Facade design: The benefits of early-stage energy modelling

Accepting uncertainty

All predictive models come with limitations, and it is important to consider these in relation to the intended use. The model described in this article hinges on several assumptions about the physical world. It assumes no thermal storage is occurring in the building materials, and, consequently, exaggerates the heating load. Moreover, the model does not consider transmitted solar radiation; only the fraction absorbed by the glazing. Internal heat gains, from people, lights, and equipment, are also missing. These exclusions lead the model to overestimate heating demand. Most notably, the model does not include heat losses through the ground and roof, as it only models a room on the middle floor of a building.

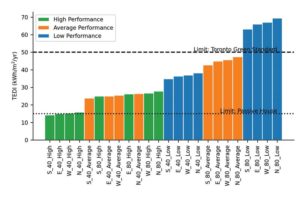

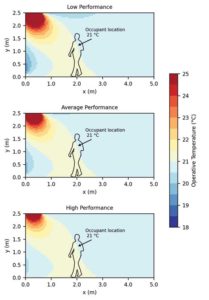

Given these limitations, the model is not suitable for proving the overall design of a building which meets a certain energy target or complies with a certain standard. For example, the model would not be able to prove a design which complies with Part 8 of the NECB. This is a task for comprehensive whole-building energy modelling software. Rather than competing for this scope, the model described here introduces energy modelling to the earliest stages of a project, where typically none would occur. During these stages, the “overall design” may be no more than a napkin sketch; therefore, the model’s simple inputs are its strength. With some basic geometries, thermal properties, and a weather file, the architect can compare, in relative terms, how various facade designs affect heating load/demand (e.g. option A is 50 per cent better than option B). Further, the model can give insight as to whether a design puts the building within the ballpark of a TEDI or peak heating load target. These insights are delivered rapidly by the Python script, which means an architect can iterate the facade to converge on an energy target. The benefit of performing these studies early is that costly changes to the wall thickness, glazing ratio, etc., can be avoided later in the design process.

The concept of using simulation to shape early-stage design is not new, nor is it unique to this example. For more than five years, the industry has seen the emergence of many cloud-based tools for assessing energy, daylight, and wind. Some of these are built on top of well-known simulation engines, while others are built from scratch. Both share an objective of increasing the role of simulation in building design by making the process quicker and more accessible to non-experts. While these tools have yet to become the norm in everyday practice, they promise to boost design efficiency in the future.

Notes

1 DOE. (2021). Input Output Reference. In DOE, EnergyPlus Version 9.6.0 Documentation. U.S. Department of Energy.

2 Feist, W., Bastian, Z., Ebel, W., Gollwitzer, E., Grove-Smith, Jessica, . . . Steiger, J. (2015). “Passive House Planning Package Version 9.” Darmstadt: Passive House Institute.

3 Graham, J., Turnbull, G., Constable, D., Reimer, M., & Vanwyck, J. (2022). “Modelling Perimeter Heating Demand: A Function of Occupant Thermal Comfort.” Facade Tectonics World Congress. Los Angeles: Facade Tectonics Institute. Retrieved from www.facadetectonics.org/papers/modelling-perimeter-thermal-energy.

4 Huizenga, C., Zhang, H., Mattelaer, P., Yu, T., Arens, E., & Lyons, P. (2005). “Window Performance for Human Thermal Comfort – Final Report.” Berkeley: Center for the Built Environment.

5 Tredre, B. E. (1964). “Assessment of mean radiant temperature in indoor environments.” British Journal of Industrial Medicine, 22, 58-66.

After graduating from Toronto Metropolitan University with a master’s degree in building science, Jonathan Graham joined KPMB Architects with a mission to help architects prioritize energy efficiency, carbon reductions, and occupant comfort in their design decisions. As an analyst with KPMB LAB, the research and innovation group at the firm, he specializes in using building performance simulation to test and rationalize sustainable strategies. He has conducted varied research on sustainable solutions for the architectural design process, and co-authored peer-reviewed journal publications about urban microclimate, solar photovoltaics, and thermal comfort modelling.

A certified Passive House designer, Graham leverages his expertise in building science and programming to create custom tools tailored to each design question.