Specifying the four roles of acoustic ceilings

by arslan_ahmed | November 10, 2023 4:00 pm

[1]

[1]By Gary Madaras, Ph.D.

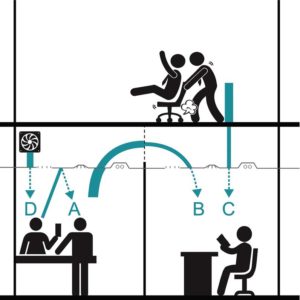

Suspended acoustic ceilings are mainstream inside many types of buildings and can serve multiple sound-related roles. They often are used primarily to add sound absorption high in the room where it is most effective (A in Figure 1). If the partitions between rooms do not extend full height, ceilings can be combined with lightweight plenum barriers to provide privacy from adjacent rooms on the same floor (B in Figure 1). Along with the floor slab, ceilings can provide sound isolation from rooms on the floor above (C in Figure 1). Lastly, suspended acoustic ceilings can be the only noise attenuation device between mechanical units in the plenum and occupants in the rooms below (D in Figure 1).

The designer and specifier decide which of these roles the ceiling will take in any project. The ceiling can assume all, none, or any combination of the four roles. It is possible for the partitions and floor slab to provide adequate isolation without a ceiling. Mechanical equipment can be located remotely to sound-sensitive rooms. Absorption can be provided on other surfaces and via furnishing. Therefore, it is important to establish if a ceiling will be implemented into the design and which roles it will take, so the other components of the building can be designed and specified appropriately.

[2]

[2]Prior to 2015, there was not a lot of information available to design and specification professionals on the performance of modular, suspended, acoustic panel ceiling systems inside commercial buildings, especially when they are combined with floor slabs, plenum barriers, light fixtures, and air distribution terminals and units. As a result, some designers and specifiers have had to rely on rules of thumb or misapply certain acoustic metrics to situations for which they were never intended. This article discusses systematically each potential role of acoustic ceilings, how ceilings work with other essential building components, and how specifiers can adjust their specifications for improved results. References to other articles written by the author will be provided for an expanded understanding of each topic.

First role: Room acoustics

Most occupied rooms and spaces require sound-absorptive surfaces to function properly. Adding absorption can make speech intelligible in learning spaces, create comfort by lowering occupant noise levels in restaurants, increase privacy in office workplaces, and improve patient outcomes by creating a quiet healing environment. The ceiling is the most effective surface for adding the required sound absorption because it is a no-contact surface and exposed to the sound field more than the floor and walls are.

The Canadian Standards Association (CSA Group) Z412 Office Ergonomics – An Application Standard for Workplace Ergonomics requires a minimum ceiling noise reduction coefficient (NRC) of 0.95 in unpartitioned open offices.1 ANSI/GBI 01-2019, otherwise known as Green Globes, requires minimum ceiling NRC of 0.90 in open offices, patient and eldercare areas, medication safety zones in healthcare facilities, and exam and treatment rooms in medical office buildings.2 The WELL Building Standard (WELL) by the International WELL Building Institute requires the ceilings over open workspaces and conferencing, learning, and dining spaces to be NRC 0.90.3 WELL claims that compliance with this high NRC criterion improves the functioning of the cardiovascular, endocrine, and nervous systems of the building’s occupants.

[3]

[3]An article titled “Specifying Ceiling Panels with High NRC”4 elaborates on the research supporting a connection between highly absorptive ceilings and improved human performance and health. More information about the building standards and guidelines that require high NRC ceilings is also provided.

Seeing the NRC 0.90 difference

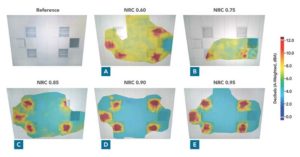

A sound intensity probe was used to scan acoustic ceiling systems ranging between NRC 0.60 and 0.95 while loud, broadband, noise was played through a loudspeaker in the space under them. A high-definition camera and analysis software tracked the probe’s location and the sound intensity levels it measured. These location-specific sound intensity data were then processed into colour sound maps, which were overlaid onto the digital image of the ceiling (Figure 2). The process allows visualization of ceiling NRC rating.

Yellow and red colours in Figure 2 indicate loud noise reflecting off the acoustic ceilings while blue indicates noise being absorbed. Red areas mostly are caused by noise reflecting off the hard, painted, metal air diffuser and light fixtures. Note the open return air grille on the right side of the images (blue) acts as an effective sound absorber because the noise passes through the opening into the plenum and is not reflected. The base question is, at what NRC rating does an acoustic ceiling stop behaving like a reflector (red and yellow) and behave more like an effective absorber (blue)? Based on the series of images in Figure 2 , the answer is NRC 0.90.

The perception of what constitutes high-performance sound absorption has slipped over time. Some specifiers have come to believe NRCs as low as 0.70 to 0.75 are acceptable, but as the sound intensity scans in Figure 2 show, at that level of performance, the ceiling is still acting more as a noise reflector than absorber.

Key takeaways: Room acoustics

[4]

[4]The primary role of the acoustic ceiling is to provide sound absorption above occupied rooms and spaces. Research has shown that human performance improves when the ceiling NRC is high (0.90). As a result, building design standards require or recommend high NRC ceilings. Specifications for normally occupied rooms should always include NRC ratings. Typically, NRC 0.90 is required for open spaces with multiple people and noise sources. Some standards do permit ceilings ratings of NRC 0.80 in enclosed rooms where people gather for communication, such as classrooms, conference rooms, and training rooms. Some standards also permit NRC ceiling ratings as low as 0.70-0.75 in small private rooms where there is typically one person and no loud noise sources.

Second role: Privacy between rooms

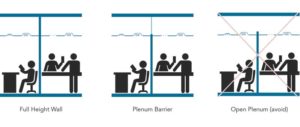

Sound isolation between rooms can be important for speech privacy or limiting noise transmission to avoid annoyance or distraction. Achieving sound isolation between rooms relates to the construction of the overall envelopes of the rooms including the walls, floors, windows, doors, and sometimes, the ceilings. Figure 3 shows three different sound isolation approaches. The overall level of sound isolation often depends on the weakest link in the room’s boundary construction.

Acoustics requirements in building standards utilize sound transmission class (STC) most frequently as the sound isolation performance metric. STC requirements generally range from 40 to 50, with STC 45 being the most common.5 Technically, for a partition to have a STC rating, it is required to be full-height from the structural floor slab to the structural floor slab or roof. The CSA Group’s Z8000 standard, Canadian Healthcare Facilities, requires full-height wall construction between any rooms with partition STC ratings of 45 or higher, including administrative offices, inpatient bedrooms, treatment rooms, and meeting and seminar rooms (refer to paragraph 12.2.7.2.10).

When the partition instead stops at ceiling level, some standards such as GCworkplace Fit-up Standards by Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) require the acoustic ceiling to be combined with a lightweight plenum barrier positioned vertically over the partition. When this is the design approach, the combined Ceiling Attenuation Class (CAC) rating of the ceiling and the plenum barrier tested together needs to equal the STC rating of the partition below the ceiling. Building design standards do not permit open/common plenums above ceilings because the noise can too easily pass between rooms.

The specified slider does not exist.

When the partitions are not constructed full height, noise can leak easily through the penetrations in the ceiling system for recessed light fixtures, air supply diffusers, return air grilles, and other ceiling-mounted devices. These noise leaks can decrease the ceiling system performance up to 10 CAC points. More importantly, it is not a uniform 10 decibel (dB) decrease across all frequencies. High frequency sound with small wavelengths, which makes speech more recognizable and intelligible, passes more easily through these leaks in the ceiling than low frequency sound. High frequency degradation to the ceiling performance is 15-20+ dB, making speech from the adjacent room four times louder. For a thorough discussion about how penetrations degrade ceiling system sound isolation performance, including colour sound maps showing the noise leaks, refer to an article written by the author titled “Plenum Barriers, Speech Privacy, and Workplace 2.0 Fit-up Standards.”6

Plenum barriers

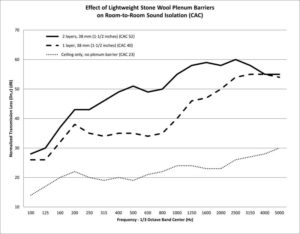

Lightweight plenum barriers can be constructed of a variety of different materials. For reasons discussed in the article referenced above, this article focuses on stone wool plenum barriers due to their low cost, relatively quick installation, pliability, and high sound isolation performance (Figure 4).

Figure 5 shows the sound isolation performance differences in terms of frequency-specific transmission loss (TL) and wideband STC rating for an acoustic ceiling alone, compared to stone wool plenum barriers. A standard acoustic ceiling alone, regardless of the material, weight, and NRC/CAC ratings, cannot achieve the required 40-50 level of performance, especially when the unavoidable penetrations are considered. It is not until a plenum barrier is added that the room-to-room isolation reaches that level. A stone wool ceiling with a single-layer, stone wool, plenum barrier reaches the CAC 40 level of performance. When a second layer is added with an interstitial airspace, the performance increases to more than CAC 50. Additional information about plenum barriers of different material types and their performance levels is available in the author’s article cited in this section.6

[5]

[5]Key takeaways: Privacy between rooms

The relevance of the acoustic ceiling to sound isolation between rooms on the same floor is dependent on the construction of the partitions. If the partitions are full height, then the acoustic ceiling plays no role. The portion of the partition above the ceiling is providing the same sound isolation as the part below the ceiling. The sound isolation will be the same whether or not the acoustic ceiling is present. Therefore, the CAC rating of the ceiling panel is irrelevant and does not need to be included in the ceiling panel specification. Since ceiling panels with moderate to high CAC ratings typically have lower NRC ratings, including the CAC rating in the specification can instead result in noncompliance with required absorption performance unless additional absorption is added to the floor or walls.

[6]

[6]However, if the partition is not full-height and privacy is expected between normally occupied rooms, then a plenum barrier should be combined with the acoustic ceiling to comply with the sound isolation requirement in the standards and with general user expectations. This is the only instance where a CAC rating should be specified. It should be the combined ceiling/plenum barrier rating and should equal the STC rating of the partition construction below the ceiling.

Third role: Isolation from floors above

Sound isolation is also important between vertically adjacent rooms. Students being energetic in their classroom on an upper floor of a school building should not disturb peers concentrating in the library below. In these cases, the floor construction is the primary building element controlling the amount of noise transmitting between rooms. In buildings with ceilings, it is the combination of the floor and ceiling assembly that establishes the overall noise isolation performance between rooms.

Guidelines by the Facilities Guidelines Institute (FGI) for the design and construction of healthcare facilities require floor-ceiling assemblies between inpatient rooms in hospitals achieve a minimum STC 50 rating. Another standard with the STC 50 requirement for floor-ceiling assemblies is the American National Standards Institute/Acoustical Society of America (ANSI/ASA) S12.60, Acoustical Performance Criteria, Design Requirements, and Guidelines for Schools – Part 1 Permanent Schools (2020).

[7]Ideally, there would be accessible, STC reports for various floor-ceiling assemblies made of concrete slabs on metal decks with acoustic ceilings suspended below. Until 2021, those tests were difficult to find. Instead, when floor-to-floor sound isolation is important on a project, a common practice amongst some architects, specifiers, and acousticians is to specify an acoustic ceiling panel that has a minimum weight of 4.88 kg/m2 (1 psf) or a CAC rating of 35. The thought is the extra weight, compared to, for example, a panel that only weighs 2.44 kg/m2 (0.50 psf), will result in a higher assembly STC rating, or a ceiling panel with a CAC rating of 35 will result in a higher STC rating than a panel with a CAC rating of 25.

[7]Ideally, there would be accessible, STC reports for various floor-ceiling assemblies made of concrete slabs on metal decks with acoustic ceilings suspended below. Until 2021, those tests were difficult to find. Instead, when floor-to-floor sound isolation is important on a project, a common practice amongst some architects, specifiers, and acousticians is to specify an acoustic ceiling panel that has a minimum weight of 4.88 kg/m2 (1 psf) or a CAC rating of 35. The thought is the extra weight, compared to, for example, a panel that only weighs 2.44 kg/m2 (0.50 psf), will result in a higher assembly STC rating, or a ceiling panel with a CAC rating of 35 will result in a higher STC rating than a panel with a CAC rating of 25.

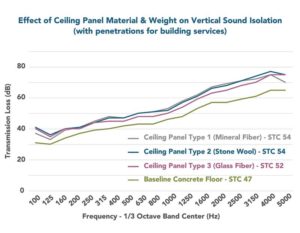

In 2021, a conclusive study was conducted by the author to determine if the weight or CAC rating of the ceiling panel influenced the assembly STC rating. The findings were published in an article titled “Effects of Acoustical Ceilings on Vertical Sound Isolation.”7 The experiment compared the frequency-specific TL and wideband STC rating for a baseline concrete floor slab on metal structural deck with vinyl composite tile finish floor, versus the same baseline floor with a variety of acoustic ceiling systems suspended below.

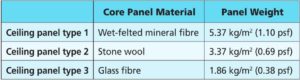

Three different types of acoustic ceiling panels were tested. All ceiling panels were the same size and thickness with similar painted white finishes and square, lay-in edges. The main differences between the ceiling panel types were the core material types, panel weights, and acoustic performances.

The CAC ratings of the ceiling panels ranged from 20 to 35, representing the most common performance range used in the industry. The NRC ratings of the ceiling panels ranged from 0.75 to 0.95. The experiment was first conducted without recessed light fixtures and air distribution devices in the ceiling systems and then again with them. The presence or absence of the penetrations for lights and air distribution had an insignificant effect on the STC ratings of the different floor-ceiling assemblies.

Figure 6 shows the baseline concrete floor without a ceiling achieved STC 47, three points below the STC 50 rating that some standards set as minimum. When added below the floor slab, each of the ceilings increased the assembly STC rating to above the STC 50 minimum. In addition, all the ceilings increased the STC rating a similar amount. With two of the ceilings (stone wool and mineral fibre), the assembly had the same STC rating of 54 and the frequency-specific TL performance overlapped. The third ceiling panel (fibreglass) resulted in a slightly lower STC rating of 52, but still some of the frequency-specific TL values overlapped with the other ceiling types. Given the variation inherent in the test method (1.5 to 4 dB), one cannot conclude fibreglass panels performed differently than the stone wool or mineral fibre panels.

Key takeaways: Isolation from floors above

Adding an acoustic ceiling below a floor slab increases the assembly STC rating approximately six points. This improvement is substantial because without it, the floor slab would need to be more massive to reach the STC 50 minimum, and the resulting impact on the building structure and foundation could be costly for the project. Instead, a moderate weight concrete floor slab with an acoustic ceiling below can meet the STC 50 minimum requirements in building standards. Most importantly, the material type, weight, and CAC rating of the ceiling does not have a significant effect on the overall assembly STC rating. Specifiers can omit CAC rating from the specification and be confident the slight difference in the panel weight (typically less the 2.44 kg/m2 or 0.5 psf) is not substantial enough to affect the STC rating of the assembly. Caution should be taken if the floor or ceiling panels are significantly lower in weight than those used in the author’s 2021 study.

Role four: Achieve background noise levels

Designing a building and its systems to achieve acceptable background noise levels inside rooms is important and required by most building standards.5 If background sound is too loud, it interferes with speech intelligibility and causes stress and discomfort. If it is too quiet, every little noise can be disruptive and privacy suffers. Once noise is inside a room, its negative impact can be lessened by a high NRC ceiling system. Instead of reflecting off all the room surfaces repeatedly, amplifying itself, much of the energy is absorbed by the acoustic ceiling. Beyond this general benefit, acoustic ceilings are typically the only attenuation device between a noisy piece of mechanical equipment in the plenum and people in the room below.

[8]

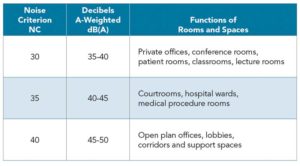

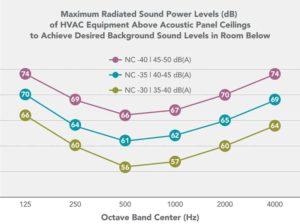

[8]Noisy mechanical equipment should be located away from sound sensitive rooms. Placing a fan-powered box over a corridor is better than positioning it directly over the students inside a classroom. There are situations though when placing noisy equipment over a sound-sensitive room is unavoidable. When this is the case, a simple and straightforward method of ensuring the suspended acoustic ceiling has the capability of attenuating the plenum noise is laid out in the Air-Conditioning Heating and Refrigeration Institute’s (AHRI) Standard 885 (2008), Procedure for Estimating Occupied Space Sound Levels in the Application of Air Terminals and Air Outlets8 as well as in the ASHRAE Handbook HVAC Applications (2023).9 Begin by selecting the appropriate background sound level for each room. Figure 7 provides example background sound levels for many room types in two formats; noise criterion (NC) ratings and A-weighted decibels (dBA) from the ASHRAE Handbook.

Next, the amount of attenuation an acoustic ceiling system can provide needs to be considered. Some building professionals may not be aware of the mechanical noise attenuation prediction method defined in the ASHRAE Handbook and AHRI standard. Many have instead strayed toward a rule-of-thumb based on ceiling panel material type, such as mineral fibre; a certain minimum weight, such as 4.88 kg/m2 (1.0 psf); or a certain sound isolation metric, such as a minimum CAC rating of 35. None of these are correct, and to understand why, one must first understand how acoustic ceilings attenuate plenum noise.

Based on ASHRAE research,11 an acoustic ceiling attenuates the noise of mechanical equipment based on three factors: high absorption (NRC) limits noise inside the plenum and inside the room, a malleable panel surface seals noise leaks where the ceiling panels rest on the metal grid flanges, and moderate panel weight limits the sound passing straight through the panel. The key ASHRAE finding is that most standard ceiling panels available in the market perform the same in the frequencies of concern (500 Hertz octave band and below). Some panels have more weight, but they do not provide as much absorption. Other panels are softer and seal leaks along the grid better, but allow more sound to pass through. When studied empirically, researchers found the various ceiling panels performed within one to four dB of each other. A difference of three dB is barely perceptible. An important outcome of this research is that no metric such as NRC, CAC, or STC is required to characterize the performance of different ceiling panels because they perform so similarly.

An article titled “Specifying Ceilings and HVAC Equipment to Meet Acoustic Requirements” discusses the original ASHRAE research and how the findings were used to develop the industry-consensus prediction method.12

[9]

[9]Prediction method

After establishing the goal background sound levels for each room and understanding that most ceiling panels provide the same amount of sound attenuation, one can focus on the key variables, the location, and sound power levels of the mechanical unit itself.

When possible, locate HVAC equipment over unoccupied or noisy areas such as corridors, storage rooms, and lobbies. Avoid locating HVAC equipment over normally occupied rooms with background noise requirements of NC-35 / 40-45 dB(A) or lower. When locating HVAC equipment over occupied rooms cannot be avoided, use Figure 8 to determine the maximum sound power levels for the HVAC equipment in the plenum. Specify the appropriate device model, configuration, operating conditions, and maximum sound power levels so the values in Figure 8 are not exceeded.

Key takeaways: Achieve background noise levels

The ceiling’s role in achieving acceptable background noise levels by attenuating mechanical equipment noise in the plenum can be important. Most ceiling panels perform the same. The method of starting with the mechanical unit’s sound power levels and then trying to specify a particular ceiling panel material, weight, or CAC rating is inconsistent with the industry-consensus prediction method in AHRI Standard 885 and the ASHRAE Handbook. Therefore, the CAC rating should not be included in the specification. Instead, start with the goal background sound levels for the room, add the attenuation provided by most acoustic ceiling panels per Figure 8, and specify the maximum permissible, octave band, sound power levels in the specification section for mechanical devices.

Final thoughts

While an acoustic ceiling can serve multiple roles, its primary one is to absorb sound. To ensure good room acoustics and to comply with building design standards, a minimum ceiling NRC of 0.90 should be specified in open or larger spaces with multiple occupants and noise sources.

On some projects, the acoustic ceiling may need to take on acoustic roles beyond absorption. If the interior partitions are not full-height and the acoustic ceiling’s role is expanded to include horizontal sound isolation, the ceiling alone cannot achieve high enough privacy between rooms, especially when the noise leaks caused by the penetrations for lights and air distribution devices are considered. To comply with the STC 40, 45, and 50 levels of sound isolation requirements in the standards, a lightweight plenum barrier working in combination with the acoustic ceiling is the optimal design approach. This is the only application where the CAC rating of the ceiling system and plenum barrier combined should be specified, and the value should match the STC rating of the partition.

When the acoustic ceiling must work with the floor slab to take on the role of floor-to-floor sound isolation, it will increase the STC rating approximately six points beyond that of the floor slab alone. The type of ceiling panel material and its weight are not significant factors. The CAC rating is irrelevant to this application and should not be specified. Instead, a floor slab with an STC rating of no more than six points lower than that required by the standard should be specified.

Lastly, when the acoustic ceiling needs to take on the role of mechanical noise attenuation, most standard ceiling panels perform the same in the frequencies of concern. CAC and STC rating are irrelevant and ASHRAE warns against using these metrics as the prediction method. Instead, utilize the prediction method in either AHRI Standard 885 or the ASHRAE Handbook. Begin with the goal background noise levels. Add the attenuation provided by an acoustic ceiling. Specify the maximum permissible sound power levels of the mechanical units in the plenum.

Notes

1 Refer to Table B.4 Design Recommendations for Open Offices – Unpartitioned on page 105 of the 2017 version.

2 Refer to section 11.5.4 Reverberation Time or Ceiling Noise Reduction Coefficient (NRC) in ANSI/GBI 01-2019 Green Globes Assessment Protocol for Commercial Buildings.

3 Refer to the Sound Concept, feature S05 Sound Reducing Services of version 2 of the WELL Building Standard. The rating is for tier two performance and credits.

4 For more information refer to The Construction Specifier, “Specifying ceiling panels with a high NRC[10];” Gary Madaras, PhD; Feb. 21, 2020.

5 For more information refer to Acoustical Interior Construction, “A Guide on the Four Categories for Acoustics Criteria in Building Standards and Guidelines[11];” Gary Madaras, PhD; July-September 2016, pgs. 27-29. CISCA has granted permission for the article to be available gratis online.

6 For more information refer to Construction Canada, “Plenum barriers, speech privacy and workplace 2.0 fit-up standards[12];” Gary Madaras, PhD; September 21, 2017.

7 For more information refer to Construction Canada, “Effects of acoustic ceilings on vertical sound isolation[13];” Gary Madaras, PhD; November 5, 2021.

8 Refer to AHRI Standard 885 (2008), “Procedure for Estimating Occupied Space Sound Levels in the Application of Air Terminals and Air Outlets.” Refer to Appendix D Sound Path Factors, Sections D1.6 Ceiling/Space Effect, Table D14 Uncorrected Ceiling/Space Effect Attenuation Values and Table D15 Ceiling/Space Effect Examples.

9 Refer to the ASHRAE Handbook HVAC Applications (2019), Chapter 49 Noise and Vibration Control, Section 2.8, subsection Sound Transmission Through Ceilings and Table 43 Ceiling/Plenum/Room Attenuation in dB for Generic Ceiling in T-Bar Suspension Systems.

10 The background noise requirements provided in Figure 7 are from the ASHRAE Handbook, HVAC Application (2019), Table 1 Design Guidelines for HVAC-Related Background Sound in Rooms. If the building must comply with a different building standard or guideline, use those values instead.

11 Refer to ASHRAE research project RP-755, “Sound transmission through ceilings from air terminal devices in the plenum: final report,” conducted by the National Research Council Canada, A.C.C. Warnock, January 1997.

12 For more information refer to Construction Canada, “Specifying acoustic ceilings and HVAC equipment to meet acoustic requirements[14];” Gary Madaras, PhD; November 4, 2022.

13 The values in this graph were derived using the method in the 2019 ASHRAE Handbook HVAC Applications and 2008 AHRI Standard 885. Octave band values for the Noise Criterion curves taken from Table 13 in AHRI Standard 885 were added to the ‘Environmental Adjustment Factor’ in Table C1 in AHRI Standard 885. The average “Uncorrected Ceiling/Space Effect Attenuation Values” per Table D14 in AHRI Standard 885 were added to the sum to get the maximum permissible sound power levels for the mechanical equipment in the plenum.

[15]Author

[15]Author

Gary Madaras, Ph.D., is an acoustics specialist at Rockfon. He helps designers and specifiers learn the optimized acoustics design approach and apply it correctly to their projects. He is a member of the Acoustical Society of America (ASA), the Canadian Acoustical Association (CAA), and the Institute of Noise Control Engineering (INCE). Madaras can be reached at gary.madaras@rockfon.com.

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Photo4_Rockfon_ON-ROCKWOOL_BochslerCreative-5158.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Figure1_Rockfon-GMadaras.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Figure2_Rockfon-GMadaras.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Figure3_Rockfon-GMadaras.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Figure5_Rockfon-GMadaras.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Figure6_Rockfon-GMadaras.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/table-for-ceiling-panel-types-materials-adn-weights.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Figure7_Rockfon-GMadaras.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Figure8_Rockfon-GMadaras.jpg

- Specifying ceiling panels with a high NRC: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/specifying-ceiling-panels-with-a-high-nrc/

- A Guide on the Four Categories for Acoustics Criteria in Building Standards and Guidelines: https://www.rockfon.com/siteassets/rockfon-na/articles/rockfon-acoustical-interior-construction-building-standards-and-guidelines-garymadaras-summer-2016-article.pdf

- Plenum barriers, speech privacy and workplace 2.0 fit-up standards: https://www.constructioncanada.net/plenum-barriers-speech-privacy-workplace-2-0-fit-standards/

- Effects of acoustic ceilings on vertical sound isolation: https://www.constructioncanada.net/effects-of-acoustical-ceilings-on-vertical-sound-isolation/4/

- Specifying acoustic ceilings and HVAC equipment to meet acoustic requirements: https://www.constructioncanada.net/specifying-ceilings-and-hvac-equipment-to-meet-acoustic-requirements/4/

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Madaras_Headshot-f.jpg

Source URL: https://www.constructioncanada.net/specifying-the-four-roles-of-acoustic-ceilings/