Designing workplaces to minimize noise and sound impact

Acoustics and ‘good design’

Whereas the metrics on which people principally rely (i.e. sound level, reverberation time, absorption, sound insulation, vibration isolation) to quantify the acoustic properties of materials, assemblies and spaces cannot be used to indicate or assess a person’s acoustical experience, the large POE datasets, such as those compiled by the CBE, do empower building professionals to make practical, data-driven decisions intended to achieve occupant-centric goals (e.g. focus, comfort, privacy).

Parkinson et al. points out that bridging the gap between this data and actionable insights to improve workspaces “may require a shift in focus from the determinants of overall satisfaction to common sources of occupant dissatisfaction.” It also involves centering design on the main way employees use these facilities. According to Gensler’s U.S. Workplace Survey 2022, most employees primarily use the office as a dedicated space for focused work, and they spend most of their time working independently. Moreover, 69 per cent of these tasks demand a significant level of concentration. The firm concludes that supporting this type of work provides “a crucial foundation of the workplace experience,” but, at the same time, their data indicates workplace effectiveness in this regard has declined to the lowest levels since 2008.9

While design trends have increasingly favoured collaboration over the last decade, given that “poor acoustics” is the number one cause of dissatisfaction and focus work is the primary objective of those using offices, it is clearly time to prioritize occupants’ need for quiet and privacy. Fortunately, spaces designed to facilitate concentration have also proven to be more conducive to collaboration than those primarily designed for collaboration.

Of course, offering adjunct spaces where employees can join their colleagues for face-to-face time is also important. Considering 72 per cent of adults report feeling lonely—and hyposensitive neurodiverse individuals require more, rather than less, sensory stimulation to focus and feel safe in social engagement—communal areas that help build relationships and offer more ‘energetic’ acoustics also support mental health and well-being.10

Organizations can also offer additional aural experiences such as relaxation rooms that employ natural sounds to stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system (i.e. a “rest and digest” state). Providing a variety of spaces with different auditory features from which to select has the added benefit of increasing occupants’ feelings of control over their work environment.10

That said, self-awareness is likely insufficient to achieve occupant-centric goals because there are aspects of the environment that occupants may not consciously recognize or fully appreciate as being either beneficial or detrimental to health and well-being—and, at the same time, are not adequately accounted for in current noise-rating systems or even in recently developed building standards geared towards well-being.

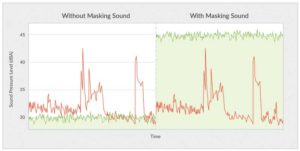

Indeed, the general public’s understanding of acoustics continues to primarily be informed by noise exposure theory and its focus on level or, more colloquially, “loudness.”11 Hence, the answer to the question “What constitutes ‘good acoustics’ within the workplace?” is often simply “an environment with little to no noise.” Given this viewpoint, the notion of intentionally raising the ambient acoustic environment to achieve a quieter one—or, rather, one occupants will perceive as quiet—may seem counterintuitive, but, contrary to popular understanding, the perceptions of sound have less to do with the lowest level of sound humans can hear, and more to do with the ability to identify and discern sounds within an acoustic environment.