Exploring the balancing act of glass in construction

by Elizabeth Cotton

Glass has the capacity to be part of beautifully designed buildings, to make a statement, and to allow for dramatic views of the outside from within. It can be specified to add a sense of lightness to a structure as well as to convey a modern, impressive, and eye-catching look. At the same time, it must meet the project’s performance requirement because of today’s focus on sustainability and energy efficiency.

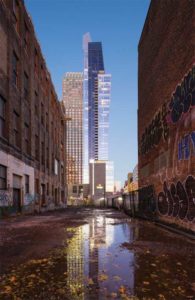

Glass has the potential to meet both the performance and esthetic needs of a project as it is not only attractive, but also energy-efficient. Therefore, it is often used in Canada’s urban centres where new multifamily residences and office buildings are being constructed at an accelerated pace to fulfil demand for space.

“Multifamily/condo towers are the most rapidly growing segment,” says Calin Caliman, associate/manager, architecture, IBI. “At our firm, I would say these structures comprise 90 per cent of our work due to the demographics.”

Residential towers tend to be glass-heavy in design because tenants want ample light and a feeling of more space. Office buildings are crafted with large windows due to an increased focus on wellness in the workplace—access to daylight is key to employee well-being and contentment.

Meeting standards across the country

Canada has many different green building standards at national, provincial, and city levels. One of the most well-known rating systems is Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED). Criteria for LEED certification include focusing on sustainable site development, water savings, overall energy efficiency, the selection of materials for energy-saving purposes, and the promotion of indoor environmental quality.

Additionally, the Canadian Green Building Council (CaGBC) developed the Zero Carbon Building Standard to enable the country to support the objective of “eliminating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with the operation of new buildings by 2030, and eliminating GHG emissions from all buildings by 2050.”

CaGBC deems a zero-carbon building to be one that “is highly energy-efficient and produces onsite, or procures, carbon-free renewable energy in an amount sufficient to offset the annual carbon emissions associated with operations.”

For a more specific building segment, the Green Key eco-rating program offers recognition to hotels, motels, and resorts striving to improve environmental and cost performances. The property goes through an audit specific to its energy consumption, and then is awarded a key rating—the higher the rating, the more efficient the structure—that can then be used to ‘unlock’ incentives. These incentives include opportunities to reduce a property’s costs and environmental impacts by lowering energy consumption, training employees, and improving supply chains.

On a more local level, cities themselves have similar initiatives. One example is the Toronto Green Standard (TGS) with sustainable design guidelines for new private or city-owned buildings. Originally introduced to address environmental issues in Toronto, TGS is a performance-based standard, meaning third-party prequalified consultants monitor the energy usage of the facility in order to ensure compliance. In terms of glass in buildings, designers are required to use low-reflectance or opaque glass, put markers on the glass, or integrate structures into the building to diminish reflection on 85 per cent of all exterior glazing within the greater of the first 12 m (36 ft) of the building above grade or at the height of the mature tree canopy. This is to ensure bird-friendly glazing is applied to the building. In some cases, this move can have the added bonus of conserving energy because opaque glass traps heat, beneficial to a building in the winter. Other effects can be achieved with the right kind of low-emissivity (low-e) coating on specific surfaces of clear glass assembled in an insulated glass unit (IGU).

Emissivity is the ability of a material to radiate energy. When energy from light or heat is absorbed by glass, it is either pulled away from the material by moving air, or reflected back into or outside a space. Special, microscopically thin coatings of silver for ‘soft-coat’ glass or tin oxides for ‘hard-coat’ glass can help with temperature regulation, reflecting heat away from the glass or absorbing it. These low-e coatings also enable the windows to emit less heat. By reducing the amount of heat a window emits, its thermal performance can be improved. This result in a better insulated building, as warm air is either kept inside, thereby decreasing heating costs, or heat is reflected away from the building, leaving the interiors cooler.