Designing for timber-framed buildings

Photos © Matthew Reid

While in some respects it is reasonable to assume a building has stood the ‘test of time,’ one cannot assume all inadequacies will have revealed themselves over the years. While the building may have performed satisfactorily in its previous life, even if the change in occupancy brings a theoretical loading reduction, there is no guarantee the building will be suitable for its repurposed life.

Repurposing can involve various changes, but with respect to the timber structure, one can generally break down the work into two broad categories: minor changes and repairs, and major renovation and remediation. Minor changes may involve alterations for new mechanical equipment and services as well as a change in occupancy, but not significant changes in the loading of the building. In general, this would require the engineer to get a feel for the structure’s capacity. Timber varies in grade and species, but some basic reasonable assumptions, based on the building’s approximate age, can expedite the process and preclude a full and costly grading assessment of the timbers.

For light framing (usually full-dimension, rough sawn lumber), one can typically assume Spruce-Pine-fir #2/Northern Select Structural when assessing minor changes. (These two species gradings are conveniently close in strength and past gradings have rarely been found to deviate.) (The noted assumptions for species and grade are particular for Southern Ontario, but similar trends can no doubt be determined for other regions based on common historic building practice).

For heavy timber construction, historic buildings are generally found to fall into two possible scenarios as far as grading is concerned. For structures in the range of less than 80 to 100 years old, one generally finds timbers to be Douglas fir, grading to No. 1 or better. Older timber structures (and particularly those built before the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway [CPR]) tend to be of Northern species—Select Structural being common. However, these assumptions are just a starting point, and though such findings are very common, one can just as easily encounter timber framing that includes, for instance, maple and elm in the mix.

For heavy timber construction, historic buildings are generally found to fall into two possible scenarios as far as grading is concerned. For structures in the range of less than 80 to 100 years old, one generally finds timbers to be Douglas fir, grading to No. 1 or better. Older timber structures (and particularly those built before the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway [CPR]) tend to be of Northern species—Select Structural being common. However, these assumptions are just a starting point, and though such findings are very common, one can just as easily encounter timber framing that includes, for instance, maple and elm in the mix.

Major renovations, residential conversions in particular, frequently include the addition of a concrete topping to deal with sound and other performance issues. In this case, if assumptions do not provide an obvious and favourable result—such as a load capacity well in excess of what is required by current codes—a full grading assessment of the timbers, complete with sampling for determination of species, may well be required.

In-situ grading of timbers is a specialized skill. Licensed timber-graders employed at a sawmill will not grade timber beams and columns in an existing building. Since all four sides of beams are rarely exposed to view, a complete grading cannot be performed. This is where engineering experience and judgement combine with grading skills to assess the in-situ condition. (The Ontario Forest Industries Association (OFIA) offers timber-grading courses).

In addition to generally accepted engineering principles and conventions, building codes provide additional guidance for assessing existing structures. NBC includes Commentary L, “Application of NBC Part 4 of Division B for the Structural Evaluation and Upgrading of Existing Buildings.” This commentary principally addresses criteria for the ultimate limit state (ULS) affecting life safety. Commentary L includes a method of evaluation based on past performance (for all loadings except for seismic) and provisions for reduced load factors based on risk category and a calculated reliability level. Reduced load factors are used as a measure of the performance of the existing structure against new loading requirements. If upgrades are necessary, the intention is one would then revert to the full requirements of Part 4, Structural Design, for any upgrade. When an upgrade is required, there is no significant potential for savings to use reduced factors as most of the cost will be labour, not materials.

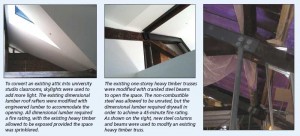

An interesting creative aspect to structural engineering is upgrading a building’s structural capacity. There are three basic options: simply replace the member, reinforce the member, or unload the member. Replacing the member seems simple on the drawings, but the design team needs to consider the feasibility of construction. Requirements for shoring and the accessibility of cranes or lifts need to be carefully considered.

Likewise, reinforcing a member can be quite simple or complicated, depending on the context. Considerations include how the load is transferred into the new reinforcing, how the load then gets transferred back out of the reinforcing and into the building structure, and potentially jacking of the existing structure or pre-loading of the reinforcing to balance the load distribution.

Unloading a member is certainly easier said than done. Shortening the span of a beam (adding a column for instance) will usually have significant implications—particularly from an architectural standpoint.

The bottom line

The costs on any building project are always closely scrutinized. Of course, owners and developers like fixed fees, especially when it comes to paying for consultants. For most consultants—architectural, mechanical, electrical, civil, landscape—involved with repurposing an historic building, a fixed fee is relatively easy to determine. For instance, renovations usually involve completely new mechanical and electrical systems, so from that perspective it is comparable to new construction.

A fixed fee for structural engineering services related to the assessment and renovation of an historic building is tremendously difficult to determine because a complete scope is nearly impossible to determine before performing the work—old buildings tend to be full of surprises. Who could predict a four-storey, four-wythe brick bearing wall would just be sitting on a slab-on-grade and have no foundation wall or footing?

In the authors’ experience, fees from past projects have ranged from as low as a couple of thousand dollars up to many tens of thousands—and the fees do not necessarily directly relate to the building size. From a structural engineer’s perspective, the best practice is to proceed on an hourly basis until the faults of the building are known, and then attempt to carefully define the scope and corresponding fees.

Adaptive reuse of historical buildings is not the cheapest form of construction and better returns on investment (ROIs) can likely be found elsewhere. However, cheap construction costs are not the driving force behind adaptive reuse. From heritage conservation of prime locations to recycling buildings and creating unique and uniquely marketable spaces, such endeavours can be profitable. Historic timber buildings are worth preserving. They just sometimes require a little work, particularly when sound and fire and the effects on structure are concerned.

Matthew Reid, MASc., P.Eng., is an associate with Blackwell Bowick Partnership Limited Structural Engineers in the Toronto head office. He has worked at Blackwell Bowick for five years, completing mainly renovations and additions to institutional, commercial, and residential projects. Reid sits on the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) Technical Committee A307 on Solid and Engineered Wood Products, and completed his Master’s thesis in 2004 on Bolted Connections in Glued Laminated Timber. He can be contacted via e-mail at mreid@blackwellbowick.com.

Cory Zurell, PhD, P.Eng., is a senior associate with Blackwell Bowick Partnership Limited Structural Engineers and directs the firm’s Waterloo, Ont., office. He is also an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Waterloo School of Architecture and sits on the APA–Engineered Wood Association’s Standards Committee on Cross-laminated Timber Panels. Zurell has been involved in structural consulting and education for 14 years and has a particular affinity for timber structures. He can be reached at czurell@blackwellbowick.com.