Specifying fire-resistant materials is only part of the strategy

Wildfires are making headlines in Canada with increasing frequency. They are a frightening reminder about the impact of climate change. The Fort McMurray, Alta. wildfire in May 2016 prompted the most expensive natural disaster in Canadian history, though these reports of wildfires are no longer isolated incidents. The summer of 2021 saw significant destruction from wildfires in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario, with the number of fires and area burned both well above average. Canadian armed services and international fire fighting personnel were mobilized to support local crews. The long-term prognosis is grim as experts forecast more of the same in coming years. And yet, building in Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) zones continues at an accelerated pace.

WUI zones are the areas of transition between unoccupied land and human development; where structures and other human development meet or intermingle with undeveloped wildland or vegetative fuels. Communities adjacent to and surrounded by wildland are at varying degrees of risk from wildfires. WUI zones are not limited to densely forested areas; they can just as easily be inhabited areas close to brush or grassland. Dry, hot, and windy conditions—together with an ignition source—increase the risk of fire quickly spreading in any WUI zone.

In Canada, WUI zone regions are harder to identify than in the U.S., though it is estimated there are more than 32 million hectares (75 million acres) of WUI areas and 60 per cent of all cities, towns, settlements, and reservations across Canada have a significant amount of these areas.

Why are people still building, and rebuilding in WUI zones? Primarily for affordability. WUI zones continue to expand because of ongoing population growth and urban sprawl, driving significant housing development into environments in which fire is prone to move readily from forests and grasslands into neighbourhoods. There are also many who move to these picturesque locales for the privacy, natural beauty, and desire for active outdoor living.

Do not rely on codes to reach a higher standard of fire resilience

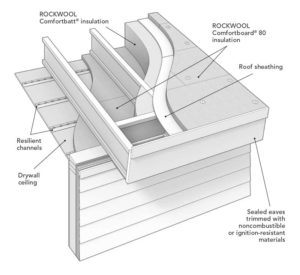

But homes in WUI areas must be built to a higher standard of fire resilience to increase odds of preserving structures and to provide occupants additional time to find safety. However, the means to achieve that resilience at times can be unclear. Often, the focus is placed on materials alone, with the thought that if noncombustible outer materials are selected, the rest of the home is protected. That said, fire protection is much more complicated than that.

What does code say? Building codes are often geared toward offering a minimal amount of fire protection. They outline the basic requirements a home must meet to be up to code, such as the types of materials that can be used, the assemblies that are preferred, and the minimum ASTM criteria that materials must meet.

National Research Council (NRC) Canada published a new guide for WUI zones in July 2021. Section 3.3 is useful, but vague on what is meant by ‘cladding.’ The author is a proponent of making continuous insulation a standard component within cladding systems; a fire-resistant assembly should include a water-resistive barrier as well as a noncombustible continuous insulation product, like stone wool rigid insulation boards, to protect vulnerable components.

The bottom line: codes are not enough; building or rebuilding a home with the greatest possible fire resilience is voluntary.