RCMP E division headquarters project takes the gold

By Teresa (Reece) Sims

With 25 operational units formerly dispersed throughout the Lower Mainland of British Columbia, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) E Division Headquarters in Surrey comprises the country’s largest division. Approximately one-third of the entire force is located in the province, and the existing facilities were neither purpose-built nor suitable in terms of space, adjacencies, systems, and technology. Therefore, it was determined a new facility—built adjacent to the city’s Green Timbers Urban Forest—was critical to maintain operational efficiency.

The Government of Canada developed a public-private partnership (P3) agreement between the Green Timbers Accommodation Partners (GTAP) and Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC). As part of the agreement, GTAP designed, built, financed, and will maintain the facility for the next 25 years. The relocation project brought all 25 offices into a single, purpose-built headquarters in Surrey.

As the largest federal accommodations project outside the National Capital Region, the RCMP E Division Headquarters was completed in December 2012. The facility is a unique, multi-disciplinary, fast-tracked, complex project that improved the RCMP’s federal, provincial, and municipal operations. The new facility also provides sustainable, purpose-based office accommodations to more than 2700 personnel.

The 76,162-m2 (819,800-sf) facility comprises three buildings strategically designed to enable greater collaboration between international, national, provincial, and municipal partners. The campus is complete with a seven-storey administration and operations centre, a post-disaster emergency operations centre, and a warehouse facility including workshops, garage and vehicle bays, and parking for more than 1800 fleet, staff, and visitor vehicles.

Through a selection process a consortium was chosen to carry out the project. The team included:

- consortium sponsors InfraRed Capital Partners (formerly HSBC Infrastructure) and Bouygues Bâtiment International and Bouygues Energies & Services Canada (formerly ETDE Facility Management Canada);

- architectural and interior design firm Kasian Architecture Interior Design and Planning Ltd.;

- Bouygues Building Canada and BIRD Construction Joint Venture; and

- Bouygues Energies & Services Canada (formerly ETDE Facility Management Canada).

Lifecycle planning and sustainability

Early in the design phase, it was evident sustainability was a key focus for the project team. The consortium’s approach to sustainability was to seek total dedication and collaboration among all designers to maximize the environmental, social, and economic benefits at the RCMP E Division Headquarters.

When preparing the project, designers considered the effects of the proposed development on the local and wider environment, and considered sustainability in both the design and specification of materials. This ensured the RCMP facility would remain efficient throughout its lifetime. The environmental aspects requiring future management or maintenance were highlighted early in the design stage.

To earn Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) New Construction (NC) Gold Certification, the credit targets were incorporated from early in the design phase and continually carried forward through the construction phases. During the project phases, the team worked with the LEED consultant’s updated sustainability credit list, as well as tasks and deliverables checklists. These lists were coupled with monthly LEED meetings to review the status of achieving the targeted project credits. The monthly review facilitated achievement status and improved the likelihood of success.

In meeting with the project team, it was established energy management, material selection, resource efficiency, biodiversity, water efficiency, and connectivity to the natural environment were critical for meeting LEED Gold requirements.

Energy management

Since energy management was one of the priorities for the design team, considerations were made to use energy-efficient equipment, ensure the building’s orientation harnessed optimal natural light, and control airtightness. The creation of a passive design to ensure effective use of the campus microclimate and optimize building orientation was essential. While planning the layout of the three buildings, the design of north and south building façades were substantially larger than the east and west faces, thereby maximizing control of sunlight glare and heat gain/loss. Initiatives such as this reduced the mechanical system’s size within the facility and significantly decreased energy consumption.

In conjunction with GTAP, Stantec Consulting, Integral Group (formerly Cobalt Engineering) and Kasian registered for B.C. Hydro’s New Construction Program brief in the design process to complete an extensive whole lifecycle energy-modelling analysis.

The study concluded there were 10 main energy-conservation measures that could be combined to save more than 3.7 gigawatt hours of electricity annually. This equated to an 18 per cent energy reduction relative to American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) 90.1-1999, Energy Standard for Buildings except Low-rise Residential Buildings.

The energy-conservation measures used during the construction of the buildings included:

- increasing roof insulation to R-30 and wall insulation to R-20;

- improving the glazing insulation to R-3.12;

- installing a water-side economizer to cool the data centre;

- incorporating a variable refrigerant flow (VRF) system in the post-disaster building;

- installing variable-speed drives on all pumps and fans;

- employing interior and exterior lighting controls;

- reducing lighting density by 20 per cent on the interior and 15 per cent on the exterior;

- using the heat from the data centre and telecommunications rooms to provide hot water and heat to other areas of the facility; and

- installing a chilled-beam HVAC system in the main building.

Chilled-beam HVAC systems

Of the various energy-conservation measures implemented, installing a chilled-beam HVAC system in the main building was the most innovative development. Despite chilled-beam systems having been used in Europe and Australia for years, they are a relatively new concept in Canada. Specifically in Western Canada, only a handful of such systems have been installed in buildings, making the RCMP project’s installation the most extensive in the region.

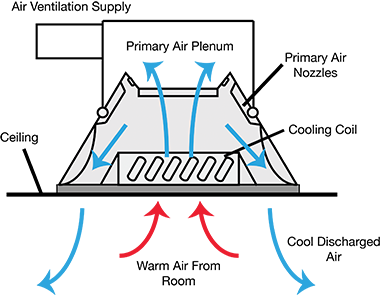

Chilled-beam systems are an alternative to variable-air volume (VAV) systems for cooling and ventilating spaces where an indoor environment and individual space control is valued. There are three main types: the passive-chilled beam (PCB), active-chilled beam (ACB), and integrated/multi-service beam (MSB).

Located within a space, all chilled-beam systems use water to remove heat energy from a room. The predominant difference between PCBs and ACBs is the way in which airflow and fresh air are brought into the space. PCBs require ventilation air to be delivered via a separate air-handling system whereas with ACBs, the ventilation air is delivered to the beam by a central air-handling system via ductwork. This induction process allows an active-chilled beam to provide more cooling capacity than a passive chilled beam. Additionally, MSBs—a relatively new development—can be installed as either an active or passive chilled beam system, but integrate additional building services such as lighting, speakers, sprinkler openings, and cable pathways into their build-out.

The ACB in the main RCMP E Division Headquarters building consists of a fin-and-tube heat exchanger contained in a housing suspended from, or recessed in, the ceiling (Figure 1). Warm air rises and is chilled by cooling coils in the chilled beam. Once the air cools, it falls down to the floor where the cycle starts over again.

Figure 1

Due to National Energy Code of Canada for Buildings (NECB) 2011 requirements in the British Columbia building code, outdoor air had to be supplied to the indoor spaces via a dedicated outdoor air system (DOAS). The active-chilled beam does not contain a condensation draining system. Therefore, the DOAS must keep the dewpoint of the indoor air below the surface temperature of the chilled beam to avoid moisture from condensing on the coil and leaking into the space.

Despite the need to prevent condensation, the risk of a greater number of leaks, typically higher installation costs (in comparison to a VAV system), and complex installation challenges, the project team believed the long-term benefits of employing a chilled-beam system in the design outweighed the potential drawbacks.

The consortium team worked together extensively to ensure potential drawbacks were minimized. Since this was a P3 project, design and construction were occurring simultaneously and resulted in short timelines for schedule and budget requirements. Nevertheless, the project was completed within the overall construction budget.

Additionally, the project team used building information modelling (BIM) to carry out extensive clash detection pre-construction. This eliminated potential constructability issues for the active-chilled beam installation, mitigating costly delays and additional construction expenses.

The active chilled-beam system’s benefits include:

- reduction in energy use in comparison to a traditional VAV system;

- improved space ventilation;

- smaller ductwork and air-handling units required due to a 50 to 65 per cent reduction in air required in comparison to a VAV system;

- minimal maintenance required as there are no moving parts and no filters to maintain;

- near-silent system noise; and

- more uniform space temperatures achieved in rooms.

Material selection and resource efficiency

Material selections were based on local availability, and construction methods were designed to reduce waste. Locally sourced materials were used wherever possible. More than 35 per cent of materials were regionally based as per LEED Materials and Resources (MR) Credit 5, Regional Materials. Additionally, 80 per cent of construction demolition and land-clearing waste was diverted from landfills. Further, use of Forest Stewardship Council (FSC)-certified wood—as noted in the province’s Wood First Act—was used for more than 50 per cent of all wood-based materials incorporated into the project.

Biodiversity, water efficiency, and connectivity to the natural environment

One of the main intentions behind the project’s design was to embody the history, tradition, and culture of the RCMP, while connecting to the natural site. As noted, the building envelope was designed to be highly efficient and minimize the 76,180-m2 (820,000-sf) facility footprint. This was accomplished by creating three separate buildings comprising a multi-level campus and employing long spans to maximize space and flexibility. Expansive windows and angled brick masonry also references tree trunks in the structure’s natural surroundings. Red and blue, the colours of the traditional RCMP serge uniform, as well as green, were used to create colour zone divisions for each section of the facility. Each colour was employed as an accent at vertical circulation components to support intuitive way finding.

Careful design considerations were given to retaining existing heritage trees and ensuring the main entryway complemented the natural esthetic. While the site plan was designed to accommodate and minimize impact on the Green Timbers Urban Forest, it permits a 30 per cent expansion to accommodate any future growth of RCMP operations.

The facility’s design resulted in a more than 47 per cent water use reduction over baseline fixture performance requirements. Similarly, there is no potable water used for irrigation of the landscaping in the campus. Some of the innovative design elements contributing to the water reduction include low-flow plumbing and rainwater capture. Further, a retention pond that irrigates the surrounding flora is circulated to the building to provide water for the vegetated roofs installed on two of the campus buildings. These roofs create a closed loop system with the retention pond as they are planted with natural vegetation, filter pollutants and carbon dioxide (CO2), reduce energy costs, and help manage storm water.

Lifecycle management

Lifecycle management was an important factor in the planning and design of the RCMP E Division building. With a building as large as this headquarters, the process pathways of the facility maintenance crews were considered in the design process. Initial design concepts incorporated policy framework requirements, as communicated in a facility management design manual.

Since ETDE Facility Management Canada will be maintaining the building for the next 25 years, it was important the building was designed to be functional and durable for that time. Further, if replacement was deemed necessary, replacement value and ease of access needed to be carefully considered. Every aspect of the project design including material specification and location were previewed by the facility maintenance group. Shop drawings were reviewed and signed off or questioned by the facility maintenance provider as part of the regular shop drawing review process. The loading bay facility layout and its adjacency to clear and direct circulation paths for delivery of goods were carefully planned with the facility maintenance providers.

Additionally, to ensure the green building features installed were being operated correctly to achieve the desired energy savings, the consortium was directly tied into a contract that guaranteed the amount of energy used was measured and verified regularly. This ensured all the facility’s energy-consuming elements—including lights, computers, and mechanical equipment—were sub-metred and monitored for optimal energy efficiency.

Conclusion

Due to the sustainability features such as the chilled beams, efficient lighting systems, and other environmentally responsible technologies, it is anticipated the RCMP E Division Headquarters will use 18 per cent less energy than a comparable building of its size and save nearly $160,000 annually in utility costs.

These energy savings, coupled with a long-term design vision, integrated facilities management plan, and sub-metering regularly measured and verified by the consortium program, have created a new benchmarking standard for major government institutional buildings.

Under the strategic direction of the design team, the facility successfully enhances the RCMP’s ability to provide integrated, intelligence-based policing, improves overall communications and response times, and acts as a design marvel and model of sustainability for both civic and P3 facilities alike.

Note:This article was written with contributions from W. Scott Douglas, AAA, AIBC, MAA, and Ajaz Hasan, AIBC, MASA, LEED AP BD+C.

Teresa (Reece) Sims, is the owner of Reece Sims Branding + Strategy and ACE PR which specializes in working with architecture, construction, and engineering firms. She can be reached at hello@reecesims.com.

Teresa (Reece) Sims, is the owner of Reece Sims Branding + Strategy and ACE PR which specializes in working with architecture, construction, and engineering firms. She can be reached at hello@reecesims.com.