Specifying recycled concrete aggregate

By Uwe Schutz, PhD, and R. Doug Hooton, PhD, P.Eng.

In seemingly every sector, from government to real estate development to retail, project owners are looking to make their construction sites greener. The movement toward more sustainable construction practices is neither trend nor fad; it is a functional philosophy responding to both a heightened public consciousness of the impact of human activities on the planet and the added value of doing ‘the right thing.’

The use of recycled or reclaimed materials is one of the ways builders and specifiers are achieving a stronger sustainability scorecard for their projects. One such example, recycled concrete aggregate (RCA), is gaining significant traction in several European countries and in Japan. Now, demand is also on the rise in Canada and the United States.

The global growth in interest and use of this material can be attributed to its considerable environmental and practical advantages. This article examines RCA and its impact on various construction projects and sitework.

Aggregate 101

Aggregate is found in many types of structures and building projects, including roads, bridges, buildings, and dams. It is mostly used for concrete, asphalt pavement, and road bases, but other applications include ornamental landscaping, erosion control, and manufactured concrete products (e.g. brick, block, paving stone, pipe, and tunnel liners). Further, aggregate is employed in:

- water purification;

- sandpaper;

- crayons;

- plastics;

- chewing gum;

- paper;

- sugar;

- rubber;

- fertilizers;

- glass; and

- ceramics.

In concrete, virgin aggregate (e.g. sand, gravel, crushed stone, and lightweight aggregate) occupies approximately 60 to 75 per cent of the volume. This aggregate needs to be clean, and free of absorbed chemicals or coatings of clay or other fine materials that could cause concrete deterioration. Aggregate properties such as gradation, maximum size, unit weight, particle shape, surface texture, and moisture content (MC) significantly impact workability and pumpability of plastic concrete, as well as its durability, strength, thermal properties, and density once hardened.

Virgin aggregate has to be mined from surface deposits of sand and gravel or by blasting and crushing rock in quarries. As urban areas expand, it is more difficult to obtain permits for new pits and quarries, requiring aggregate to be transported from increasing distances.

What is recycled concrete aggregate?

There are three main categories of RCA that are either used as aggregate in new concrete or as granular base material. (This definition comes from the Ontario Ministry of Transportation (MTO) Materials Engineering and Research Office’s “Supporting the Thematic Strategy on Waste Prevention and Recycling Service Request Five Under Contract Env.G.4/Fra/2008/011225,” released in October 2010).

Construction and demolition waste (CDW)

CDW consists of materials arising from activities such as the construction or demolition of buildings and civil infrastructure, road planing, and maintenance. Examples of CDW include:

- metals;

- glass;

- solvents;

- gypsum;

- brick;

- wood; and

- concrete, which may or may not be contaminated with small amounts of other demolition materials.

Reclaimed concrete material (RCM)

RCM is a generic term for after-use, hardened, hydraulic-cement concrete that has been obtained from variable sources (e.g. sidewalks and concrete roads) for use as a construction material.

Returned crushed concrete (RCC)

Returned crushed concrete (RCC)

RCC is unused concrete material obtained from plastic concrete that has been returned directly to the ready-mixed concrete plant, allowed to harden, and processed by crushing. It can be used for the same applications as CDW and RCM, but since it has never left the mixing truck, it is cleaner and it has a well-known origin—thus, it is more readily accepted for use in fresh concrete.

The pluses and minuses of RCA

Recycled concrete aggregate is a viable choice for various applications and offers numerous environmental and efficiency benefits. As with any material, the maximum benefit is obtained only when it is used for the right applications.

Advantage #1: availability

Arguably the single biggest edge of RCA compared to virgin aggregate is its availability and proximity to virtually any market. Construction demolition is prevalent in all major urban centres, ensuring a supply of readily accessible material. If a structure is deconstructed and the resulting CDW is used for suitable applications onsite, the owner reduces the need to purchase and transport virgin aggregate while also saving the hauling, dumping, and landfill costs for these materials.

In Canada, there were more than 3.3 million tonnes of CDW generated in 2002. (This comes from the 2005 Statistics Canada report, Human Activity and the Environment). In 2010, the United States generated 104 million tonnes, while Europe generated more than 500 tonnes in 2009–2010. (For more information, visit www.wastebusinessjournal.com/news/wbj20101005A.htm and www.biois.com/en/menu-en/expertise-en/assess/new-a/construction-waste-management-in-europe.html). (These numbers cover all materials falling under the CDW classification, including concrete.)

Advantage #2: smaller environmental and social footprint

The most obvious environmental benefit of specifying RCA is it proportionally reduces the amount of virgin aggregate that must be mined. This is no small consideration and it will likely become an even more significant factor going forward as social and environmental concerns rise over developing new quarries, while aggregate reserves are on the decline.

In Ontario, for example, future aggregate requirements have been estimated at 186 million tonnes annually for the next 20 years—a 13 per cent increase compared to the past. The licensing of replacement aggregate reserves has not kept pace with this growing demand, and this gap will result in a 2.5:1 consumption replacement ratio between 1991 and 2013 alone.

In addition to the benefits in terms of efficiency and economics, the close-to-market availability of recycled concrete aggregate also offers environmental and social advantages. Proximity to most project sites conceivably precludes transportation of thousands of truckloads of materials on local roads and highways. The implications of this traffic decrease include:

- less congestion (and wear and tear) on roadways;

- reduced traffic noise;

- less dust related to the passage of trucks on gravel service roads from quarries; and

- lower carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions related to transportation.

Again, the proof is in the numbers—an average ready-mix plant annually uses about 150,000 tonnes of aggregate, requiring delivery from nearly 4000 trucks every year.

Specifying RCA on a project does more than just give a new life to old concrete; it also keeps it out of the wastestream. The environmental impact is considerable—2.8 million tonnes of CDW were landfilled in Canada in 2002.

Advantage #3: LEED potential

To demonstrate a commitment to sustainability, a growing number of private-sector owners and government organizations are aiming for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification of their construction projects.

LEED particularly rewards the reduction of waste at a product’s source. The use of RCA can help earn the following credits:

- Materials and Resources (MR) Credit 2, Construction Waste Management;

- MR Credit 4, Recycled Content; and

- MR Credit 5, Regional Materials.

Technical challenges

While RCA is a versatile alternative to virgin aggregate, it is not without its challenges and special requirements. It is perfect for use in road base applications; but it should not be employed for architectural concrete due to potential discrepancies in the final material’s surface colour.

In the case of RCM/CDW, the chemical and physical properties vary more when compared to natural aggregate depending on the amount of attached mortar, or exposure of the concrete to foreign materials and chemicals during its lifecycle, processing, and storage.

When used to replace up to 20 per cent of the coarse aggregate in fresh concrete mixtures, comparable performance and durability are attained with RCA. Still, when intended for fresh concrete, the recycled concrete aggregate has to be pre-soaked so as to not use the mix water and alter the end performance, as most RCA tends to have higher absorption values than natural aggregate.

External restrictions

External restrictions

The current limited use of recycled concrete aggregate in Canada is not only related to its properties or performance, but also due to ambiguous characterization of the product in national, provincial, or municipal material standards and building codes. Some specifiers completely omit it from their lists while others simply seem to lack full understanding of its capabilities, imposing unduly severe restrictions.

The Canadian Standards Association (CSA), for example, addresses RCA very loosely. A note to clause 4.2.3.1 in CSA A23.1-09, Concrete Materials and Methods of Concrete Construction/Methods of Test for Concrete, advises particular attention be paid to deleterious substances and physical properties, etc. Additionally, it states testing frequency may need to be increased to daily depending on the RCA source and variability. Notes are, of course, not mandatory to meeting the standard, and are really just ‘additional information.’ At the same time, however, CSA allows use of RCA as long as the resulting product meets its performance standards.

Other standards organizations prohibit the use of RCA altogether for use in fresh concrete. The Ontario Provincial Standard Specifications (OPSS) preclude the use of recycled concrete as an aggregate in concrete works. Additionally, OPSS 1001, Material Specification for Aggregates–Granular A, B, M, and Select Subgrade Material, does not allow the blending of aggregate products to improve physical properties.

While some authorities and project managers do not specify RCA at all, or only for certain projects or applications, others have such exacting specifications that they render the choice of recycled material all but impossible.

For example, the specifier for a current Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario (ETFO) project requires any RCA used in the cast-in-place concrete should be from a single-strength class—a robust 40 MPa that is not a very commonly used building material. Since adequate quantities of recycled material may have to be sourced from multiple locations with different original strength specifications, such a tight restriction effectively eliminates RCA as a viable option for gathering points toward the project’s LEED certification.

Photo courtesy Doug Hooton, University of Toronto

The City of Toronto also has standards in place that preclude the use of RCA for appropriate applications like unshrinkable backfill, commonly known as ‘u-fill.’ The city’s current specifications do not mention recycled aggregate as an alternative to virgin aggregate, thereby eliminating it by omission.

RCA in the field

RCA has been proven to offer similar or even improved properties for road base/sub-base due to characteristics like better compactability. In Europe, concrete containing between 10 and 20 per cent good-quality RCA is demonstrating a performance level equivalent to concrete made with virgin aggregate. While some differences have been noted in terms of higher porosity and material variability, the concrete has shown similar workability and strength development, with only certain limitations regarding durability.

In North America, RCA use is also on the rise. Departments of Transportation (DOTs) in Canada and the United States are choosing recycled concrete for various road applications with great success. A joint research program by Purdue University and the Indiana Department of Transportation (IDOT) to help decrease the state’s infrastructure costs by 10 to 20 per cent has led to the development of over 400 concrete mixes containing RCA. (This information comes from 2011 Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) of Ontario report, “State of the Aggregate Resource in Ontario Study, Consolidated Report,” published in 2011). In Michigan, recycled concrete has been a favoured material in more than two dozen MDOT projects since 1983.

Canadian specifiers and building organizations are also coming to appreciate the potential of RCA, which, up to this point, has been used mainly as granular material for road base. In fact, the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) of Ontario 2011 report, “State of the Aggregate Resource in Ontario Study, Consolidated Report,” identified more than a 100 per cent increase in annual use of recycled aggregate from 1991 to 2006, from 6 million to 13 million tonnes.

Greater Toronto Area (GTA) construction industry associations such as the Toronto and Area Road Builders Association (TARBA), Ontario Hot Mix Producers Association (OHMPA), Ontario Road Builders Association (ORBA), and Ontario Stone, Sand, and Gravel Association (OSSGA) are lobbying local municipalities to accept RCA as a green alternative to virgin aggregate for specific applications. Despite their efforts and the proven properties of RCA, many municipalities remain resistant. (Potential reasons for this hesitancy include a lack of information or experience with projects using the recycled material, reluctance to take responsibility for changing current specifications, or different views on long-term experiences.)

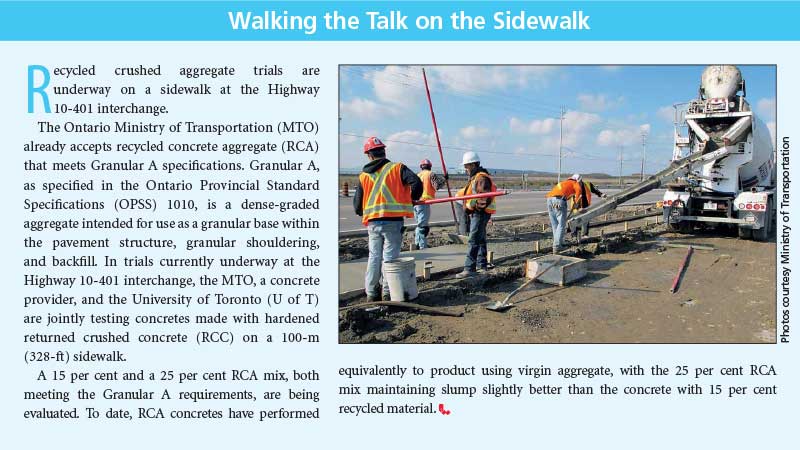

On the other hand, Toronto Pearson International Airport has identified RCA as a material of choice, specifying it as a base for the new aprons at Terminal 1 and using concrete recycled from the demolished Terminal 2 and its parking garage. The Ministry of Transportation of Ontario (MTO), which already uses RCA for road base and other applications, is conducting trials to expand its use of recycled materials in different concrete applications.

On the other hand, Toronto Pearson International Airport has identified RCA as a material of choice, specifying it as a base for the new aprons at Terminal 1 and using concrete recycled from the demolished Terminal 2 and its parking garage. The Ministry of Transportation of Ontario (MTO), which already uses RCA for road base and other applications, is conducting trials to expand its use of recycled materials in different concrete applications.

Aggregate manufacturers are also making RCA more readily available to serve the growing industrial and consumer demand for green products in Canada. A green concrete mix containing 60 per cent RCA is being offered by one manufacturer for the DIY market, while another company is even branding recycled concrete aggregate.

Conclusion

Recycled concrete aggregate is a readily available, flexible, and sustainable product that has a proven track record as a high-performance material for sub-base and other road construction projects. Up to a certain replacement level, it is also a viable substitute for virgin aggregate in concrete for an increasing number of applications.

Governments, standards authorities, industry associations, and builders in a wide range of sectors and in more and more parts of the world are taking notice of the performance properties and environmental benefits of RCA.

Uwe Schutz, PhD, is the director of product development and materials for Holcim (Canada). He is responsible for the co-ordination of all quality- and product-related aspects within the cement, aggregate, and concrete product lines. Before moving to Canada in 2004, Schutz worked for more than eight years as a senior consultant in various departments at the Holcim headquarters in Switzerland, supporting group companies in Asia, Europe, and the Americas. He can be contacted via e-mail at uwe.schutz@holcim.com.

R. Doug Hooton, PhD, P. Eng., is the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada/Cement Association of Canada (NSERC/CAC) Industrial Research Chair in Concrete Durability and Sustainability for the University of Toronto’s (U of T’s) Department of Civil Engineering. Over the last 38 years, his research has resulted in more than 200 publications on the durability of cementitious materials in concrete, as well as in the development of performance specifications for concrete. Hooton is a member of numerous Canadian Standards Association (CSA), American Concrete Institute (ACI), ASTM, and International Union of Laboratories and Experts in Construction Materials, Systems, and Structures (RILEM) technical committees. He can be reached at d.hooton@utoronto.ca.