Solving the municipal infrastructure crisis

By Shantel Lipp

Beyond the traditional homes, multi-family buildings, and institutional/commercial/industrial (ICI) facilities, many design/construction professionals are regularly engaged with work on major infrastructure. Whether roads, sewers, transit systems, power utilities, dams, or telecommunications networks, these often high-profile and large-scale projects can be far more complex than a typical building.

They can also be more expensive to properly maintain. Given their impact on the built environment and society’s reliance on their functioning, this is a critical point. Earlier this year, for example, the collapse of a bridge overpass onto a busy Montréal motorway was but one incident that shone a huge spotlight on the bind Canadian cities find themselves in when it comes to maintaining and replacing basic municipal infrastructure.

Former London, Ont., councillor Gordon Hume—author of Taking Back Our Cities—says more of these incidents will happen in the years to come if no concrete action is taken to address the problem many municipalities face, thanks to substantial infrastructure deficit.

The cost of infrastructure upkeep

Current estimates from the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM)—an organization formed more than a century ago as the national voice of municipal government—peg the national municipal infrastructure deficit to be more than $123 billion. (For more information on FCM’s 2011 “Municipal Infrastructure Policy,” visit www.fcm.ca/Documents/corporate-resources/policy-statements/2011_Municipal_Infrastructure_and_Transportation_Policy%20Statement_EN.pdf).

“What we’re finding is municipalities have assets, in the case of a mid-sized city, in the range of $10 to 15 billion,” Hume explains, adding the problem is further compounded by the fact cities will never have the capacity to foot the bill under the current municipal funding model where they are at the mercy of provincial and federal governments. (For FCM’s online backgrounder, visit www.fcm.ca/home/issues/infrastructure.htm).

According to FCM, which represents 2000 communities across Canada, municipalities own 53 per cent of the country’s infrastructure, but collect just eight cents of every tax dollar paid in Canada. Under this equation, cities simply cannot keep up when it comes to infrastructure renewal. Within a standard business model, cities should be putting between one and five per cent of an asset’s value into a reserve fund. However, Hume says it is unlikely any municipality is even at one per cent on an annual basis of contributions toward total assets.

FCM’s “Municipal Infrastructure and Transportation Policy” proposes the federal government work with provincial, territorial, and municipal governments to:

- develop a comprehensive picture of the size, scope, and nature of the municipal infrastructure deficit; and

- commit to a long-term, national action plan to eliminate the deficit and address the underlying fiscal imbalance that is the cause of the deficit.

This plan could provide a solution in the face of decades of vast underfunding and under-spending, and an overall lack of political courage combined with a broken municipal funding model.

Hume argues part of the problem has been that roads and sewers have not been traditionally seen as assets; part of it is also political.

“When councils are faced with very difficult budget situations, one of the easiest things to cut quite frankly is water and sewer,” he says. “It’s underground, nobody sees it, and nobody cares. As long as you can turn the tap on in the morning and flush the toilet, who cares about their water and sewer? Now, the day you can’t do that,

it suddenly becomes important.”

Hume also calls the current municipal financing structure “old-fashioned and broken.”

“We need to have a national dialogue and understand that in the 21st century, you simply can’t build prosperous communities with a 17th century tax system and a 19th century governance model. You simply can’t do it,” he says.

Hume also points out there will need to be either a significant increase in the amount of funding the federal government provides to municipalities, such as an expanded gas tax or annual infrastructure program with some kind of building program, or municipalities and provinces need to start working out new tax opportunities.

The Saskatchewan difference

One such example Hume highlights is the new municipal revenue-sharing agreement between the province of Saskatchewan and its municipalities for operating costs—essentially, one per cent of the Provincial Sales Tax (PST) will go to municipalities.

Regina’s mayor, Pat Fiacco, says the agreement is a tribute to the relationship built between municipalities and the Saskatchewan government. It also means his city has been able to end the practice from leaner times where capital expenditures were often cancelled to subsidize operational expenditures.

“When decisions are made on programs for municipalities in all provincial departments, we ought not be told ‘this is the decision,’ we ought to be at the decision-making table ahead of time. We’re starting to see more of that. It’s a respectful relationship,” he explains.

However, Fiacco is blunt when it comes to the uphill battle cities face—he notes there is not the financial resources to deal with the infrastructure deficit; the original cost to Regina before depreciation for its assets is $1.8 billion, but replacing those assets would be $4.2 billion. (All figures in 2009 dollars). From 1991 to 2000, the mayor reports the city’s total capital expenditures was in the range of $553 million (adjusted for inflation). From 2001 to 2010, Regina increased those expenditures to $847 million.

“I’m proud of that because we’re putting our money where our mouth is, but we can only do more beyond that collectively,” Fiacco says. “Otherwise, how do we fund that gap? We can’t do it based on the current funding model. And that’s why we need a 20-year plan. It ought not just be for the lifespan of an elected political party or city council.”

After more than a decade as mayor, and time as the chair of FCM’s Big City Mayors Caucus, Fiacco says the infrastructure deficit and how to pay for it have been the most common topics of discussion among mayors across the country.

“The problem was everyone was essentially operating in silos, when we all have an obligation to really focus on planning, building, maintaining, and funding infrastructure together, no matter the size of the community,” he explains. “In fairness, if you look at the last number of years, we’ve gotten the Gas Tax and the Building Canada Fund. The federal government has provided more funding for municipalities than ever before. And I think they understand and recognize the need for a sustainable plan that will replace the Building Canada Fund when it expires in 2014.”

Fiacco also says what was missing in years past—collaborative effort between all government partners and the private sector—is increasingly looking like a real possibility, especially after the inaugural National Infrastructure Summit hosted in Regina in 2010, which brought together representatives from all three levels of government and industry with global experts.

“At the end of the summit, the resounding message was we can’t continue to do things the same way into the future,” Fiacco says. “We made the suggestion it would be in the country’s best interest to strike a national committee comprised of all orders of government and industry to look at potential, innovative, and sustainable solutions that would fit with a 20-year model, that outlines a plan with some clear goals and objectives, and a funding model that will respond to what we need.”

In addition to agreeing on the need for a long-term plan, both Hume and Fiacco maintain innovation and co-operation with industry will also be the keys to unlocking the looming municipal infrastructure crisis.

“There’s interesting innovation happening all around us that we could put into play here in Canada,” Fiacco says. “For example, at the summit, we heard from an expert from Holland that they use utility corridors under their sidewalks, rather than under paved streets. That helps when it comes to repairing those utilities—they have tiles versus poured concrete, so you can simply lift the tiles up and have access to underground infrastructure.”

Photo courtesy Look Matters

Planning for tomorrow’s pipes

The City of Regina is also investing in infrastructure by working with other Saskatchewan municipalities working with an organization called Communities of Tomorrow (CT)—a public-private partnership (P3) whose mission is to make Saskatchewan a global leader in the field of innovative sustainable municipal infrastructure. Working with industry, municipalities, and researchers, CT seeks to find innovative solutions to infrastructure challenges.

“Our version of sustainability is: can it cost less to build or can it cost less to run or can it last longer?” explains CT project manager Michael Zaplitny.

One of CT’s current projects could result in an innovative and efficient way to change out municipal water service connections, potentially saving municipalities across the province tens of millions of dollars. This initiative has been kicked off with a series of consultative meetings with municipalities across the province to find out which areas of infrastructure commanded the most attention and resources, and could probably benefit from an innovative approach.

“The number one issue that emerged across the board was water service connections, and that’s because every municipality has so many of them and eventually they all have to be replaced—no matter what they are made of,” says Zaplitny.

“The way this is normally done, is you would dig a big hole where the pipe is. That big hole costs money to dig and fill in and takes a substantial amount of time. The challenge was to see if we could find a way to do that work without digging and filling in big holes, so that they could be much more efficient at it,” he continues.

The CT team became aware the City of Regina was already using a system that significantly reduced the trenching necessary to replace a water line.

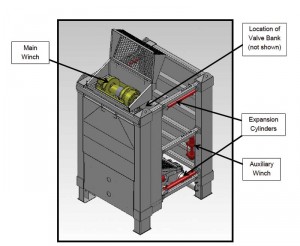

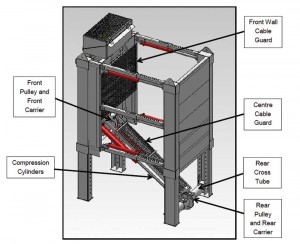

“They called it the ‘Super Winch’ and it was basically a winch in a box that they stuck in the bottom of a hole and used it to pull out the old pipe and put the new pipe in,” Zaplitny explains. “So, we wanted to find out if we could formalize, systematize, and turn it into a working tool that could be used in that context and others, and maybe in other municipalities as well.”

CT put together and facilitated a design team that was based in the public works and utilities teams of seven municipalities in Saskatchewan, along with:

- individuals from the National Research Council’s (NRC’s) Infrastructure Centre in Regina;

- scientists from the University of Regina;

- engineers;

- staff from the Saskatchewan Institute of Applied Sciences and Technology (SIAST); and

- some business people (in case it turned into a viable commercial project).

After four months of meetings, several recommendations on how the project could be accomplished, and the development of a rough business case, CT took the preliminary design to the Saskatchewan Research Council (SRC) to deliver the prototype.

Images courtesy Saskatchewan Research Council

“They engaged their design and technical staff to create engineering designs and source a supplier to build it,” Zaplitny explains. “They also took the prototype into the field for trials.”

The City of Regina was the first ‘living lab’ to put the prototype into the ground. North Battleford is also participating and Zaplitny hopes the trials will be completed before ‘freeze-up,’ so any modifications that need to be made based on the trials can be completed over winter.

CT also engaged some consultants to study the situation in Regina with these water lines and different approaches to replacing them.

“There are 50,000 total water service connections in Regina—of that, there’s about 7000 of them made out of this plastic pipe that was put in during the 1970s that are now failing,” Zaplitny says. “So with something like this, they can start to predict failure. If you know you’re going to have to replace it, you can then look at what methods you could use and how these methods affect the eventual cost.”

Zaplitny says that in terms of municipal asset management, the output is a model, which could potentially be used for almost any asset with a predictable failure rate.

“For example, if you have a certain amount of an asset and they fail on this curve, what are the different management techniques you can bring to that?” he says. “If you choose to just let your infrastructure fail, then you have an onslaught of costs and capacity issues because it all happens in a short period of time. Or, you can take a proactive approach and start years ahead and use methods that will give you progressive replacement instead of having a massive failure in a short, short period of time.”

Conceptually, Zaplitny argues this model will allow administrators to examine all options and make decisions that will hopefully save them money down the road.

“It also leads to some decisions about whether or not there’s a private-sector firm that might be interested in manufacturing it. The question becomes whether this will be a viable commercial entity and whether the prototype could be modified for use in other applications,” he says. “For example, during the field trials, an official with the City of Regina saw it and thought it could be used to pull a sewer replacement liner through a sewer, which is much larger than a water pipe—and it worked! So there’s a possibility that it could have a whole second life.”

Conclusion

If the project is viable and implemented in Regina, it could save the city $6 to $15 million over the projected life of the city’s water service connections. Hume thinks other municipalities can learn a great deal from this example.

“I’m really impressed with Communities of Tomorrow; they are doing some truly incredible work,” he says.

Armed with innovative ideas and a commitment from all partners to work together, Fiacco is hopeful a 20-year plan for municipal infrastructure renewal will indeed take shape.

“It won’t happen overnight,” he admits. “We’re in the process of putting the national committee together and we’re hopeful we’ll have some good news to report at the 2012 National Infrastructure Summit next September.”

Shantel Lipp is the president and COO of the Saskatchewan Heavy Construction Association (SHCA). She was hired in 2008 after a 10-year career working with elected municipal government officials of the Saskatchewan Urban Municipalities Association (SUMA) as its manager of member/corporate services. Prior, Lipp was employed by the City of Regina in both the property assessment/taxation department and assessment appeal board. She can be contacted at slipp@saskheavy.ca.