Passive House goes to work

The structural and cladding sub-trades did not have to do anything different, and the crew with training in high-performance envelopes came between them to do the sensitive work.

The exterior building envelope comprises I-joist Larsen trusses with cellulose insulation and an unsupported, vapour-open weather-resistant barrier (WRB) membrane. This wall system was chosen for its thermal performance and cost effectiveness, and has been used on several other smaller local projects with success. This is the first time this design team (the author is a part of it) used this envelope at a larger scale.

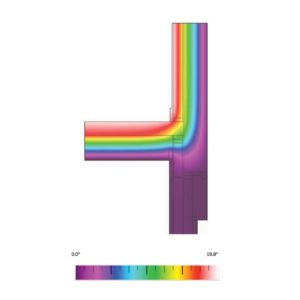

Significant efforts were made during design to reduce envelope penetrations in the build. The final design contains minor wood thermal bridges at key structural locations in the floor as well as façade attachment places. The Passive House Planning Package (PHPP) also confirmed these are insignificant relative to the scale of the building, and do not pose any challenges.

Energy modelling

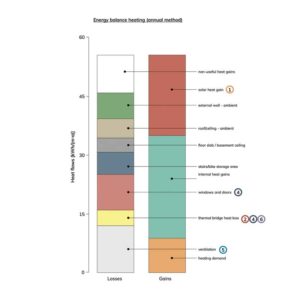

PHPP is required to track overall certification criteria and quantify the effects of thermal bridges. However, on a project of this scale, it lacked the granularity needed to accurately evaluate heating and cooling loads and overheating risk on a zone-by-zone basis.

Hence, a third-party hourly analysis program was used to create a dynamic simulation of energy movement and demands within the building (i.e. capable of computing the period of peak heating and cooling demand for separate rooms and zones within the building, and isolating the specific interactions between solar gains, occupancy, internal gains, envelope losses, and air exchanges). A tool of this sophistication is normally used on commercial projects, regardless of Passive House certification, and provides the information needed to make optimized selections of HVAC terminal units (e.g. fan coils) to suit peak zone loads versus plant equipment (e.g. boiler, chiller, variable refrigerant volume [VRV] heat pump) to address dynamic peaks of the building as a whole. It also allows the grouping of zones served by separate sub-systems with unique operating schedules and equipment efficiencies.

HVAC design

The West Coast has mild winters and summers. Most buildings in this region do not have active cooling. However, the internal gains of an office meant active cooling was part of the design from the start. Summer overheating has been identified as a problem in several residential Passive House buildings, and in this project, the risk was amplified by the internal gains of an office.

Demands for cooling were reduced by selecting efficient lighting systems and strategically placed glazing with solar control. However, even with these measures in place, the preliminary energy model for the project predicted 34 kWh/m2-yr of internal gains. A portion of these gains are useful in the winter months, and in the summer, some of it will be exhausted from the building through the heat recovery ventilation (HRV) system. However, these measures were not enough to negate the need for active cooling.

The thermal demand that must be actively provided for both heating and cooling is met by a VRV system. It was selected for its ability to provide simultaneous heating and cooling in different zones and to internally recover heat as well as its high efficiency cooling operation.