The Language of R-values: Understanding differences between ‘nominal’ and ‘effective’

Thermal bridging

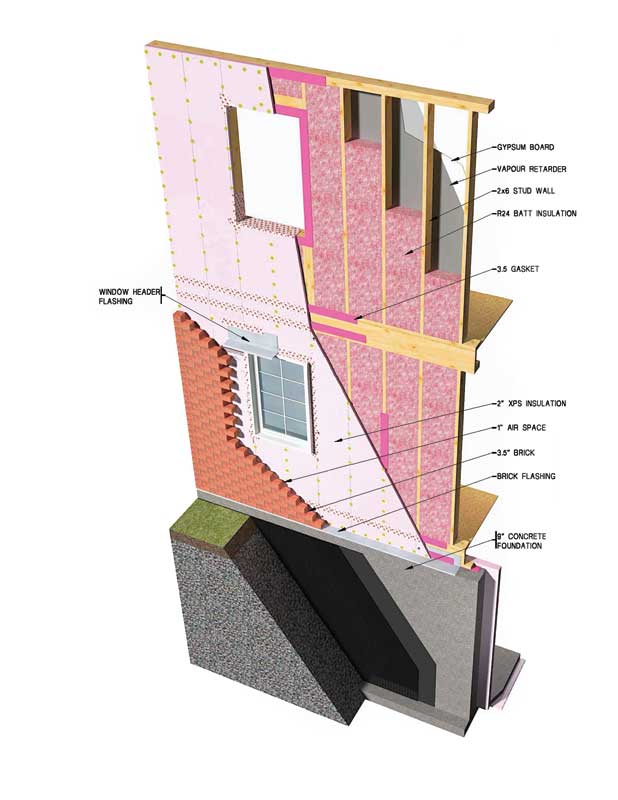

One of the main reasons the language has changed is due to thermal bridging. Thermal bridging occurs when a conductive material (i.e. a wood or steel stud) creates a path for heat flow to bypass the insulation layer. This shortcut significantly reduces the RSI value of the insulation layer, lowering the overall performance of the assembly. For example, a 2×6 at 406-mm (16-in.) on-centre (oc) wood stud wall with RSI 4.23 (R-24) batt insulation has an effective RSI value of 3.25—a 23 per cent loss of RSI value. Adjusting the assembly to steel studs further lowers the effective RSI value to 2.11—a 50 per cent loss.

One can try increasing insulation between the studs, but this has little effect on increasing RSI value as the main issue of thermal bridging through the studs has not been addressed. To minimize this loss, an insulated sheathing material needs to be placed on the exterior side of the framing members. When exterior insulated sheathings are installed, they reduce thermal bridging in assemblies by lessening the transfer of heat loss in winter and heat gain in summer, decreasing energy consumption.

The goal in moving to effective RSI values is to ensure a portion of the insulation is placed outside the framing members. The obvious advantage is lessening of heat loss. However, there are supplementary benefits. Placing insulation outside of the framing member allows the space between the studs to experience warmer temperatures.

This increase in temperature has a twofold effect on the durability of the assembly. First, it increases the temperature between the studs, which moves the dewpoint from its traditional location (i.e. back side of exterior sheathing) to the outer surface of the exterior sheathing. At this location, moisture can drain with the aid of a properly detailed rainscreen. This limits the amount of moisture that sensitive materials, such as wood or gypsum board, may encounter. Further, small amounts of moisture from condensation that may form on the coldest days of the year will normally dry up as a result of the increased temperatures provided by exterior insulated sheathings. This means moisture does not have a chance to deteriorate the assembly. This leads to the question: how much insulation is necessary outside of the framing members to reduce condensation in a cold climate such as Canada? It all depends on geographic area, but most locations will need RSI 1.76 to 2.64 (R-10 to R-15) to limit condensation formation in the assembly.

Exterior insulated sheathings provide more than just additional RSI value. Depending on the material properties, they can function as other barriers within the assembly. The code states any sheet or panel type material that has an air leakage characteristic less than 0.02 L/(s·m2) qualifies to be used as an air barrier or part of an air barrier system. If the exterior insulated sheathing meets that requirement, the air barrier can be moved from the interior (typically, sealed poly) to the exterior surface on the insulated sheathing. Moving the air barrier from the interior to the exterior reduces air leakage as complex details are transitioned to simple details. Basically, it is easier to air seal a building from the exterior than the interior as there are less penetrations and fewer transitions between different materials. This decrease in air leakage plays two roles. Firstly, it reduces moisture transferred via air leakage, which can be substantial depending on exterior/interior temperature and relative humidity (RH). Removal of this moisture from the assembly means durability is significantly increased. As the residential construction industry moves toward a stated goal of net-zero buildings, construction practices and techniques will need to be affordable. The first measure to ensure these buildings are affordable is to conserve energy before generating it.

To conserve energy, it is important to limit the amount of conditioned interior air leaked to the exterior. Not only will this reduce the cost of generating energy, but the occupants will also experience a comfortable building as air leakage has been minimized and controlled.

The last supplementary advantage is that exterior insulated sheathing can function as the weather barrier. If the sheathing is hydrophobic and has a continuous closed cell structure, that material can perform as the weather barrier, keeping in mind accessory items such as caulking and tape are required to seal any joint that is not ship-lapped (i.e. tongue and groove). This aids in the construction of net-zero buildings being affordable as exterior insulated sheathings can perform multiple functions resulting in lowering of total construction costs.