Innovations and insulated metal

By Peter Macnab, B.Arch., CSC, MRAIC

Thermal efficiency is fast becoming the focus of the next stage of exterior wall development throughout Canada. Ontario, in particular, arguably now has the most stringent code requirements in North America when it comes to energy conservation.

Not only will this new focus affect architects and specifiers, but it is having a huge impact on building product manufacturers in the country, because the Ontario Building Code (OBC) has adopted American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) 90.1-2010, Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-rise Residential Buildings, as modified by OBC SB-10. This supplementary updates require new buildings to exceed the 1997 National Building Code of Canada (NBC) by 25 per cent.

For those not using energy modelling to achieve the performance levels, prescriptive paths are required. This involves a modified implementation of ASHRAE 90.1-2010 with ASHRAE 189-2009, Standard for the Design of High-performance Green Buildings. The new code places particular emphasis on a requirement for continuous insulation (ci) and the elimination of thermal bridging in wall systems. A thermal bridge is a fundamental of heat transfer where a penetration of the insulation layer by a highly conductive or non-insulating material takes place in the separation between the interior and exterior environments of a building assembly.

Other jurisdictions in Canada are now expected to follow Ontario’s lead. As a result, traditional cladding systems—including metal building assemblies that employ multisystem components, metal Z–girts in particular—will not meet the new code requirements. In effect, this is because the Z-girt allows for thermal bridging.

In Canada, a number of clip solutions have been introduced that can help eliminate the thermal bridge, but they add to both the system’s complexity and cost. What other solutions are out there?

Evolution of the envelope

Looking back from the perspective of envelope evolution, the building exterior historically acted primarily as a barrier between the interior and exterior environments, yet was also meant to be esthetically pleasing to the eye. This primary function has remained central throughout time. In the early 1900s, newly created technology in sheet metal, driven by mass production of the automobile, paved the way for developments in metal building and wall construction. During the last 30 years, there have been not only modern metal wall systems (e.g. aluminum plate and metal composite panels) but also masonry, precast concrete, glass curtain wall, and exterior insulation and finish system (EIFS) façades.

Typical wall systems now comprise a masonry or metal stud and drywall backup (with an applied air vapour membrane). The Z-girts are installed and then the insulation is applied to the air vapour barrier. Finally the cladding, which might be steel, aluminum plate, or metal composite panels, is fastened to the Z-girts. Some of the newer panel systems include fibre cement, ceramic, and wood composite options. A great deal of research and development over the years has gone into minimizing air and water infiltration into the building interior by equalizing wind pressures with all these exterior wall systems. The end result is the pressure-equalized rainscreen (PER) has become an effective performance-driven method of keeping interiors dry.

The widely specified system is essentially an effective multi-line of defense to air and rain infiltration. What makes it unique is the exterior wall system skin is vented to pressure-equalize the cavity. However, as effective as it is at keeping air and water out of the building’s interior, it unfortunately does not meet the new ASHRAE

90.1 requirements.

Success with IMPs

Insulated metal panels (IMPs) have a successful track record in North America, having been originally developed for cold storage usage in above-average thermal resistance environments. Ironically, these systems were initially developed as far back as the 1970s, but due to the popularity of metal composite panels and the availability of inexpensive energy, they were before their time.

The IMP system comprises two sheets of steel, usually 26-gauge, sandwiching a foamed-in-place core of closed cell polyisocyanurate (polyiso) insulation, achieving R-7.7 per inch in some systems. This offers the highest R-value of any system on the market per inch. Further, IMPs can be removed and reused in other projects; the steel is fully recyclable.

The IMP system comprises two sheets of steel, usually 26-gauge, sandwiching a foamed-in-place core of closed cell polyisocyanurate (polyiso) insulation, achieving R-7.7 per inch in some systems. This offers the highest R-value of any system on the market per inch. Further, IMPs can be removed and reused in other projects; the steel is fully recyclable.

With a continuous process, there is little or no variation of R-value due to long-term aging. Other processes that would include the use of polyiso or polyurethane stockboard will have a long-term thermal resistance (LTTR) value

because the blowing agent escapes from the foam cells. With a metal-faced continuous IMP product, the face of the panels are impermeable and do not allow for the escaping of the blowing agent (and consequently, the R-value reduction). There is some loss, at the panel ends, but minimal.

These panels’ typical double-tongue-and-groove joinery, with concealed fasteners, eliminates unwanted thermal bridging. The system acts as a complete air barrier, preventing any moisture from entering the building, and also eliminating the necessity of an air/vapour barrier membrane.

IMPs are monolithic historically, which has relied on gaskets and caulking to keep air and water out. In other words, they traditionally have required a lot of maintenance to replace worn-out gaskets and caulking. These assemblies do not have any exposed fasteners or caulking. Additionally, the interior joint of their double-tongue is sealed to allow for a continuous air vapor barrier; it is shipped to a jobsite ready for quick and easy installation.

Using IMPs is like wrapping a thermal blanket around the structure of a building. As these wall panels are typically 76 mm (3 in.) thick (i.e. R-24), and 1 m (1/3 ft) wide by up to 15 m (50 ft) long, they can be installed in a fraction of the time it takes for more archaic systems with many components to install. They provide the potential for constructing a building in Canada during the winter while being able to enclose the building quickly so workers can comfortably get to the interior finishes with the inside heat on.

Design vision and flexibility

IMPs can work harmoniously to integrate with other building materials, or may be utilized as a complete wall system in cold storage and industrial applications where the interior liner side is exposed to the interior of the building. All this maximizes the architect’s design freedom.

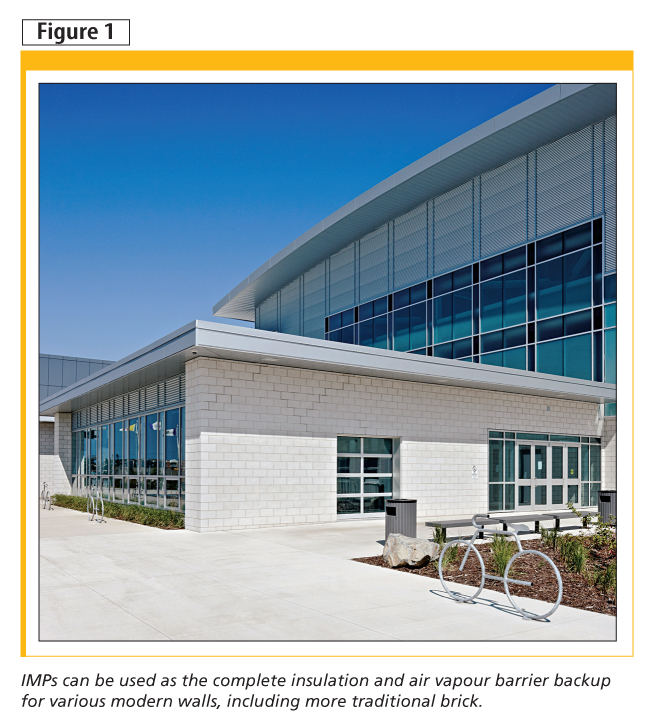

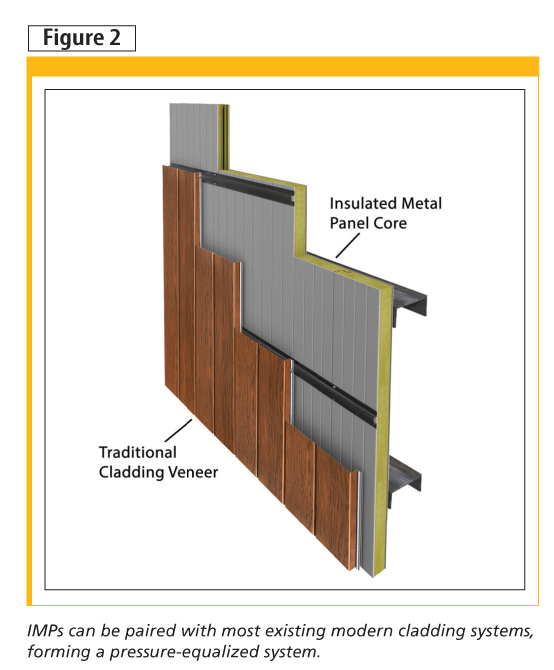

Insulated metal panels can be used as the complete insulation and air vapour barrier backup for various modern walls, including more traditional assemblies such as brick (Figure 1). In commercial and institutional applications, the full visual variety of vertical and horizontal cladding options can be attached to the IMP (Figure 2). Essentially, this involves the marriage of IMPs with most any other existing modern cladding systems, forming a pressure-equalized system, and the highest R-value per inch.

When specified as the finished product itself, IMPs have evolved from a utilitarian freezer-type panel to a much more sophisticated look that can be implemented in an even broader range of building forms. It continues to metamorphose, offering new styles ranging from sleek, high-tech avant-garde metallic appearances all the way to a more traditional, old-world stucco-textured finishes.

While many other panel systems tend to be square or modular, metal panels can be linear—offering a visual effect that can be used to enhance architectural design. In the project shown in the first photo, IMP panels were used horizontally in long lengths to emphasize the linear esthetic of the building, as well as using a stucco-like appearance to give a warm feeling to the façade.

Conclusion

In Canada, IMPs still account for less than five per cent of exterior metal walls. This could change rapidly with the adoption of ASHRAE-90.1, however, not only in Ontario, but throughout the rest of the country. Sweden, Australia, Switzerland, Denmark, and Norway all prioritize environmental policies, energy use, energy sources, risk mitigation, and biodiversity—consequently, they have stringent energy codes. In most of these countries and others, like Germany and the United Kingdom, IMP systems now account for half of the metal panels market share.

Sometimes the need for change leads to innovation, in which ordinary ideas are brought together to create something exceptional. Beyond being products or proprietary inventions, the most successful innovations are platforms with bigger ambitions. Insulated metal panel wall systems could become a viable solution, supporting both the functional and esthetic needs of Canadian design/construction professionals and building owners.

Peter Macnab, B.Arch., CSC, MRAIC, is the marketing development manager for Vicwest. He has 30 years of experience in the building design and product world, primarily in the Atlantic provinces. A trained economist and architect, Macnab has been with Vicwest for more than 15 years, working as a design team associate on multi-residential award-winning design projects and as a sales manager for exterior building systems. He lives in a home he designed on St. Margaret’s Bay, Nova Scotia. He can be reached at pmacnab@vicwest.com.

Peter Macnab, B.Arch., CSC, MRAIC, is the marketing development manager for Vicwest. He has 30 years of experience in the building design and product world, primarily in the Atlantic provinces. A trained economist and architect, Macnab has been with Vicwest for more than 15 years, working as a design team associate on multi-residential award-winning design projects and as a sales manager for exterior building systems. He lives in a home he designed on St. Margaret’s Bay, Nova Scotia. He can be reached at pmacnab@vicwest.com.