Showcasing engineered wood’s potential for modular design

In September, the Holcim Foundation for Sustainable Construction announced the winning projects for the North American region of its international awards program. One of the six recipients in the Next Generation category for young designers was Toronto’s Jonathan Enns (Enns Design/solidoperations). He was lauded for his concept of TimberLink—an interlocking panelized timber building system suitable for multi-family construction in remote areas. The idea combines Canada’s well-established tradition of using forest products with cutting-edge technologies.

Enns, a lecturer at the University of Toronto’s Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design, conducted the self-directed research project into the potential for using cross-laminated timber (CLT) to form a flexible assembly of clustered, inhabitable units in Cape Dorset, Nunavut.

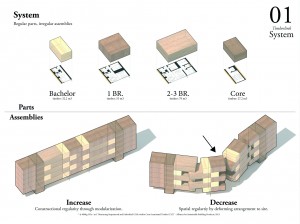

The modular nature means these multi-family assemblies could be site-specific, and deployed in different scales and configurations. Housing units could be stacked atop each other or, by means of a telescoping mechanism, entire assemblies could expand or contract.

“My initial ideas actually came from thinking about the irregularity and material inefficiencies of recent digital projects. This was an attempt to find a way to provide a similar level of site specificity while using units that still make sense in a mass production environment,” Enns told Construction Canada Online. “The hope is site-specific, unique, and singular constructions can be introduced to locations where standardized off-the-shelf constructions have typically proliferated.”

Enns’ idea was first sparked in 2009, after receiving a travelling fellowship from Princeton University to study CLT production facilities in Finland, Germany, and Austria. Cross-laminated timber involves large, multi-layered panels made from dimension lumber. When assembled in a platform-frame format, the effect can be comparable to suspended concrete slabs between load-bearing concrete walls to resist gravity and lateral loads. CLT panels can also be combined with post-and-beam wood frame or steel frame components. Vertically oriented panels can enclose a building, similar to tilt-up concrete, while the horizontally oriented panels span across beams to create floor plates.

“CLT is light in comparison to similar panelized systems such as prefab concrete,” Enns said. “Due to the cellular nature of TimberLink structures, CLT was seen as a desirable material because each partition can potentially bear load, and also for the simplification of delivery and foundation work caused by the lighter weight.”

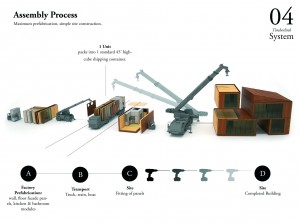

For Enns’ project, the panels would be prefabricated with insulation and cladding before assembly. This would both speed erection and reduce need for skilled labour onsite—important advantages for not only remote locations like Cape Dorset, but also for situations requiring quick deployment, such as disaster relief after a hurricane.

In one configuration, CLT housing units could be vertically stacked long above short, producing one regular side of alignment. Interlocking a second stack into the irregular side enabled expansion by pulling the two ‘columns’ apart while maintaining linear utility runs. Different configurations of stacking and expanding produce infinite possible outcomes in both plan and section, Enns explained.

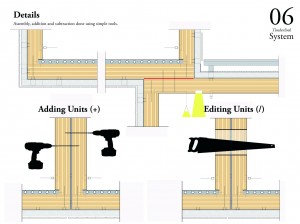

Currently, traditional remote construction can be expensive due to specialized imported labour and the need to transport materials. Enns’ TimberLink addresses these challenges through prefabrication. For one thing, the lighter-weight wood materials are more easily transportable than other traditional building products. For another, the ‘final’ CLT project would have a structural redundancy allowing onsite changes to take place using simple tools.

The CLT structure is also high in sequestered carbon. Using timber in place of alternate materials means thousands of tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) are prevented from entering the atmosphere. This can help offset the massive carbon costs of moving building products the distance to Cape Dorset.

The Holcim Foundation’s jury, comprising architects and academics from around the world, cited Enns’ “courage to revisit concepts pertaining to prefabrication in architecture, such as those explored by Konrad Wachsmann and Fritz Haller for the Habitat 67 model community in Montréal.” It said his project “aims to learn from history and further develop both construction and assembly to create more adaptable configurations—turning the logic of a quasi-neutral and anonymous system into one producing a site-specific architecture.”

Held every three years, the Holcim Awards honour “innovative, future-oriented, and tangible construction projects” that have not yet been built. In previous cases, winning a Holcim Award has helped spur the development of a theoretical project—almost half of all winners have now been built.

“The award was a phenomenal opportunity to compete at a global level with designers around the world,” Enns said. “It has given me verification the ideas are exciting to a global audience, but has also put the pressure on to realize the project, which I’m trying hard to make happen!”

“The hope is to find an industrial or development partner who is looking to [collaborate] to develop a first set of prototypes. There is a lot of input an industrial partner could bring to make this concept a reality,” he continued.”