Reducing The Carbon Footprint: Updating and re-skinning building façades

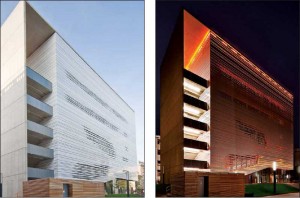

Photo courtesy du Toit Architects

355 Eleventh Street

The 2010 overall winner for the re-skinning awards was 355 Eleventh Street in San Francisco. Originally constructed in 1912 as a warehouse for a local brewery, the building had become derelict and an eyesore by 2008. Nevertheless, it was protected from demolition because of its historical significance. When a green building contractor bought the building to develop as its new headquarters, it aimed to make it a showcase of its commitment to sustainability and its proficiency in modern building techniques. Given the original warehouse’s generic utilitarian design and construction––corrugated sheet metal nailed to a timber frame––a successful refurbishment would be applicable to tens of thousands of similar old buildings in cities around the world.

The designers, Aidlin Darling Architects, faced a challenge in reconciling the new owner’s requirements of ample light and air with the city’s planning constraints that stipulated no new windows, and insisted any replacement of the outer corrugated sheeting had to be ‘in kind’ to maintain the building’s industrial character.

The solution was to fit the building with a new façade perforated with fields of small holes that allow light and air to pass through while screening out direct sunlight. Behind this new skin, they set opening windows to allow controlled cross-ventilation of the interior. The gap between the outer façade and the inner construction acts as an insulating buffer. A green roof was planted with drought-resistant native or adapted plant species for filtering stormwater, insulating the building, and decreasing the urban heat island (UHI) effect.

The building’s new skin not only prevents solar gain and provides passive cooling of the interior while meeting listed building planning constraints, but it also gives the building a facelift––transforming it from a mundane run-down structure to an esthetically attractive modern building. Due to its natural ventilation and lighting and thermal buffer, among other improvements, the building is extremely energy-efficient and has received LEED Gold certification. The re-skinning methods used on 355 Eleventh are low-tech, cost-effective, and could be replicated on a global scale.

The Palms

The 2011 overall winner was The Palms in Venice, California––a private house whose owners wanted to add livable space for their relatives without increasing their home’s footprint. They also wanted to implement sustainable technologies to minimize its carbon footprint.

Photos © Hendrik Daniel

The design team––architects Daly Genik, structural engineers Energy Code Works, consultants Title 24, and landscape architects Polly Furr Venice Studio––came up with a solution where the addition of an exoskeleton armature of corrugated recycled steel panels supports new balconies, giving the small property 214 m2 (2300 sf) of total living space. All indoor space opens to outdoor space, maximizing airflow and minimizing the need for cooling in summer. The exoskeleton also dampens sound and provides shading for the house’s inhabitants. The steel exoskeleton is an easily reproducibly design, a variation of which Daly Genik has already used to upgrade the façade of a charter high school in Los Angeles.

Green performance

First Canadian Place, 355 Eleventh Street, and The Palms are examples of excellence in re-skinning and are helping to drive innovation in green building, along with energy efficiency construction programs such as LEED, Energy Star, and Germany’s Passivhaus standard. However, as mentioned earlier, building energy efficiency is not just about the infrastructure, but about occupant behaviour as well.

LEED, Energy Star, and Passivhaus have set benchmarks for what can be achieved in building construction or refurbishment, but the standards alone are not enough. As currently specified, they do not account for occupant behaviour once the projects are completed. This can undermine the whole purpose of such standards if energy-efficient light bulbs are fitted and left on all night, if windows are fitted for passive cooling but are shut and an energy-intensive air-conditioner is turned on instead, or if taps are left running. Unfortunately, there are numerous examples where LEED-certified or other low-energy specification buildings have been found to perform no better than comparable buildings with no rating.

The problem is rating systems such as LEED only predict how a building might perform, and do not measure how it actually performs. If carbon emissions can be cut by any significant amount, the way people behave inside these buildings also has to be changed. Conforming to a rating system like LEED will ensure the occupants have all the tools they need to operate the building efficiently and sustainably, but there has to be a way of making them aware of how they are using energy. To do this, energy use must be made more tangible.

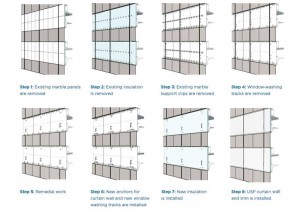

Images courtesy B+H Architects

The problem with carbon emissions is they cannot be seen. It is not just that CO2 is a colourless gas; most emissions are elsewhere and out of sight––certainly when it comes to electricity. Unless one lives in view of a power station and can see the smoke rising out of the stacks, one will not see the emissions produced by the electricity generated when enjoying the breeze of the air-conditioning system while working at the computer or relaxing watching TV.

To make energy consumption visible, people must first measure it. This is already being done in a crude way via meter readings for energy bills. However, this provides a number without any context. A person cannot tell by looking at the bill whether he or she is an efficient energy user. One way to find out would be to compare energy efficiency with his or her neighbours. One would also need to create a metric to allow him or her to make a comparison adjusted for the relative size of the buildings. The easiest way to do this is to divide the total amount of energy consumed by the area of the building to give a rating of energy per square metre. Now, like can be compared with like, and the performance measured against others.

If people collected these measurements on a wide scale––energy consumption divided by area––the performance of all the buildings in a neighbourhood, district, or across an entire city could be compared. People would see which buildings performed best and which performed worst, compared on a like-for-like basis. This would enable people to create a new definition of a green building: one that performs in a green manner.

Instead of just a building’s age or energy efficiency designations to make assumptions about its performance, actual performance is measured, which is determined by the infrastructure in addition to occupant behaviour. Only by aligning infrastructure and behaviour can people maximize the energy efficiency potential of buildings and reduce their emissions.

By measuring and comparing building performance as described above, benchmarks can be developed. These can be invaluable in bringing about change. There are already numerous organizations to capture and compare their energy use data, and reveal opportunities to change. For example, a company is working with Ontario school boards where it is able to show how the energy use of individual schools––standardized as a per student or per square foot measure––compare with each other. Using this benchmark, school boards can quickly see which schools in their localities are using higher amounts of power and thus incurring higher costs.

Some of these differences might be traced back to building age and inherent energy efficiency or inefficiency of their infrastructure, but the other key component is behaviour. By providing objective benchmarks, the company enables key stakeholders––including students, teachers, parents, and administrators––to identify where savings can be made and work to reduce energy consumption.

Much could be accomplished if entire cities could be re-skinned and building occupant behaviour could be changed, the same way schools in Ontario are. Saving energy is far more cost-efficient than making energy. With the Ontario schools example, the company estimates the cost of building a megawatt (MW) of generating capacity in the province is $300,000. By contrast, the cost of saving one MW of electrical capacity is $10,000 per year. This is a ratio of 150:1 for the return on investment (ROI). Re-skinning buildings and giving occupants the tools to maximize their energy efficiency is time and money well spent.

Ron Dembo, PhD, is the founder and CEO of Zerofootprint, a cleantech software and services company that makes environmental impact measurable, visible, and manageable for corporations, governments, institutions, and individuals. He is the founder and former CEO and president of Algorithmics, and a former professor of operations research at Yale University. Dembo can be reached via e-mail at ron.dembo@zerofootprint.net.