Montréal architects weave ‘shoebox’ home across the site’s landscape

Photo courtesy TBA/Adrien Williams

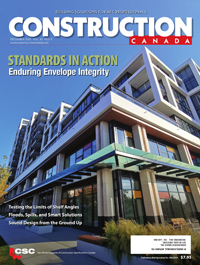

Located in the fast-developing Rosemont-La Petite-Patrie borough of Montréal, Qué., deNormanville is part of the first wave of post-moratorium additions exploring new avenues for the transformation of the city’s disappearing one-story typology, commonly referred to as ‘shoeboxes.’

By taking the preservation of the original structure and the site’s mature trees as its primary point of departure, the project designed by Montréal-based Thomas Balaban Architect (TBA) responds in a straightforward but radical way to the principal challenges of designing an addition to the small, vernacular structure set at the rear of the lot. Weaving across the site’s landscape, it reaches out to restore the continuity of neighbouring façades. While the old structure finds itself preserved at the heart of the new home, the project reestablishes the presence of the one-storey typology in the heterogenous family neighbourhood dominated by Montréal’s renowned ‘missing middle’ plex housing.

Having owned the property for several years, the clients wanted to expand their tiny back lot home to accommodate their growing family. This meant additional bedrooms, larger living spaces, and spatial separation between the private rooms and socially focused areas. From the onset both client and architect shared the desire to conserve the single story and its direct connection to the surrounding outdoor space. Realizing their desired home with limited means was a three-year long process, they explored a variety of options that could reconcile needs, budget, and zoning. In the end, the front yard extension that layered indoor and outdoor space remained the most feasible and exciting prospect.

The layered volume developed step-by-step. The first move brought the extension forward to align with the frontage of its immediate neighbours; its façade carved out to provide a protective space around a Siberian elm that interrupts the continuity of the façade’s alignment. This satellite volume is then connected back to the original house via a corridor running along the east firewall of the property. The exterior wall of the corridor is blended into the street front volume with a curve reflecting the tree well on the front façade, delineating the central outdoor courtyard that showcases the original house. The result is a sinuous boundary between interior, architecture, landscape, and urban context.

The house’s new front yard, mid yard, and backyard structure clearly defines the home’s internal configuration. Quiet spaces such as the bedroom and living room are reorganized within the original masonry and wood structure at the rear of the lot where more intimate windows and lower ceilings are ideal for private, insulated environments. The more boisterous family spaces move up front, street side. They are large and open, punctuated by the geometry of sculpted forms (cube and a cylinder) that define the big entrance. Large glazing offers a physical and visual connection to the central garden and back to the house’s original façade.

Different approaches were taken for the new and old structures, unified through clean lines, minimal detailing, and a restrained palette of light maple, pale concrete, and white paint. The centenary structure sits on stone foundations while the new extension floats on the soil, supported by piles to avoid damaging the root systems of the trees.