for the day through a touchscreen interface. The lights come on because it is a cloudy morning, the ventilation system comes out of night mode, and you are logged onto the video phone on your chosen desk. You are the first to arrive, and so the coffee-maker now brews its first pot, anticipating further arrivals.

Walking to the printer, you pass by digital signage telling you how much energy the building is using today, how much your floor is using, and how that tracks against corporate goals. A weather feed tells you what to expect the rest of the day, and a transit feed informs you when the next train or bus arrives to take you to your next meeting up the street. You grab your printed reports and head to a video conference room. Walking into the room, a single touch starts a video meeting with a customer on the other side of the country.

Meanwhile, the facility operator sits at a remote location managing multiple buildings, seeing all these activities and managing the building much differently than previously possible. The operator can see, from individual meters, whether a toilet is running, if temperatures in a space are outside of prescribed limits, or if a belt has fallen off a fan. He can dispatch a service technician before you, the tenant, is even aware something needs to be fixed.

This is all possible in a connected building, and it is easy to imagine the thousands of variations that tenants and property managers will come up with to increase the value of their properties and control costs. All these sequences will require a robust network to handle the traffic, and building systems will need to communicate openly with each other, using protocols understood by each subsystem. The realization of this ideal space requires the network is leveraged by all systems, similarly to how these systems currently rely on electricity. The network is becoming a necessary utility.

However, system integration is not only for high-end new office towers. Implementation can be much simpler with a new build, but can be completed in existing buildings with a targeted strategic implementation plan. This can include capitalizing when systems require updates or reach obsolescence, new technology is deployed, or as tenant tastes and experience requirements change with leasing cycles. The Earth Rangers Centre has implemented some pieces of this puzzle through retrofitting, integrating lighting, security, HVAC, intrusion detection, and energy metering.

Connected building elements

Only occupied during regular business hours, ERC automatically arms its security system, shuts off unnecessary lights, and puts HVAC systems into night mode. This saves energy and also ensures a secure environment for staff and animal ambassadors, while providing an experience matching the organization’s values.

The market for smart and connected buildings is accelerating. Growing from $69 billion in 2012 to an expected $297 billion in 2022 at an annual rate of 16 per cent, this sector trails only consumer electronics in growth. Similarly, technology adoption is still happening at the Earth Rangers Centre as technologies offer new ways to reduce operational footprints and enable the business.

The ERC data centre was recently updated as existing servers and switches reached the end of their useful service lives. New servers have allowed for the deployment of thin clients—terminals that connect a monitor, keyboard, mouse, and phone to the data centre for more efficient central computing—that use less than half the energy of a laptop while being much easier to service and deploy by the IT department. Video conferencing and collaboration technology have also been added, with strategic connections between Earth Rangers and its supporters now being possible without travel and lost productivity. Future plans for remotely interacting with Earth Rangers members are also a possibility.

Conclusion

Future facility plans include a change in data centre cooling—taking advantage of colder winter air and the capacity of the ground-source heat pump system to halve the cooling requirements of the data centre—and deployment of software-based energy metering to track and control the energy being used by devices. IEA states the fastest growing segment of building energy use in many countries is from appliances and electronics. This mirrors what is happening at the Earth Rangers Centre, and the strategies mentioned here will mitigate those effects while allowing the organization to grow and innovate.

While certainly at the leading edge of smart building systems and technologies, the Earth Rangers Centre is not alone in adopting technology to enable it to grow and be more productive. Technology is enabling day-to-day business, while at the same time reducing the impact on the habitats and animals they are enabling kids’ to protect. Smart buildings are an opportunity for real estate everywhere, and will soon be the desire of tenants and facility managers across Canada.

Notes

1 For more information about the Earth Rangers Centre, see Andy Schonberger, P.Eng, MBA, LEED AP, and Scott Tarof, PhD’s article, “Building Heavy with the Earth Rangers” in the April 2012 issue of Construction Canada. (back to top)

2 For more on the Feed-in-Tariff program, see Gary Kassem’s article “Finding the Perfect FIT—Feed-in tariffs and long-term rooftop power generation commitments,” in the January 2011 issue of Construction Canada. (back to top)

3 For more information, see Real Property Association of Canada’s 2012 Energy Benchmarking Report at www.realpac.ca/?page=RPEBP5Reports. (back to top)

4 For more, see Greentech Media and Solar Energy Industry Association’s “U.S. Solar Market Insight” at www.greentechmedia.com/research/ussmi. (back to top)

5 See International Energy Agency’s Transition to Sustainable Buildings. (back to top)

6 For more, see “Embracing the Internet of Everything.” Visit www.cisco.com/web/about/ac79/docs/innov/IoE_Economy.pdf. (back to top)

Andy Schonberger, P.Eng, MBA, LEED AP, is the business development manager for Smart + Connected Communities at Cisco Canada. A mechanical engineer by training, he was director of the Earth Rangers Centre (ERC) for Sustainable Technology from 2010 to 2014. Schonberger chairs the Greater Toronto Chapter of the Canada Green Building Council (CaGBC) and holds a bachelor of energy management, mechanical engineering, from McMaster University, and an MBA in sustainability and strategy from York University. He can be reached at aschonbe@cisco.com.

Andy Schonberger, P.Eng, MBA, LEED AP, is the business development manager for Smart + Connected Communities at Cisco Canada. A mechanical engineer by training, he was director of the Earth Rangers Centre (ERC) for Sustainable Technology from 2010 to 2014. Schonberger chairs the Greater Toronto Chapter of the Canada Green Building Council (CaGBC) and holds a bachelor of energy management, mechanical engineering, from McMaster University, and an MBA in sustainability and strategy from York University. He can be reached at aschonbe@cisco.com.