Making a case for sprayfoam in the unvented attic

History of unvented attics and relation to building codes

Some of the first instances of the strategy in actual practice took place in the late 1980s. One Canadian municipality, reporting to an assembly of building officials from large municipalities, noted no early deterioration of roofing materials in its experience with the strategy, spanning some 15 years. (This information is derived from the Toronto Area Building Inspectors Committee [TABIC] Minutes from March 2006.) At this time, it is likely each installation was the subject of a unique building department review and approval, as these would have predated the advent of ‘objective-based’ codes.

The intent of attic space ventilation is to remove unwanted moisture. However, as the Appendix Notes to Section 9.19.1 of the 2015 NBC still point out, for constructions that are sufficiently airtight, the required ventilation may be omitted if it can be shown to be unnecessary. It is interesting to note this language has, with little to no modification, carried on to the present day. To take advantage of the exception now, an application for an alternative solution would typically be presented to the building official.

Even in 1993, research summaries suggested no strong correlation existed between ventilation rates, the location of vents, and moisture content of wood members. (For more, consult “Attic Ventilation and Moisture,” part of Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s [CMHC’s] Technical Series 92-201, Research and Development Highlights.) As part of the same study, high ventilation rates in a marine climate were reported to actually result in higher roof sheathing moisture contents. More building researchers began studying and writing about the topic.

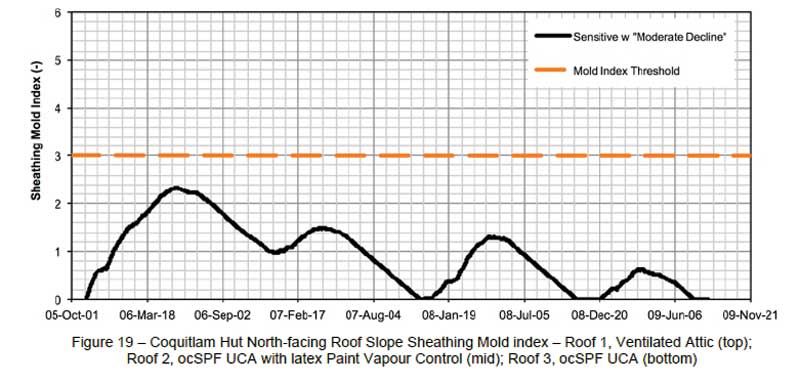

In general, the primary durability concern for unvented attic designs has been the sheathing moisture content and its potential for mould growth throughout the seasons. Approximately 20 per cent moisture content is generally considered a safe level. Contents between 20 and 28 per cent are cautionary, as wood decay can continue following the onset of the process.

Some studies have gone further, using the temperature of a substrate and relative humidity (RH) to calculate a ‘mould index.’ First developed at the VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland and the Fraunhofer Institute, the index is consistent with current consensus standards for moisture design, such as American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) 160, Criteria for Moisture-control Design Analysis in Buildings. For wood materials, a rating of no greater than ‘3’ is generally considered acceptable. This would correspond to a coverage of less than 10 per cent visually, and less than 50 per cent under a microscope.