The rebirth of ceiling fans

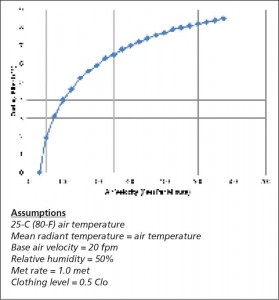

Image courtesy ASHRAE Thermal Comfort Tool

Energy savings

Research has been conducted on the best practices to avoid excessive stratification and provide occupant comfort for more than 30 years; these results are included in the ASHRAE Handbook:

In spite of this, engineers continue to design systems delivering low velocity, high temperature air at the ceiling. These designs are guaranteed to result in spaces that do not meet the minimum requirements of Standard 55-2004, and also fail to consider new ventilation requirements in Standard 62.1-2004.

This holds true for the 2010 versions of both ASHRAE 55 and 62.1, Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality. (See Daniel Int-Hout III’s article, “Overhead Heating,” in the March 2007 edition of ASHRAE Journal).

In the event air-conditioning is supplied to a facility, the fans are easily integrated into the mechanical system via a building automation system (BAS), operating as part of the HVAC, increasing the system effectiveness. By efficiently circulating the conditioned air, the fans reduce the need for ductwork, decreasing the system’s load.

In the cooler months, destratifying a space helps mix the air, resulting in more uniform temperatures. Savings accrue by slowly circulating heat trapped at the ceiling level down to the occupant/thermostat level before it is able to escape from the space. Even though the thermostat setpoint remains the same, the heating system does not have to work as hard to maintain the given setpoint. The energy savings achieved from reducing the amount of heat escaping through the roof is similar to turning the thermostat down 1.5 to 3 C (3 to 5 F).

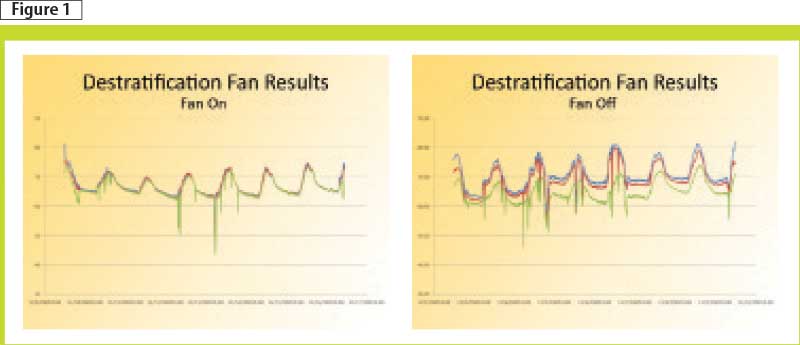

For example, a (20-ft) diameter fan was installed at (40 ft) in an airline hangar in Frankfort, Ky., where the average space temperature averaged 13 C (56 F). With the fans left on for a week, the space temperature became more uniform, drastically reducing temperature stratification (Figure 1).

Even small fans can play a role in efficiency efforts, homogenizing air within a space and cooling occupants. The most efficient ceiling fan certified by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Energy Star program employs a maximum of 30 W of electrical input power at its highest setting while providing smooth

(i.e. wobble-free), silent operation. (In Canada, Energy Star is a voluntary arrangement between Natural Resources Canada’s (NRCan’s) Office of Energy Efficiency (OEE) and organizations that manufacture, sell, or promote products meeting the U.S. program’s levels of energy performance). In comparison, a traditional fan in the same size category would run at 110 W.

Dealing with the clickity clack

No matter how attractive or effective a small ceiling fan is, annoying clicking and ticking will cause its appeal to wane. One misconception is all fans ultimately make this ticking noise, whether through excessive use or poor construction. Abandoning small, inefficient, alternating-current (AC) motors used in fans since the late 1890s, more sophisticated direct-current (DC) motors with sophisticated electronic controls are becoming the gold standard.

Images courtesy Big Ass Fans

Permanent magnetic movers, high-efficiency airfoils, and gearless drives have also been incorporated into large-diameter fans to meet today’s expectations for lasting silent operation. Additionally, onboard controls have eliminated excessive distance between the motor and the variable speed drive, preventing noise caused by electromagnetic or radio frequency interference.

With advanced technology and engineering, along with improved airfoil and motor designs, designers can now use ceilings fans in any building project, as illustrated by the two following case studies.

DPR Construction

Considering air naturally stratifies, HVAC systems must work overtime to maintain the temperature setpoint at the occupant/thermostat level. DPR Construction in San Diego, Calif., preempted this dilemma by designing a hybrid system with interconnected skylights that enables occupants to open or close the windows depending on temperature.

When interior and exterior temperatures reach equilibrium, the windows automatically open and the HVAC system turns off to help conserve energy. Taking it one step further, 10 large-diameter, low-speed fans (2.4 m [8 ft] each) were installed to enhance cross-ventilation by slowly moving large quantities of air in a non-disruptive fashion. The mechanical system takes its lead from the existing prevailing winds and the way in which the building is situated to help maximize the effects. According to DPR, this ventilation strategy is expected to reduce the number of operating hours of the HVAC system by 79 per cent in comparison to a sealed building.

Manitoba Hydro

Employee comfort was at the forefront of an ambitious construction project for the new 21-storey headquarters of Manitoba Hydro in Winnipeg. Instead of developing a return on investment (ROI) solely on the efficiency of the building, Manitoba Hydro took a different approach to feasibility involving human comfort as it relates to energy saved, explains Marc Pauls, an energy engineer with the company.

“Because our employee costs are roughly 100 times our utility bill, if we improve productivity and decrease absenteeism by one per cent each, that dwarfs any energy savings we would ever see,” he says.

Instead of recycling air, the 65,000-m2 (695,000-sf) building introduces 100 per cent fresh air year round, regardless of outside temperatures. During the colder months, the outside air is heated by a geothermal pump system in the floors; as a result, the hot air supplied by the heat pumps rises to the ceilings in the three atria.

At times, floor temperature remained 10 C (50 F) while the ceiling temperature settled at an uncomfortable 29 C (85 F). To eliminate this stratification, large-diameter, low-speed fans were installed in the 23-m (75-ft) high atria. With the fans running, the temperature discrepancy is now less than 2.8 C (5 F) within the space. Annually, the tower consumes 88 kWh/m², in comparison to 400 kWh/m² for a typical large-scale North American office tower in a more temperate climate.

Smaller Fans

Small fan motors often use alternating current (AC) to create the electromagnetic rotor poles needed to generate motor torque. This current changes polarity at 50/60 cycles per second, generating vibrations in the laminated steel motor core that propagate into the plastic or sheet metal fan housing and cause audible hum. As the motors age, the layers of stamped laminations loosen and vibrate against each other causing noise levels to increase.

Direct current (DC) motors, used in some large-diameter fans, eliminate this vibration by using permanent magnets to generate the rotor poles not requiring any AC current—this technique also reduces power consumption and leads to increased efficiency. Historically, due to the cost of control electronics, DC motors have been too expensive for most domestic fan applications but recent advances in power electronics and microprocessor controls are now allowing them to be competitive.

All in all, this author has found traditional ceiling fans generally utilized AC motors that can be extremely inefficient, generating a lot more energy than used to create mechanical shaft power and then releasing this excess energy as heat. The need to vent this heat drives the design of the motor and requires the large ventilated metal shrouds visible on nearly all conventional ceiling fans. These fans also break down over time as heat causes the laminated steel in their core to separate, leading to rattling and vibration.

Nina Wolgelenter is a senior writer for Big Ass Fan Co., a designer and manufacturer of large-diameter, low-speed ceiling and vertical fans in Lexington, Kentucky. She has a background in environmental education and journalism. Wolgelenter’s work on energy conservation, sustainability, and the impact of advanced fan technology has been published in magazines, newspapers, and online media outlets. She can be contacted via e-mail at nwolgelenter@bigassfans.com.