Glass claddings for tall buildings

By Patrick Marquis, Brenda McCabe, PhD, P.Eng., FASCE, and Arash Shahi, PhD, P.Eng., PMP

A dramatic increase in the demand for and construction of tall buildings in Toronto has resulted in the city producing the highest per capita number of residential towers in North America. (This comes from Emporis’ 2014 release, “High-rise Construction in North America: Toronto Continues to Lead Going into 2014.” Visit www.emporis.com/press/press-release/1/high-rise-construction-in-north-america-toronto-continues-to-lead-going-into-2014.) Before 2000, 90 per cent of existing buildings taller than 150 m (492 ft) were commercial structures. In recent years, the paradigm has shifted—now 90 per cent of newly constructed towers over that height are used as residential property. (For more, see the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat [CTBUH]’s “Year Review for 2014,” published in International Journal on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat [1, 44-48].)

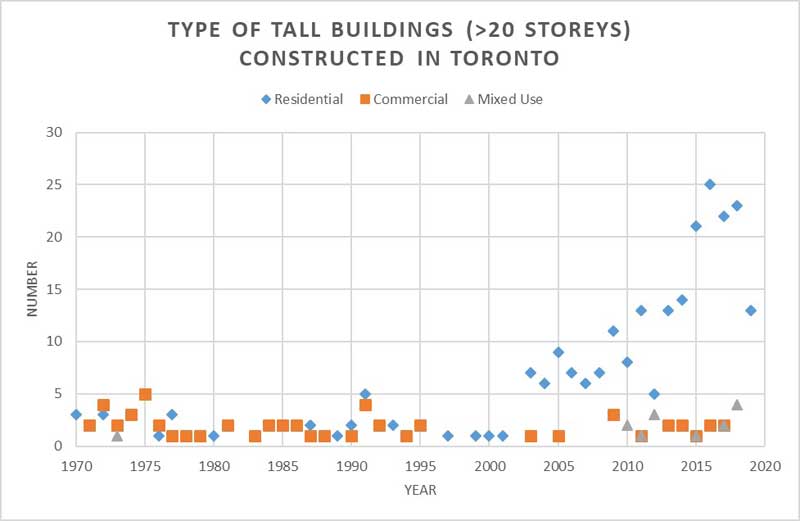

Using the University of Toronto’s (U of T’s) Building Tall Research Centre’s database, Figure 1 shows a visual representation of the city’s exponential growth of tall residential towers, including those scheduled for completion in 2018 and 2019. (The Building Tall Research Centre conducts and promotes research related to tall buildings from multidisciplinary technical perspectives. The group collaborates with designers, consultants, developers, builders, and policy-makers.) The increasing urbanization and high-density urban areas help provide affordable living, facilitate efficient supply of services, and further efforts to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Images courtesy Building Tall Research Centre

High-rise residential buildings in Ontario follow the same codes and standards as commercial buildings, even though they have very different uses and contexts. As policy-makers continue to improve the standard for energy efficiency in buildings, it may be important to consider the context of an occupant in a high-rise residence separately from a commercial building workplace.

Window wall versus curtain wall

The enclosure designs for these modern tall buildings in Canada often incorporate highly glazed cladding systems such as the window wall and curtain wall (Figure 2). There have been varied concerns about these assemblies, such as energy performance, lifespan, reliability, and resilience. However, not all design/construction professionals truly understand the difference between the curtain wall and window wall.

When discussing curtain walls and window walls, much of the attention is on the performance of the window or insulated glazing unit (IGU). However, both systems can employ the same IGUs, whether poor-performing windows or high-performing triple-glazed units with low-emissivity (low-e) coatings. Where the systems differ is how they attach to the structure. Simply put, the main difference is the window wall structurally sits between the suspended reinforced concrete slabs while the curtain wall is hung off the slab edges by anchors.

However, there are many more intricacies differentiating the systems. The curtain wall is esthetically slick, modern, and desirable for many architects. It is used primarily for commercial buildings, and some unique residential projects. Curtain walls are structurally engineered and typically installed from the outside using a crane or a rig, which make them more expensive and more rigorous to install than window walls, which are put up from the building interior.

In early versions of window walls, there was a break at every floor, detracting from their sleek continuity. Modern systems, though, make it possible to closely mimic the esthetic look of a curtain wall. Window walls are almost exclusively used in residential buildings since they provide a practical and cost-effective method to install highly glazed cladding, while still allowing balconies and operable windows—this feature is rarely offered with curtain wall designs.

The two cladding systems are used in different situations; a thorough and objective performance comparison has been made in a recent U of T report that recommends their best use and possible improvements. (The report in question, by this article’s three authors and H. Ali, F. Mirahadi, R. Lyall, and P. De Berardis, was presented at the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering/Construction Research Congress [CSCE/CRC] International Construction Specialty Conference in Vancouver earlier this year. Entitled “Window Wall and Curtain Wall: An Objective Review,” it is available at buildingtall.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Marquis_P_et_al_CON125_Window_Wall_Curtain_Wall.pdf.) Three key findings from the report include:

1. The window wall is the more suitable application for residential construction.

For residential applications, window walls better accommodate features such as balconies, operable windows, and suite compartmentalization (i.e. containing odours, noise, and air movement within a single unit). These assemblies also offer significant advantages over curtain walls for constructability, cost, and maintenance.

2. Curtain walls have certain advantages in the metrics of thermal performance, airtightness, and water penetration.

Intrinsic properties of curtain wall and the way it is attached to the structure give it advantages in the performance areas listed above. However, the review shows a well-designed and properly installed window wall system can perform equal to or better than a typical curtain wall based on these metrics, and at a lower cost.

3. Best practices for the design and installation of window wall cladding systems have advanced to achieve better performance.

This improved performance includes reduced thermal bridging to the concrete structure, less conductive window-wall frames, and use of a rainscreen design to collect and drain any penetrating water.

Construction mockups and field testing have become commonplace and further contribute to improving water penetration and air infiltration.

The window wall has substantially evolved since it first appeared. Many of the perceived faults are attributed to its older iterations, such as the lack of slab covers. With the new design features and technological advances, the window wall can be a good alternative to the more expensive curtain wall, even for commercial buildings. Considering its advantages for operable windows, balconies, odour and sound isolation, and cost, a well-designed and well-installed window wall is the most suitable choice for tall multi-unit residential buildings (MURBS).

While the differences between the systems have been well established and potential improvements suggested, a common concern for both the curtain wall and window wall still exists for many building scientists—the large window-to-wall ratios (WWR) that typically come with them.