The art of specifying historical roof restoration

by Elaina Adams | January 1, 2012 8:50 am

[1]

[1]By Erika Huber

Historical buildings are central to Canada’s character and culture. Safeguarded at the federal, provincial, and municipal levels, these sites are granted special designations that dictate the manner in which they must be preserved and restored. In addition to the strong mandates of official heritage conservation, owners and interested parties often have a desire to preserve buildings’ historical integrity—both architecturally and esthetically.

Unfortunately, owners and other interested parties can have conflicting contemporary requirements for economical solutions, in addition to the need to use building materials that are sustainable, durable, and ‘green.’ Often, there is a conflict between the desires to preserve the past and to provide for the future. This divergence presents itself when specifiers need to choose roofing materials.

Due to their prominence in a building structure, roofs can be central to a building’s architectural character. On a practical level, of course, roofs are also essential to a building’s protection. A well-designed and installed roof shelters a historical building, potentially preserving it for decades. In contrast, misguided choices in roofing materials and applications accelerate a building’s deterioration.

Copper and zinc

When choosing replacement materials and applications, contemporary thinking often leads specifiers to these architectural metals for historical roofing. Copper enjoys a long history in world culture, due to its esthetic appeal and durability. Alchemists associated copper’s beautiful red-gold metal with Venus, and the first mirrors were made from this material. During excavations in Egypt, 5000-year-old copper mines were found to be still in operating condition. Together with gold, silver, and tin, it was one of the first metals to be worked by humanity about nine millennia ago. Ships built in the 15th century were covered in copper plates to protect them from algae infestation.

While copper is specified for many historical restoration and preservation projects throughout North America, pre-weathered zinc is often chosen for installations in which a visible weathering process is not desired. When the material combines with air and moisture, a matte blue-grey to blue-green surface is created, mimicking the historical application of terne metal. The material obtains a unique glow particularly well-suited for historic buildings.

[2]

[2]While both metals are finite resources, copper can be endlessly recycled without losing its properties—nearly all the copper ever mined is still in use today. Zinc is also highly recyclable, with 30 per cent produced today coming from recycled material. Recycling copper and zinc not only reduces landfill costs, but also reduces impact on the environment from original production.

The durability of copper and zinc is evidenced by roofing applications lasting more than 100 years. Roofs installed with these metals tend to be replaced due to obsolescence, and not due to corrosion or other damage effecting underlying construction. The patinas formed when copper ages serves as a natural protectant and barrier to corrosion. Natural zinc also forms a protective layer over time that blocks moisture and chemicals from penetrating to the zinc underneath. The longevity of copper and zinc roofing eliminates the need to use new roofing material and prevents waste.

According to sources quoted by the Canadian Copper and Brass Development Association (CCBDA), it has been estimated that, for an additional upfront cost of about two per cent to support green design, there is an average lifecycle savings of 20 per cent of total construction costs. Any higher initial expense for copper and zinc applications typically are offset by low to no maintenance costs over the building’s operational life.

Historical work

Despite the environmental and other advantages of using copper and zinc, specifiers are sometimes challenged in historical projects when these materials were not used on the original roof to be restored. When approaching the restoration or preservation of a historical structure, it is useful to follow the Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places, which is a pan-Canadian set of conservation principles and guidelines. While these standards provide specific guidelines for rehabilitation and restoration, they also outline a decision-making process that can help design professionals successfully specify roofing materials and applications different from the original assembly.

The first stage in the process is to understand the historical ‘place,’ which in part means to understand a structure’s heritage value. This consists not only of a building’s cultural, esthetic, and historical importance, but also its character-defining elements, forms, location, spatial configurations, uses, and cultural meanings. A modern sensitivity to conservation inspires and instructs interested parties to understand the original roofing material and application to preserve the original structure’s historical integrity.

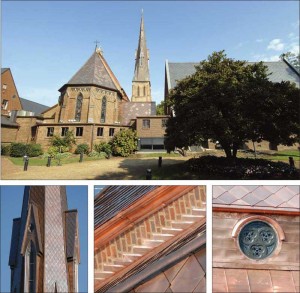

[3]

[3]Centre: Specifying the materials is only one step in historical preservation. Choosing craftsmen who understand quality installation is also key, as shown in the crafting of this step flashing.

Right: Custom-crafted in copper, the specialized architectural details like this eyebrow window can be exact replicas of the original.

Research into the roof’s history is an important and necessary element of this process. Sometimes, documentation and photographs exist, but more often a physical inspection of the roof is necessary. While wood, slate, and tile were all used in historical buildings, tin-plate iron, or tin roofing was used extensively in Canada in the 18th century. Often, however, research on a historical structure will be inconclusive. This means design professionals must either rely on the history of buildings in the general area, or specify solutions that mimic, but cannot re-create, the original roof material and application.

Specifiers who want to use an alternative to historical metal roofing materials often choose copper, which may or may not mimic the esthetic of the original, or galvanized zinc (which is closer to the look of tin-plated iron or terne metal, for example). In doing so, it is important to align the new application with the second stage in the decision-making process, which is to review the general standards for preservation, rehabilitation, and restoration set forth in Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places.

Focusing on preserving the structure’s “character-defining elements,” the general standards are helpful to a specifier. As already discussed, due to the important role the roof plays in the future integrity of a structure, and its prominence, the assemblies are often ‘character-defining.’ Consequently, it is important when choosing alternative roofing materials to stress alignment with the building’s original character by specifying alternative materials that match as closely as possible the scale, texture, and colouration of the historic roofing material.

Another important element of meeting the standards is to plan for appropriate and sustainable use. In the case of historical metal roofing, future maintenance will be a major issue in determining whether to use alternative materials. Most historical roofs have been replaced several times, and will need to be replaced again in the future. Therefore, preservation of “character-defining elements” must be weighed against the sustainability and durability of the roofing material and application, which play a big role in future maintenance and repair costs.

In specifying new materials or applications, it may be important to communicate to the owner the search for alternative roofing materials is not a new problem. Throughout the building’s history, for example, it may have been necessary to make changes to the original structure in order to properly preserve its heritage value and ensure its future.

Choosing between materials

Copper was chosen for the restoration of Toronto’s Old City Hall in the early 1990s. The original roof was clay-tiled, replaced in the early 1920s with a light-gauge copper to lower the expense associated with maintenance costs. While the light-gauge copper was much different from the clay tiles, the copper application was consistent with the building’s original character, and greatly reduced maintenance costs. The modern restoration continued the historical use of copper, but at a heavier gauge to extend the roof’s longevity.

[4]

[4]In order to install the heavier-gauge copper, an additional 13 mm (0.5 in.) of plywood was installed over the existing wood deck to support the heavier weight. Load calculations become an important part of determining the feasibility of using alternative roofing materials on historical buildings.

The high cost of historical restoration makes the longevity of a roof an important factor in choosing new materials. In North America, there are many structures that feature copper that has been in place for over 200 years. In Europe, copper roofs have been in service for more than three or four centuries.

High maintenance costs related to tin roofing, for example, do not make it a wise choice for modern preservation efforts. Tin roofing deteriorates when the coating fades and the iron rusts. Historically, undercoating of tin roofing—which may delay deterioration—was not used, and the surfaces may not have been consistently repainted. The most obvious choices for maintenance-free metal applications are copper and zinc; their value is realized by their longevity.

In addition to the material, it is important to be able to preserve the historical integrity of buildings through the use of similar installation techniques and craft practices (e.g. standing seam, rauten tile, and replacement of dormers and decorative elements). This practice is particularly challenging because the parties have to preserve the history while implementing more contemporary installation techniques. Historical craft practices may be too expensive to follow or have been superseded by modern improvements. In this regard, it is important to find modern craftsmen capable of reproducing historic details.

Cases in point

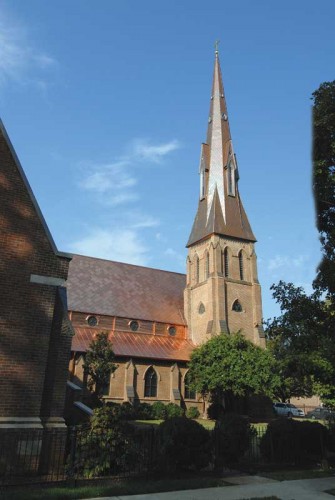

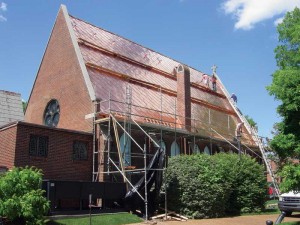

Two Huntsville, Ala., projects highlight the potential of using zinc and copper in historical roofing rejuvenation. The Episcopal Church of Nativity was built in the Gothic Revival style in 1859. A century and a half later, the church was faced with a deteriorating roof that threatened to damage the historical building. Efforts to determine the original roofing material specified by renowned architect Frank Wills were made, but little or no documentation was found. Additionally, several intervening repairs masked the original materials and the application.

Working within U.S. historical preservation guidelines, which are similar to those in Canada, the church was able to support the installation of a new copper rauten tile roof. Both the choice of metal, and the installation practice, were deemed acceptable alternatives to the suspected original (stamped terne metal) because the modern solution matched as closely as possible the scale, texture, and colouration of the historic roofing material.

The need for new roofing and rainwater systems can be challenging for specifiers working on historical projects. The roof of the Cooper House, one of the very few antebellum structures to survive the U.S. Civil War, was originally terne metal, painted grey—the same application that was popular throughout Canada in the 18th century. To maintain the house’s historical look, the architect chose a proprietary form of pre-weathered zinc for its historically correct grey colour, strength, and durability.

The architect designed a standing-seam roofing system with stainless steel ridge caps, and specified European-style gutter and seamless weld downspout. The historical society governing the site readily approved the application as consistent with the building’s historical architecture.

Conclusion

By carefully weighing the interests of all parties, and by following the decision-making process of Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places, specifiers can be successful in employing new and different roofing materials and applications to historic buildings. The key is to emphasize a compromise between the past and the future by finding a solution that values a structure’s history while ensuring its place in Canada’s cultural landscape for years to come.

Erika Huber has been affiliated with the architectural sheet metal industry since 1993, when her husband, Guenther, a Master Craftsman, founded CopperWorks Corp. (Decatur, Ala.). Currently the CFO of Ornamentals Manufacturing LLC, Huber supports both companies’ efforts to assist stakeholders in the use of architectural sheet metal in the historical restoration and preservation of buildings. She can be reached via e-mail at ehuber4404@charter.net.

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Nativity-1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/DSCN5659.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Nativity-images.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Copper-House.jpg

Source URL: https://www.constructioncanada.net/the-art-of-specifying-historical-roof-restoration/