Going green with geothermal: What every developer needs to know

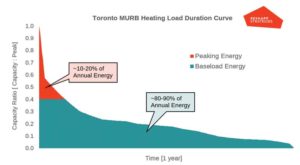

Additionally, hybrid systems can act as a backup to the geothermal system, if needed, although the latter is more reliable than a conventional plant. For example, if the system is set up with the proportions described above, there will be a conventional assembly capable of handling at least 95 per cent of the season’s capacity and offer reassurance, if there is any worry about the geothermal system’s performance.

The use of hybrid equipment, particularly a boiler, can provide the ability to run high temperatures at certain times, whereas a full geothermal system can operate only at ‘ambient’ temperatures. The geothermal loop ambient temperatures can approach freezing levels in the winter, and that, in turn, means a big step up in temperatures required for effective heating. When this delta is large, heat pumps need to work harder and, therefore, need to be sized larger to deal with this ‘de-rating.’ This can mean heat pumps cost more and use more space in floor plans. The use of a boiler deals with de-rating by running the water loops at higher temperatures on the coldest days of the year, also known as design days, and help avoid oversized heat pumps.

Time constraints are another consideration for developers when installing a geothermal system, which can often lie on the critical path. In this case, a hybrid system, which inherently requires less drilling than a full one, will take less time to drill. This is an important factor when considering the ‘time value of money’ most developers are focused on. Further, because hybrid systems require fewer boreholes, they are often the only option if the site is small and cannot fit a field big enough for the entire building load.

Photos © BigStockPhoto.com

Going with a hybrid system does not entirely eliminate natural gas consumption onsite, leaving some exposure to natural gas that a full geothermal plant would eliminate. However, if 80 per cent of the energy is coming from the geothermal field, the system is 80 per cent future-proofed and is 20 per cent ‘unhedged’ against any rise in natural gas prices or other potential legislation prohibiting gas use.

The other disadvantage with a hybrid system is it still requires the mechanical space of a full conventional plant. This is where site-specific factors might cause people to reconsider the optimal geothermal-conventional mix. If the mechanical space can be repurposed into useful floor area, it may be more economical to build a larger geothermal field. In markets like Toronto and Vancouver, a few thousand square feet of mechanical space recovered can amount to some million dollars.

Going 100 per cent geothermal may not be needed to achieve the goal of maximizing a building’s sale value. For example, the geothermal field could be sized large enough to eliminate a cooling tower that might reduce a mechanical penthouse height to allow for an extra floor, while still being hybrid on the heating side.

Setting up the air side

Geothermal heating and cooling systems can work with any type of hydronic in-suite equipment, whether or not fan coils, heat pumps, or even variable refrigerant flow (VRF) are preferred.

Although fan coils are likely the least expensive in-suite equipment, they are often not a good choice for interfacing with a geothermal loop. Two-pipe fan coil systems cannot ‘load share,’ which is a convenient way to improve efficiency in the shoulder seasons by matching co-incident heating and cooling loads in the building. A fan coil configuration will also require large, centralized, water-to-water heat pumps that are expensive and take up mechanical space, usually sub-grade.

This usually makes fan coils a less attractive option to in-suite heat pumps, which can do the same work on a distributed basis and eliminate the need for centralized water-to-water heat pumps. The drawback with this setup is the noise associated with heat pumps, although this is less of a factor if the units are small (1.5 tonnes or less seems to be acceptable).

A VRF configuration works similar to in-suite heat pumps, but tends to be more efficient as no heat pump compressor energy is needed to load share. It also deals with the noise issue by having a single heat pump in a central mechanical closet on each floor that is away from the living spaces. Additionally, VRF has the potential to save on distribution piping costs needing only one set of risers versus one for every two units per floor that are more typical in a heat pump or fan coil design. On a tall tower, this can be a significant sum.