Moisture management for tall wood buildings

Mass timber structures are entering the discussion for many projects in North America, and increasingly for taller buildings. This is, in part, due to recent code changes allowing for combustible construction in taller structures. However, interest in the industry is driven by a larger trend—the need for fast action to mitigate climate change.

For many in the industry, the trend toward taller mass timber structures is exciting. These are the “buildings of the future” that, if designed for low-energy use, can directly contribute to climate change mitigation efforts by reducing both operating and embodied carbon. Additionally, the use of wood in buildings gives designers a direct way to connect occupants to the natural world, and perhaps providing additional motivation for a sustainable future. There are a lot of reasons to feel good about tall wood buildings.

For others, the challenge of constructing tall wood buildings might just be too great. The taller we build, the more uncertainty. Not only does one have to address new design approvals and construction processes, but also there are some basic and pressing questions, such as what happens if the wood burns or if the material gets wet? These are important questions to address.

Fire safety in tall wood buildings

First, the fire question. This article will not deal with fire safety of tall mass timber buildings, but interested parties will see governments, industry groups, researchers, design professionals, and suppliers are all contributing to fire performance assessments, to the planning of integrated fire protection strategies, and to the development of new regulations and guidelines. Many of the challenges are already known—in all tall buildings, design professionals regularly balance the combustibility of building materials, finishes and furnishings, human activities, risk of mechanical failure, etc., with the efficacy of fire protection strategies. These challenges are not unique to tall mass timber buildings.

Moisture and tall wood buildings

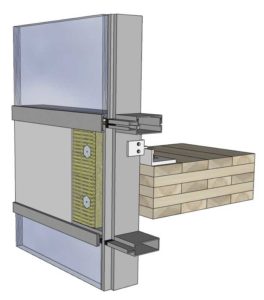

Wood—like many materials we build with—can get wet, but there are limits that designers and specifiers need to be aware of. For example, when wood moisture content rises, there may be dimensional changes that are significant enough to impact adjacent materials and components. Certain types of engineered mass timber components may experience warping or irreversible dimensional changes as moisture content increases. When moisture content is above 19 per cent, the characteristics of the wood elements may change significantly enough to impact structural capacity. This may be a concern at bearing points and where fasteners are located. Above approximately 25 per cent moisture content, moisture may be present in liquid form and allow for progression of decay and fungi and mould growth. Many of these problems are only a concern in tall buildings if high moisture conditions persist, but even short-term exposure can lead to unwanted wetting and associated staining.

In practice, therefore, we want to keep mass timber relatively dry. Components are expected to arrive at the building site at less than 12 per cent moisture content. The goal then is to limit moisture content to below 16 per cent until the building is fully enclosed and the environmental control systems are operating. Designers are encouraged to use these limits as general guides, but it is important to note each species of wood—and each type of engineered wood component—has a different response to moisture. Additionally, the actual moisture content should be expected to change over time in response to changing environmental conditions (See “Changing Moisture Conditions for Mass Timber Elements from Construction to Occupancy”).

In practice, therefore, we want to keep mass timber relatively dry. Components are expected to arrive at the building site at less than 12 per cent moisture content. The goal then is to limit moisture content to below 16 per cent until the building is fully enclosed and the environmental control systems are operating. Designers are encouraged to use these limits as general guides, but it is important to note each species of wood—and each type of engineered wood component—has a different response to moisture. Additionally, the actual moisture content should be expected to change over time in response to changing environmental conditions (See “Changing Moisture Conditions for Mass Timber Elements from Construction to Occupancy”).

Mass timber structures are subject to moisture in the following ways:

∞ Before or during construction:

○ manufacturing;

○ wetting during storage;

○ wetting during transportation; and

○ after erection of the structure and before enclosure.

∞ During operation:

○bulk water leakage through the enclosure (a significant design consideration for tall buildings with higher wind-driven rain loads);

○ accidents (plumbing, sprinklers); and

○ changes to interior environmental conditions (temperature, humidity) and potential accumulation of moisture via air leakage or vapour diffusion.