Shifting gears: A Passive House car dealership in the making

Photo © Gansstock/Shutterstock

Ventilation

Car exhaust also contains harmful pollutants that must be directly exhausted outdoors. To meet code requirements, each of the six service bays required 11 m3 (400 cf)/m of exhaust pipe. Normally, all bays are connected to the same exhaust fan, leading to all of them being exhausted even when only one is in use. For this project, each bay was instead separately vented, cutting the exhaust rate by 83 per cent.

To further reduce losses, the team also explored supplying the make-up air directly to the car engines to avoid heating it. This setup was vetoed by the client, due to concerns over impact on servicing. Heat-recovery options on the exhaust, including heat-recovery ventilation (HRV), coaxial tubes, wrap-around coils, and heat pipes, were also explored. None of the manufacturers would warranty their equipment for use in car exhaust systems, rendering these measures infeasible. A further consideration was installing a ground earth tube to preheat the make-up air. The high air volume would require a large capacity at substantial cost. The average winter ground temperature in Red Deer is approximately 4 C (39 F), limiting the energy that can be extracted, and still necessitating the installation of a make-up air system. In the end, the additional heat loss of the exhaust had to be compensated through an improved building airtightness of 0.4 ach@50Pa. This was deemed achievable, given the experience of the architect and Passive House consultant (who had both previously worked on certified projects) and the larger size of the building.

Heating and cooling

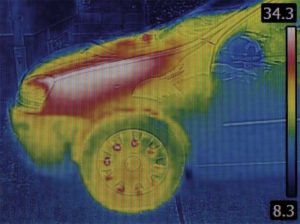

Image © Dario Sabljak/Shutterstock

Heating and cooling is provided by a ducted variable refrigerant flow (VRF) system, with indoor units concealed within the corridor’s suspended ceilings. The residential models were considered for cost savings, but concerns over equipment longevity steered the team away from this option. Electric resistance coils were installed in the supply air of each indoor unit to provide heat during peak heating conditions, when the heat pumps are expected to stop operating due to low temperatures. The capacity of the coils and heat pumps could have been substantially reduced if the heating loads according to PHPP had been considered in the design.

Despite the low nighttime summer temperatures and humidity levels in Red Deer, active cooling could not be avoided due to the solar and internal heat gains. The team tried diligently to reduce the size of indoor units, but the high solar gains in the showroom worked against this effort. Several scenarios were investigated in PHPP to estimate the peak cooling loads. A comparison of the results from the standard PHPP calculation (average load over the warmest 24 hours) of 11 kW and a worst-case scenario (e.g. peak three hours of solar gain, moveable shading not deployed, and maximum IHGs) revealed a five-factor difference in cooling load. The latter scenario’s result (52 kW) was relatively close to the engineer’s calculated load (57 kW). The results are consistent with findings from a PHI paper that revealed the PHPP cooling load algorithms are inaccurate when high solar gains are present (Figure 1). For more information, refer to Schnieders Jürgen: Planungstools für den Sommerfall im Nichtwohngebäude. In: Arbeitskreis kostengünstige Passivhäuser, Protokollband Nr. 41 Sommerverhalten von Nichtwohngebäuden im Passivhaus-Standard; Projekterfahrung und neue Erkenntnisse, Passivhaus Institut, 2012.