On the history highway

by nithya_caleb | December 14, 2018 1:52 pm

[1]

[1]by Nithya Caleb

Construction Canada has entered its 60th year. A quick look through issues past and present confirms the magazine has remained true to its mission of providing architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) professionals with information on building materials and methods, their applications, and construction industry trends.

Initially called Specification Associate, it was published first as a quarterly in 1959 by Russell Cornell, the magazine’s first editor, along with Bob Fernandez and L. Stuart Frost. At the time, the Specification Writers Association of Canada (SWAC) was approaching its fifth birthday—there were only three chapters (Toronto, Montreal, and Ottawa), and the national “office” was really the Frost-Fernandez workplace.

In 1962, the magazine switched to a bimonthly schedule. Five years later, Cornell retired, and editor Stuart Frost brought a new look to the magazine, adding chapter news, letters to the editor, and more features for manufacturers and building contractors.

In the late 1970s, the magazine went through a transition, in a way mirroring the change happening at the association level—SWAC had by then transformed into Construction Specifications Canada (CSC). Specification Associate’s editorial calendar was refined, the design overhauled and finally, in July 1980, it became the now-familiar Construction Canada.

In 1998, Kenilworth Media Inc., the magazine’s current publisher, began producing the magazine. Two years later, the F. Ross Browne Award was introduced to acknowledge article authors—the honour taking its name from the last president of SWAC and first president of CSC who is known for his passion for effective communication, and for speaking his mind. He brought this attitude to a column called Curmudgeon’s Corner, which appeared in Construction Canada from July 1998 to November 1999.

Today, the print edition has grown to nine issues with more than 12,000 readers.

The last decade has seen a big push into the digital realm. The magazine now has a significant online presence as well as a digital edition. The website[2] aims to keep readers up-to-date with industry news as well as present a searchable knowledge base of past articles. The platform has also provided Construction Canada with the opportunity to cover topics not suited to a magazine format. More recently, social media has opened up new avenues (@constructcanmag[3]) to interact with the AEC community.

The construction industry is at another crossroad. As new technologies begin to change the paradigm, Construction Canada will continue to bring relevant information about materials, methods, codes, and standards, for specifiers, architects, engineers, and other building professionals.

The way it was…in 1858

In its November-December 1974 issue, Specifications Associate took a trip to the distant past with the assistance of spec writer Milton Seddon. He obtained drawings and specifications prepared in 1858 by the Public Works Department. The contract was for 13 courthouses and jails to be constructed at several locations in Lower Canada. Terminology in the specification includes “shewn on drawings” and “shewn as detailed.” Several other terms and phraseology that many specifiers today have possibly never heard or used are:

- Flues to be well cored and pargetted with cow manure

- Masonry to be “rough picked or scabbled on face”

- Cut stone “steps in long lengths and broad flags, rough bouchard on face”

- Moulded emblatures

- Spandrils and sofite casings

- Cradling and bracketing

- Angle beads of inch stuff

- Glass of best English or german sheet glass free from specks or veins, etc.

- Roof of best eastern township or kingsey slates

- An upright hot air furnace with tin tubing

- Flatted cedars laid 18 inches apart in the clear

- Smith-made bolts and thumb latches

- Tinning lapped in the most approved Lower Canada manner

Seddon goes on to write:

From glancing at the specification, the most interesting thing to note is the absence from the great number of individual trade sections that we know to-day. The specification is written “to the Contractor” and believe it or not, that is what still should be maintained to-day when writing a stipulated sum contract. As a grand finale, we wonder if what appears to be the name of the specification writer (or architect) isn’t really an opinion expressed by the Contractor. The document is signed “Rubidge”.

The specified slider does not exist.

[4]

[4]How the CN Tower was constructed

For six decades, Construction Canada has been featuring challenging projects and engineering marvels to inspire readers to expand their horizons and find innovative applications for available building materials. The March/April 1973 issue of the Specification Associate carried a lengthy article on a Canadian marvel, the CN Tower, when it was under construction. An excerpt:

The tallest self-supporting structure in the world — an 1807-foot communications and observation tower to be known as CN Tower — is scheduled for completion in Toronto in 1974.

The multi-million dollar Tower will be one of the engineering and architectural wonders of the world.

Construction techniques are unusual. The site will be excavated through 35 ft. of overburden into some 20 ft. of rock and the foundation laid. Special forms will be set up and a concrete shaft will be poured continuously, round-the-clock, using a slipform method. The Tower will rise at the rate of 16 ft. a day.

To maintain non-stop operation, set of forms will be elevated by a ring of “climbing jacks” around the structure. As the forms move up they will leave a continuous extrusion of hardened concrete, reinforced by steel rods.

When [the] concrete reaches the 1500-ft. level large prefabricated supports of steel and concrete will be secured to the main shaft at [the] 1100-ft. level. Twelve supporting steel units will hold the deck on which the Sky Pod will be constructed. Then the 220-ton main antenna will be assembled at the base in sections, raised to the top and fixed in position.

The CN Tower held the record as the world’s tallest freestanding structure for more than 30 years, until the construction of Burj Khalifa in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, in 2007. Designed and built by Webb Zerafa Menkes Housden (WZMH) Architects, John Andrews Architects International, and a team of engineers and contractors, the tower was completed in 1976.

CN Tower’s significant contributions to Canada’s architectural history and continuing relevance earned it the 2017 Prix du XXe siècle from the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) and National Trust for Canada.

Word processing lessons

[5]

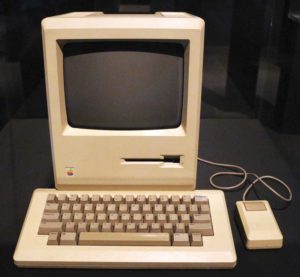

[5]Laptops, iPads, and smart phones are ubiquitous in this day and age. However, in the 1980s, desktop computers were making an appearance and word processing programs were a novelty and yet another skill for specification writers to master. In the November/December 1987 issue of Construction Canada, Wayne Watson, FCSC, RSW, CCS, addressed computer word processing for the preparation of project specifications.

What types of word processing programs are available? There are only a few good programs available for the Apple MacIntosh. The IBM PC and compatibles enjoy an offering of over 100 word processing programs offering various degrees of flexibility and ease of use.

Word processing software edits text in computer memory, and is either of two configurations. The first it terms “page oriented” and the second is “document oriented”. The “page oriented” word processing packages date back to the 1970s when the cost of computer memory, storage media, and floppy drives [was] expensive. This program type was structured to handle one page of text at a time. Processing of text is slow and awkward. Moving a paragraph of text from one page to another is cumbersome. Repaginating the document (or specification section) is slow.

The “document oriented” programs can load an entire document, or at least a major portion of that document into memory for rapid manipulation of text during the editing process. Why should you be concerned over which type is better? The basic difference is speed of operation. The latter is preferred for specification editing.

The specification writer of tomorrow: A forecast from the past

[6]What did engineers in the 1960s think the role of specification writers would be in today’s construction industry? An article by J. P. Huza, P.Eng., in the June 1963 issue provides a clue. Here is an excerpt.

[6]What did engineers in the 1960s think the role of specification writers would be in today’s construction industry? An article by J. P. Huza, P.Eng., in the June 1963 issue provides a clue. Here is an excerpt.

During his scholastic period, he [the specification writer of tomorrow] will have taken courses in systems and materials applications, and also specialized courses in engineering reports and engineering law… He will be an individual of a well-rounded technical background who could, and will, contribute to all phases of the planning functions, and will specialize in the composition and make-up of specifications. In the office, the specification writer of tomorrow…will contribute greatly to the selection of systems and materials, from the standpoint of both economics and correct applications. In other words, he will be an integral part of the engineering design unit… And, of course, the specification writer of tomorrow will have available standard specification formats produced by the Specification Writers Association of Canada which will be of immeasurable assistance to him.

The white building – then and now

[7]

[7]Toronto’s 72-storey First Bank Tower has been featured twice in Construction Canada. In the March-April 1974 issue, Roland Bergmann, P.Eng., wrote a paper on the First Bank Tower, a part of the First Canadian Place development then under construction. Bergmann was the principal-in-charge of the tower design. The paper dealt with the development of the concept of the structural system, a technical description of the structural system, and the analysis of the tower structure.

The structure of the tower is an all steel frame, consisting of the perimeter framed tube, which resists all lateral forces, and an interior framing designed for gravity forces only. The basic floor to floor height is 12’-8 with a 9’-0 ceiling. The exterior of the tower is clad in white marble, which extends into the lobbies at the ground floor and concourse levels below grade.

In the article “Seeing Through Rose-coloured Glasses[8]” (March 2017), Julie Schimmelpenningh briefly describes the facelift the First Canadian Place received in the early 2000s.

On a stormy spring evening in 2007, a marble panel fell from the 60th storey of Canada’s tallest building. Although no one was hurt, the event called into question the safety and durability of the building’s aging façade, made of 45,000 marble panels, each weighing around 100 kg (220 lb). It also sparked a multi-phase renovation project years later to remove and replace the marble panels with a material that would not only ensure safety and energy efficiency, but also give First Canadian Place a memorable facelift.

Today, many refer to First Canadian Place simply as the ‘White Building.’ In 2009, the building owner swapped out the marble exterior with 34,840 m2 (375,000 sf) of laminated glass featuring a white interlayer. Nearly opaque, the ceramic-fritted spandrel panels were chosen for their functionality and esthetic—they conceal both plumbing and HVAC systems running between the floors and have revamped the building with a modern, clean, and easily identifiable design.

The specified slider does not exist.

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/CC-60-years-logo-final.jpg

- website: https://www.constructioncanada.net

- @constructcanmag: https://twitter.com/ConstructCanMag

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/bigstock-Toronto-Cn-canadian-National-129980774.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Computer_macintosh_128k_1984_all_about_Apple_onlus.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/sb1-JP-Huza-P.Eng-.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/s6-image-1.jpg

- Seeing Through Rose-coloured Glasses: https://www.constructioncanada.net/seeing-through-rose-coloured-glass/

Source URL: https://www.constructioncanada.net/on-the-history-highway/