Danger Overhead: Ensuring future access for the façade

Making choices

From a designer’s perspective, façade access can be roughly classified as proactive and reactive. The latter includes all portable equipment, such as:

- aerial platforms;

- truck cranes;

- parapet hooks;

- counterweighted outriggers;

- ladders;

- boatswain’s chairs;

- supported scaffolds; and

- powered platforms.

It is assumed they can be rented out and brought to the site by a service contractor.

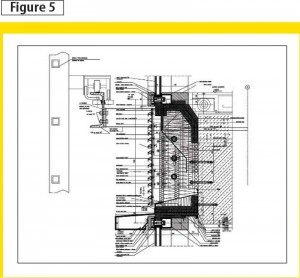

Proactive measures include all permanent anchorage and equipment and can be further divided into standard and dedicated systems. Myriad manufacturers provide standard systems at differing levels of utility, ranging from simple loop davits and guards to house cranes. The dedicated systems are custom-engineered to respond to a challenge created by a specific building—gantries, for instance, are almost always created for safe access to a specific bridge or a skylight (Figure 5). Vertical gantries are a very effective means of wall access, coupled with recently-in-fashion architectural accent bands that can be engineered to serve as horizontal rails.

The need for access anchors and tie-offs typically arises unless all façades are accessible by portable off-the-street equipment and the roofs are free from any fall hazard (e.g. fully surrounded by tall parapet walls). The choice of equipment and anchorage is up to the owner, as it is mainly a financial dilemma of weighing the initial cost versus the long-term one over the building lifecycle. Smaller buildings inaccessible from any driveway (as is often the case with courtyards and monumental lobbies) may also require dedicated provisions for access.

There are boom lifts and truck cranes that can reach above 39.6 m (130 ft) at a high rental cost. The interior façades can be frequently accessed by aerial platforms, providing the doors, elevators, and corridors on the way have sufficient size and capacity to allow for transportation. For situations where permanent equipment is the only means of access to the façade (e.g. buildings taller than 91 m [300 ft]), an architect should provide a design solution co-ordinated with structural, electrical, and façade engineering.

These dedicated, permanent solutions are characterized by a higher initial cost and hard-to-calculate return on investment (ROI). Every project is different. Most glass manufacturers require frequent washing of window glass—about every three months—to keep the glazing free from corrosive residues. As-needed repairs may turn out to be required more often than initially expected. The duration of work may extend beyond initial expectations. This author has heard the George Washington Bridge connecting New York and New Jersey needs to be repainted only every two years—but since the repainting process takes two years, the suspended gantry underneath the bridge is operated on an ongoing basis.

Important long-term consideration is the downtime of crews performing the work. It is not uncommon for a building to have only two dedicated davit arms that must be relocated by hand, requiring several people to lift. Every time a scaffold finishes a drop, the crew needs to move the arms and reels of cable from one socket to another, as opposed to having two spare davit arms simultaneously installed on the next drop. Quick and constant façade access would reduce both schedule and budget uncertainty due to the weather.

In other instances, the nearest electrical outlet may be too far away for the powered scaffold, which typically needs a three-phase 230-V supply. A dedicated, splash-proof outlet and water bib should be available at strategic locations, serving roofs and façades.

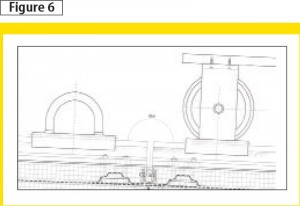

Another important consideration is ease of use. A worker who needs to detach and tie his or her lanyard repeatedly is not only left without protection while doing so, but is also less productive than a worker able to rely on a building’s monorail system, moving a trolley along the rail (Figure 6).

Among the dedicated solutions, the most economical solution is a single BMU. These units require a contiguous, dedicated perimeter of roof or parapet wall close enough to at least one spot near the podium in such a way that it is possible to park the platform with some access to and from a public road (so an average size truck may be loaded and unloaded in front).

Building shapes, sizes, and locations

The obstructions are typically of architectural character. In the past, many designers of high-rises loved fragmented roofs—a low-slope area here, a steep slope there, and a terrace over the way. Today, the current fashion can eliminate roofs, as a curtain wall slopes back into a glazed assembly instead, creating a similar challenge.

The courtyards among the podiums can also be glazed, creating impenetrable and inaccessible zones usually marked by wildlife nests and thick deposits of dirt and debris due to the difficult access for maintenance. The ultimate result is an expensive BMU may serve only a fragment of a building, and an owner (or insurance company) would still need to spend $5000 daily for rental of a hydraulic crane.

Another caveat is the shape of the building façade plan. Deep pockets and narrow recessions in a façade can not only make swinging platforms access impractical or impossible, but also render them out of human reach. This situation may result in construction defects and deferred maintenance.

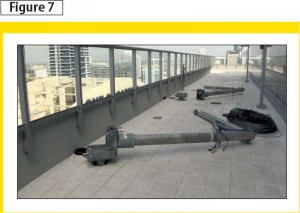

Additionally, a frequent picture is a service contractor installing a portable rig in front of a perfectly good in-house access system. Possible reasons include a house rig may be too challenging to work with—it may require, for example, temporary dismantling of façade finishes and relocation by a crew of several labourers (Figure 7). A BMU often requires a skilled and certified operator who would either need to be permanently employed or temporarily hired by the owner or a contractor. A rig like this requires annual inspection and maintenance, which might have been postponed by the owner.

Hazards may be created by the very fall-arrest systems intended to prevent them. For example, there are davits located at the edge of a roof that require a worker to approach them to install a façade fall arrest system, but do not allow for an earlier personal fall-arrest tie-in. They should be protected by a secondary means of fall arrest, which would allow for their approach.

Falls are not only dangerous on high-rises. A few years ago, this author was inspecting more than 40 roofs of a community of low-rise, multi-family, residential buildings in Miami. A 7.6-m (25-ft), extended, portable ladder was the only means of access, there was no lifeline or davits—nothing to protect a worker from a free fall. While walking on one of the roofs, a flat portion of its deck began to collapse. On a close-up investigation, the deck turned out to be rotten.

Low-rise buildings often avoid the scrutiny reserved for taller buildings and are typically void of any safeguards expected in high-rise construction. This often makes them the most dangerous. After all, it does not make much of a difference to fall 7 or 70 m—the result is usually the same.

Conclusion

Façade access, along with the requisite safety systems, is among the items most often overlooked by designers. However, the need for access becomes acutely obvious in the early construction phase; the necessary addition of window-washing equipment comes as a late and unwelcome surprise and plays havoc with design, budget, and construction schedule. Understanding the various BMU and fall-arrest systems is critical for both architects and specifiers.

Karol Kazmierczak, CSI, CDT, AIA, ASHRAE, NCARB, LEED AP, is the senior building science architect and president at Building Enclosure Consulting LLC. The current leader of the Building Enclosure Council (BEC) Miami, he has 16 years of experience in envelope design, engineering, consulting, and inspection. Kazmierczak can be contacted via e-mail at info@b-e-c.info.

Jerzy Tuscher, M.Sc., is the president of Biuro Techniczne Tuscher. He has 34 years of architectural façade engineering experience. Tuscher can be reached at george@b-e-c.us.