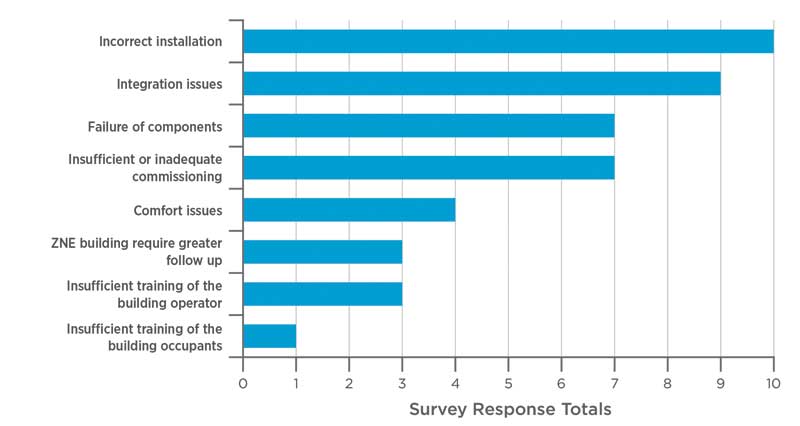

Lessons learned about zero-net-energy buildings

Images courtesy CABA

Understanding building controls

Definitions abound in the use of terms within any discussion of the built environment. The CABA/NBI study manuscript cites the zero-net-energy building as having “greatly reduced energy loads such that, over a year, 100 per cent of the building’s annual energy use can be met with onsite renewable energy.” Especially in Canada, where winters require heating and summers often requiring cooling, this can be difficult to achieve, given the country’s desire for glass surfaces that are frequently thermally inefficient. Fortunately, operable building controls can help.

Manual controls

Certainly, manual controls are the simplest and most economical to implement. Their effectiveness would depend on the design, including how much of their operations is intuitive and present without a user intervention. Switches would need to be accessible and convenient for occupants to use. A motivated user base would have a higher level of success.

Drawbacks are manual-based systems are subject to actions of individuals based on their proximity and personal preferences versus actual need. Manual systems are also difficult to model in energy-usage programs and to assign values for use in analysis for green building rating systems.

Automated controls

Automated systems are reliable, repeatable, and effective. At its simplest, a basic thermostat adjusts heating and cooling based on the desired setting and a sensor determining the need to activate the system. There are many different systems and their strategies differ. Building management or automation systems (BMS or BAS) are, as their name implies, for the whole building. Typically, schedules provide information on expected usage and pre-determined settings provide information on heating, cooling, elevator usage, security, and lighting. The scope of control is determined by a building design team, informed by meeting codes and standards being followed.

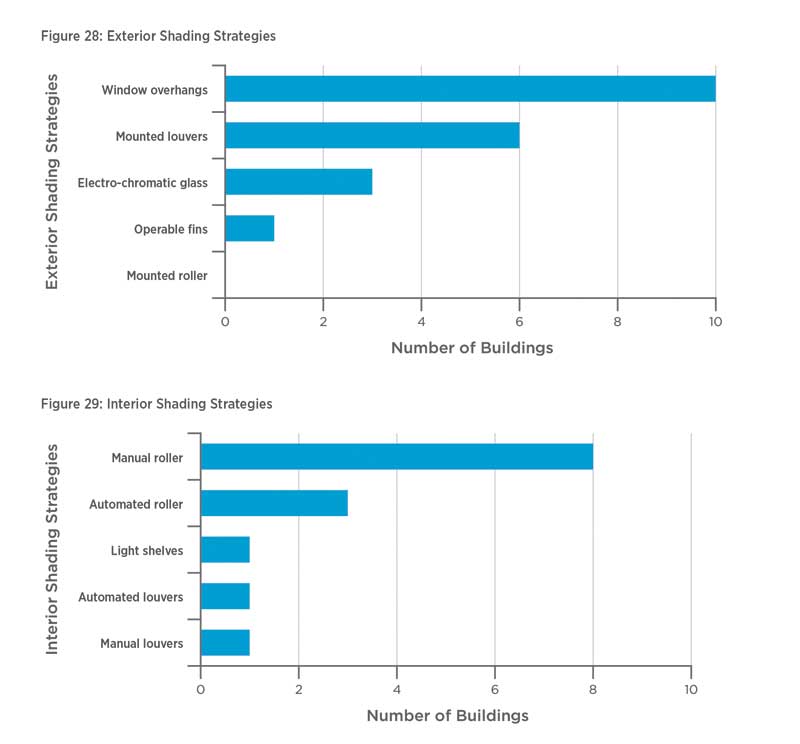

Specialized systems can also be employed, such as automated shading control systems for operation of shades and window treatments to manage glare and reduce heat gain, as well as to preserve a view to outside by bringing shades up when direct sunlight is not on one elevation. Automated lighting control systems can respond to daylight being present in a space by turning off or dimming lighting nearest the window.

Comprehensive systems can:

- turn off HVAC units or change temperature levels;

- turn off lighting or reduce fan motors in response to time-of-day conditions; and

- fluctuate electrical power rates or provide demand response to meet needs of utilities to reduce power consumption.

Therefore, computers tracking the information then activate the appropriate system. Computerized operations also allow for recording of events and energy consumption—both of which are useful for later detailed analysis of loads and for providing information for the energy consumption dashboards frequently seen with large buildings.

The design of any automated system should include careful matching of zones with the building elements and the space’s architectural program. Both an adequate number and type of sensors to be used will provide actionable information to a system. As critical to a control system as is the calendar, sensors can be hard-wired or wireless, utilizing one of the many different communications platforms available.

In the lighting arena, sensors are offered for occupancy as well as vacancy. Careful analysis is required for optimal performance. The design strategy should be thoroughly explained to users so operation is understood by all as essential to meeting sustainability goals.