Masking performance: Zoning in on system design

The specified slider id does not exist.

Compromised tuning

Lastly—but most importantly—if the technician cannot adjust the sound in small local areas, any changes they make to try to improve performance or comfort will affect large areas. While they might be able to resolve a problem in one part of a zone, its sheer size means they are likely to intensify it in another area or create a new issue altogether—and always at unpredictable points across the client’s space. For example, if they need to raise the masking volume to improve effectiveness in one location, it might become too loud in another, decreasing satisfaction. Similarly, if they raise a band level to address a deficiency in one area, it will rise throughout the zone, bringing the sound out of spec in locations where the adjustment was not required initially.

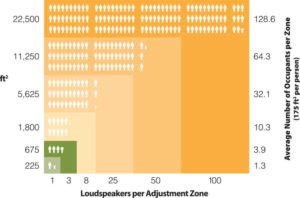

As shown in Figure 1, the larger the zone, the greater the number of people potentially affected by these sound variations. While 21 m2 of space typically accommodates only 1.3 occupants and 63 m2 holds 3.9, if one designs a sound masking system using eight, 25, 50, or 100 loudspeakers in a zone, one is covering 10.3, 32.1, 64.3, or 128.6 people, respectively.

One might try to brush off concerns about seemingly minor volume changes, but their impact is rather significant, even without taking frequency into consideration. Users can typically expect a 10 per cent reduction in performance for each decibel drop in the masking volume. So, while an occupant might only be able to understand 30 per cent of a conversation with the masking set to 48 dBA, they might comprehend more than 70 per cent at 44 dBA. The typical specification for larger zoned systems is ±2 dBA (i.e. plus or minus two A-weighted decibels), giving a range of 4 dBA overall, despite a technician’s best efforts to accurately tune the sound. An even more poorly designed masking system can allow as much as a ±3 dBA variation, or 6 dBA overall.

To be consistently effective, masking volume should vary no more than ±0.5 dBA at test points across the entire installation, except in circumstances well beyond the technician’s ability to control (e.g. HVAC). A sound masking system designed with zones no larger than three loudspeakers—each offering fine control over volume and frequency—can achieve these results, providing the zones are tuned individually.

Can the performance deficiencies of large zones be overcome by, for example, installing the loudspeakers facing downwards? If ‘near-field’ measurements are taken a couple of inches below each loudspeaker, a technician might conclude they have achieved consistent results. However, if masking sound is measured at ear height—where occupants actually experience its effects—the findings will be different. For example, one recent acoustic study of an installation using downward-facing or ‘direct-field’ loudspeakers found 3 to 4 dBA differences at ear height between two offices, whereas the output at the loudspeaker was nearly identical.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, the client is paying for the effect, not the sound masking equipment. To deliver value rather than simply introducing a random amount of background noise to a facility, professional integrators need to accurately achieve the specified masking spectrum throughout the installation. The smaller the zones, the more test and adjustment points the design offers the technician. The more precise the masking sound, the better the outcome for the client.

Niklas Moeller is vice-president of KR Moeller Associates, manufacturer of LogiSon Acoustic Network and Modio Guestroom Acoustic Control. He has more than 25 years of experience in the sound masking field. He can be reached at nmoeller@logison.com.

Niklas Moeller is vice-president of KR Moeller Associates, manufacturer of LogiSon Acoustic Network and Modio Guestroom Acoustic Control. He has more than 25 years of experience in the sound masking field. He can be reached at nmoeller@logison.com.