Designing workplaces to minimize noise and sound impact

Sound versus noise

To move forward, one must first address what is perhaps the most pervasive source of confusion in architectural acoustics: misuse of the terms “sound” and “noise.”12

Although these words are often used interchangeably—as are “ambient sound” and “ambient noise”—“sound” refers to acoustic waves (or, in the case of occupants, the transportation of physical vibrations in the air within the human ear’s frequency range of 20 to 20,000 Hz), while “noise” is essentially “unwanted and/or harmful sound” or, in Kryter’s words, “audible acoustic energy…that is unwanted because it has adverse auditory and nonauditory physiological or psychological effects on people.”13

The classification of some types of sounds as “unwanted” is key to achieving “good acoustics.” Many studies into non-auditory health effects consider noise emitted by industrial and environmental sources, as well as transportation (e.g. road, rail, and airplane traffic); however, in spaces with higher occupant densities such as offices, occupant-generated noise is the most significant cause of acoustical dissatisfaction. Traditional assessment methods seldom make provisions for this source (focusing on building-related systems, services, and utilities) and, because of its complex nature, building professionals are not easily able to account for it during design—that is, unless they put sound to work.

Sound is also continuously produced and present in the built and natural environment—by the individual and those around them, office equipment, and the essential building systems, services, and utilities that support other environmental parameters within the space—and it also enters from the outdoors.

This understanding—that everyone is constantly surrounded by acoustic energy—helps in exploring more nuanced acoustical concepts, such as the “audibility” of sound and its beneficial uses (i.e. how it can be leveraged to support occupant needs?), and not only the adverse effects of noise.

The Masking Effect

As an example, imagine a room sufficiently well insulated to prevent noise transmission, allowing one to solely focus on the interior ambient conditions. Occupancy is limited to one person. The resulting space is one in which the overall background sound level is exceptionally low. Now imagine what this space may or may not sound like. Most would describe it as “silent.” In practice, environments designed to meet this extreme criteria are highly specialized acoustical facilities (anechoic chambers), and occupants often describe their experience as uncomfortable, unsettling, or even intolerable for reasons that include being able to hear their own heartbeats and other bodily functions, given the lack of “interfering” sound. Similarly, ambient “silence” (in this case, low or intermittently low background sound levels) in an office makes surrounding conversations and acoustical disturbances easier to hear.

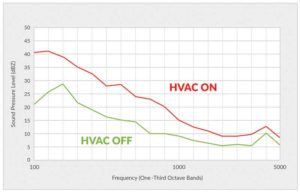

The perception of sounds is affected by other sounds present within the space, and particularly by its ambient acoustic conditions (i.e. background sound). The physics behind this effect was documented as early as the 1950s and referred to as the Masking Effect. To be clear, it does not explain human acceptance or assessment of sounds, only the ability to hear, identify, and differentiate between them. It is an effect routinely experienced in everyday life due to things such as blowing wind, running water, a murmuring crowd, HVAC), but rarely thought about in the context of the built environment. That said, the only time such ambient sound typically falls below the threshold of hearing is when special effort is made to reduce it, as in an anechoic chamber or recording studio. Since it is present in just about every environment inhabited, in addition to making people more vulnerable to acoustical disturbances, its absence can also feel “unnatural.”