The need for energy performance targets

By Bob Marshall, P.Eng., BDS, LEED AP

When it comes to the energy efficiency of its buildings, Canada is something of a paradox. On one hand, the country has received its fair share of accolades for green initiatives. For example, this author was in France in September for an International Organization for Standardization (ISO) TC205/TC163 joint workshop, and received laurels for coming from the world’s only nation with a holistic building commissioning standard—Canadian Standards Association (CSA) Z320-11, Building Commissioning. On the other hand, the country recently ranked 11 out of 12 on the 2012 American Council for an Energy-efficient Economy (ACEEE) International Energy Efficiency Scorecard. (Many design/construction professionals find this ‘scorecard’ a little unfair. For example, in the building codes category, Canada is deemed to have no insulation, window, or HVAC requirements, unlike the United States. This author knows most provinces have similar [and far more stringent) requirements to those south of the border, so the overall rating is inaccurate. For more on this, read the Construction Canada Online article, “Canada Poor Performer in Energy Efficiency Study.” Visit www.constructioncanada.net/newsletters and search ‘ACEEE.’]).

Europe is often cited by North American sustainability experts as some sort of ‘Promised Land’ when it comes to energy-efficient design and green technologies. While there are indeed many glass towers on that side of the Atlantic, there are also higher-performance, energy-efficient building envelopes including vacuum-insulated panels (VIPs).

Photo courtesy Cedaridge Services Inc.

Further, the Europe Union (EU) is mandating near-zero-energy buildings (NZEBs)—a common term for the performance of a building based on the calculated or actual energy it consumes, including from renewable sources. This energy performance is ‘cost-optimized’ to the lowest amount during the estimated economic lifecycle. Public buildings must comply with the Directive 2010 of the European Parliament by the end of 2018; all new buildings must follow suit within the two years thereafter. As Europe’s definition of ‘cost-optimized’ takes into account installation, operating energy, and maintenance at the member (i.e. country level), NZEB can be implemented as part of holistic building commissioning in North America to improve efficiency in Canada and the United States.

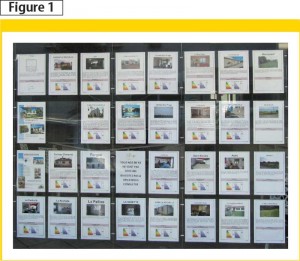

Image courtesy American Council for an Energy-efficient Economy

For existing buildings (accounting for more than 95 per cent of the European stock), prospective buyers and tenants are now required to be provided with an Energy Performance Certificate (calculated according to a standard methodology) as shown in Figure 1.

Canada (or the United States for that matter) does not yet have a standard or code requirement for energy performance certification, but National Research Council (NRC) and the Standards Council of Canada (SCC) are working on ‘energy performance targets’ and an ‘energy performance certificate standard,’ respectively.

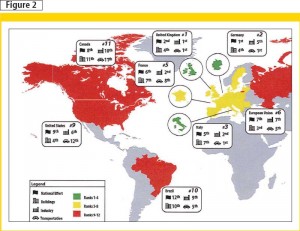

This article highlights the important work being done to raise Canada’s rank in ratings, shown in Figure 2, from red to green. The focus will be on the national codes and at the ISO level through SCC.

Image courtesy International Energy Agency

Importance of energy targets

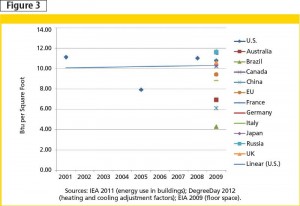

Canada has the highest energy use intensity (EUI), which continues to rise in residential buildings, as shown in Figure 3. (Regarding the disparity in this map, the United Kingdom currently has more than seven million third-party energy-certified buildings to British standards, compared to Canada, which has no certified buildings and an unpublished standard.)

According to Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), EUI is increased for high- and mid-rise apartments when compared to single-family houses (Figure 4). This is of concern given the growth of multi-unit residential towers in Canadian cities, along with the fact many of these newer buildings have inefficient glass walls with relatively poor building envelope durability.