Demystifying self-consolidating concrete

Plastic performance of SCC

Images © Michael Stanzel

The workability of SCC describes the mixture’s ability to be mixed, transported, placed, consolidated, and finished. It is often described in terms of a mixture’s:

- filling ability, or the ease with which SCC can flow into and completely fill all spaces within the form;

- passing ability, or the ease with which SCC can pass around various obstacles and through narrow spacing without resulting in blockage; and

- stability, or the ability of the mixture to maintain homogeneity during both its flow (dynamic) and while at rest (static).

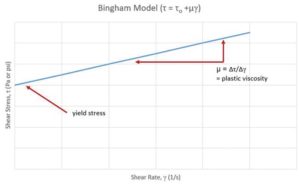

The robustness of a SCC mixture can be regarded as its ability to maintain its rheological properties though the various production and construction stages. SCC rheology is often quantified through:

- static yield stress, or the minimum shear stress to initiate flow from rest;

- dynamic yield stress, or the minimum shear stress to maintain flow once in motion;

- plastic viscosity, or the change in shear stress as the shear rate changes (important for stickiness and cohesion); and

- thixotropy, or the reversible, time-dependent reduction in viscosity in a material subject to shear forces influencing its ability to gel while at rest (Figure 3).

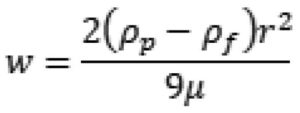

Consideration of Stoke’s Law provides valuable insight into the segregation potential of a mixture:

Where w is the settling velocity, rp and rf are the particle and fluid densities, r is the radius of the particle, and μ is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid.

Since SCC is a suspension of particles within a fluid, the frictional forces from particle interlock, due to shape and texture, also play a role. As is evidenced by the structure of the equation, having a lesser density difference between the particles and fluid, a smaller particle size, and a higher viscosity reduces the settling velocity and chance of segregation.

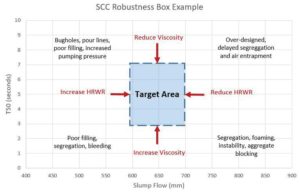

Although a number of test methods are suitable for prequalification and acceptance of SCC, the most practical and easiest to use and interpret onsite is the Robustness Box, a combination of both the slump flow (and visual stability index) and T-50 cm time test information in an easy-to-interpret chart. Essentially, SCC can be quantified by:

- amount of flow, indicative of the yield stress; and

- rate of flow, indicative of the viscosity (Figure 4).

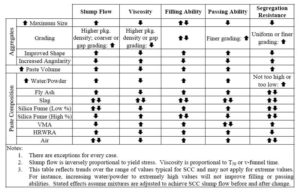

Depending on placement considerations, materials, ambient conditions, and the target slump flow itself, there exists a certain window for both the slump flow and T50 that is advisable to stay within to ensure good flow and minimize segregation. The key strategy when using the Robustness Box is understanding what changes in the mixture proportions will cause the performance to move outside the ideal parameters. Assuming a properly designed combined material gradation, the two main levers available to adjust the mix are:

- the high-range water reducer dosage that has a significant impact on the slump flow and a minor impact on the time; and

- ‘thickness’ of the mix that has a significant impact on the time and minor impact on the slump flow.

Image courtesy “ICAR Mixture Proportioning Procedure for SCC” by E.P. Koehler, and D.W. Fowler (2007), International Center for Aggregates Research, Austin, Tex.

Increasing the thickness can be achieved by reducing the water content and coarser aggregate, increasing the cementitious content and fine aggregate proportions, or through use of a viscosity-modifying admixture. This admixture increases viscosity at rest but allows a lower viscosity when flowing (Figure 5).

The rheology can thus be optimized for a particular project with the appropriate:

- low dynamic yield stress and adequate plastic viscosity and thixotropy in order to ensure self-consolidation;

- increased static yield stress due to thixotropy to ensure reduced formwork pressures and sufficient viscosity for segregation resistance; and

- appropriate plastic viscosity and stability for pumping applications.