The importance of balanced ventilation

The NRC study also showed the overall air exchange rate in the house operated with balanced ventilation was up to 28 per cent greater than in the space with exhaust-only system. This improvement was realized regardless of whether the mode of the central air distribution system in the house was set to ‘off’ (no mixing) or ‘partial’ or ‘continuous’ mixing. With respect to the internal air distribution within the house, the ‘inter-zonal airflow’ was more in the house operated with balanced ventilation system than the one with an exhaust-only assembly, meaning there was a more even air exchange between the different rooms of the living space. This is another advantage of balanced ventilation.

These positive effects can translate into lower concentrations of the volatile organic indoor contaminants mentioned above.

The study also confirmed the increased energy efficiency of balanced ventilation when using an energy recovery ventilator. In the heating season of 2016-2017, the team recorded four to eight per cent less whole-house space heating energy consumption, which supports previous findings.

| MODES OF CENTRAL AIR DISTRIBUTION SYSTEMS |

|

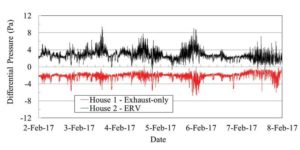

Two full-scale research houses were built side-by-side at the National Research Council Canada’s (NRC’s) Ottawa campus. One house was operated with exhaust-only ventilation, drawing air from the master bathroom, and the other operated with an energy recovery ventilator exhausting indoor air from the kitchen and bathrooms. The tests included the following central air distribution system scenarios. 1) Activation of central system (furnace) fan only when there is a need for heating or cooling. This means the central air distribution system would usually be off, resulting in no mixing during this period, the typical mode in homes. 2) Central air distribution system with continuous mixing, with the central system fan always on at low speed. The fan would switch to high speed if there is a need for heating or cooling. 3) Central air distribution system intermittently mixing supply air 20 per cent of the time. 4) Central furnace fan continuously ‘off.’ This mode was used to define a baseline, which was required for research purposes. |

Reducing contaminant transfer from attached garages into occupied spaces

Canadians appreciate having attached garages, and use them in many ways. According to Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), 61 per cent of Canadian dwellings have one. Unfortunately, homes with attached garages have up to three times higher indoor concentrations of the carcinogenic volatile compound benzene, when compared to homes without. This was found in many Canadian studies (for more information, read “Predictors of indoor air concentrations in smoking and non‐smoking residences” by M. Heroux, N. Clark, K.V. Ryswyk, et al; “Housing characteristics and indoor concentrations of selected volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in Québec City, Canada” by M. Héroux, D. Gauvin, N.L. Gilbert, et al; and “Predicting personal exposure of Windsor, Ontario residents to volatile organic compounds using indoor measurements and survey data” by C. Stocco, M. MacNeill, D. Wang D, et al). The origins of benzene are tanks of vehicles and other gas-powered equipment and gas storage cans. Due to this potential health hazard, Health Canada, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the European Commission recommend the reduction of residential benzene to as low levels as possible (consult “Predictors of indoor BTEX concentrations in Canadian residences” by A.J. Wheeler, S.L. Wong, C. Khoury, and J. Zhu J; “The Index Project: Critical Appraisal of the Setting and Implementation of Indoor Exposure Limits in the EU” by the Institute for Health and Consumer Protection, 2005; and Residential Indoor Air Quality Guideline, Science Assessment Document: Benzene by Health Canada).

Benzene finds its way from attached garages into living spaces through leaks in the shared walls and doors. This contaminant transfer is mainly driven by the pressure difference, if the pressure in the home is lower relative to the garage.

Two mitigation approaches have been found to be effective by NRC researchers. The first possibility is the installation of an exhaust fan in the attached garage, ensuring a negative pressure of 5 Pa relative to the living space. This means pollutants emitted in the attached garage are largely drawn outdoors, thus limiting the ingress of benzene into the occupied space. In a field study with occupied homes, it was demonstrated benzene intrusion into the studied homes could be reduced by 60 per cent. The second possibility is perfectly sealing the garage-home interface, which will also reduce benzene ingress into the home with the same efficiency (results will be published shortly by the NRC) (consult “Improved Sealing of Attached Garages Reduces Infiltration of Polluted Air into Adjoining Dwelling Spaces” by Daniel Aubin, Gary Mallach, Melissa St-Jean, Tim Shin, Keith Van Ryswyk, Ryan Kulka, Hongyou You, Don Fugler, Eric Lavigne, and Amanda Wheeler).

Measuring airflows

To support understanding of how air circulates through buildings, and in order to provide and refine science-based recommendations for ventilation, NRC researchers developed a Canadian analytical capacity called ‘multi-tracer gas method’ to help understand how pollutants move from adjacent zones like attached garages, attics, basements, or sub-slabs into living spaces. This analytical method is now available to exactly describe and quantify the amount and direction of airflow between these zones. Knowing the airflows will directly tell building professionals how the pollutants are moving into a facility. Pollutants mainly follow the airflow within a building—this translates into knowledge of how to design, improve, and adjust ventilation systems for a Canadian context.

The multi-tracer gas method (read “Tracer Gas Method,”), also called the perfluorocarbon tracer gases (PFT) method, uses PFTs—harmless volatile tracer gases—to mimic the movement of potentially harmful pollutants. These gases do not pose a threat to human health or the environment at the quantities emitted during the tests. This provides the opportunity to measure airflows in occupied buildings.