High or Low-e? Low-emissivity coated glass for apartment buildings

By George Torok, C.E.T., BSSO

In many large, urban areas of Canada, most of the population lives in apartment buildings. In the downtown core of cities like Toronto, the proportion is up to 70 per cent. With the current trend to intensify urban areas to limit sprawl into surrounding valuable farmland, the proportion of high-rise multi-family dwellers is expected to increase.

Building owners, operators, and residents in apartment buildings often report thermal discomfort in the fall and, especially, spring. This is due to the degree of solar radiation exposure, which is highest in these seasons due to a combination of low altitude and narrow azimuth range that causes the sun’s rays to be closer to normal (perpendicular) to the face of window glass (low angle of incidence). This results in maximum transmission to the building interior.

The angle of incidence is increasing in the spring and solar energy transmission is therefore falling, but the discomfort is often worse than in the fall because daytime hours are also on the rise. Additionally, outdoor temperatures are typically colder so windows and exterior doors are closed to keep out cold winter air.

Understanding the problem

Apartments with sunny exposures need space heating turned off early in the spring and turned on late in the fall; apartments with less exposure need space heating turned off later in the spring and turned on earlier in the fall. Typically, space heating systems are not zoned, with residents often having only limited control over space heating to compensate for solar radiation gain in condos and apartments with high solar gain.

When provided, cooling systems cannot always operate at the same time as space heating to provide relief. The thermal comfort of apartment residents suffers, as does the sanity of building owners and operators. Residents may try to cope by venting excess heat through open doors and windows or reducing solar gain by covering windows with curtains, blinds, shades, or aluminum foil. An apartment building with many covered windows during a sunny day is often indicative of a solar gain problem.

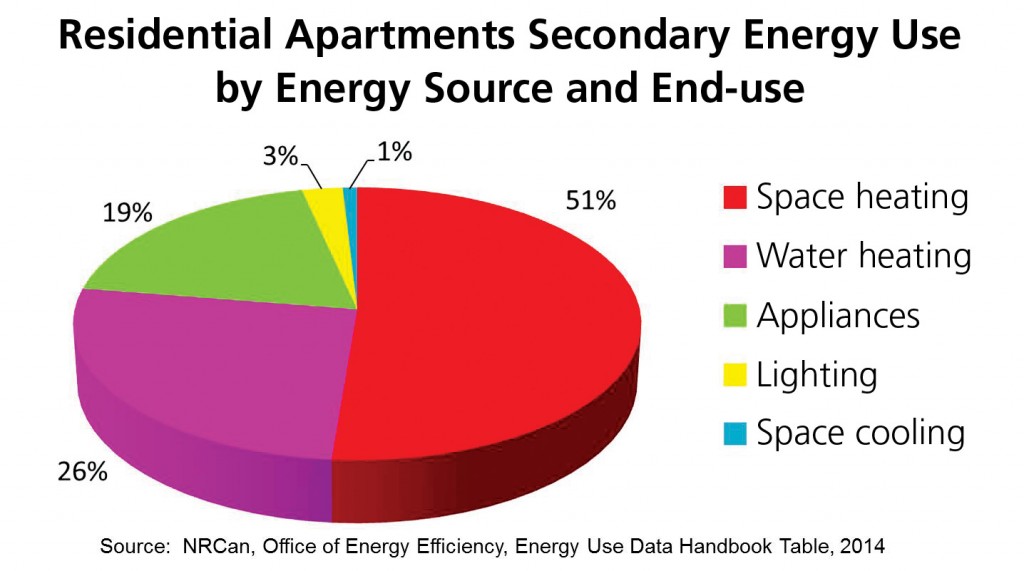

Energy use in residential apartment buildings accounts for 16 per cent of total energy used by Canadians and about 14 per cent of overall greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Space heating accounts for 51 per cent of residential energy use. Despite a 30 per cent increase in Canadian high-rise apartment households and condos in the current construction boom, the rate of growth of heating energy consumption has been modest—only about two per cent. This reflects the increased energy efficiency requirements in building codes (Figure 1).

Global warming, giving rise to milder winter temperatures in many locations, has also helped reduce space heating demand. However, it likely adds to space cooling demand; while space cooling energy usage is low, it is increasing rapidly—about 43 per cent in the same period. This also mirrors the increasing use of highly glazed building enclosures—window walls—that allow much more solar gain than traditional designs.