Curtain walls and energy codes

Images courtesy Vladimir Mikler

Thermal performance of curtain walls must also include improved thermal break designs of the framing and support systems. Additionally, the thermal break design of the framing systems must improve along with the number of panes and/or suspended films being used in the sealed glass windows. Using a poor thermal break framing system can compromise even the best-performing window.

Solar performance

Even in Canada’s climate, solar gain through windows incurs the need for a great deal of energy-demanding cooling systems. The current architectural esthetic and building marketing trend is for as much window area as possible—sacrificing energy efficiency in the name of having nice views.

Curtain wall systems with essentially 100 per cent floor-to-ceiling window area are still being proposed, based on the economic first cost aspect of that type of building cladding system, with the availability of low-energy HVAC systems to compensate for the low thermal performance of an all-glass exterior wall. Triple-glazed, low-e-coated, argon-filled sealed glass elements can compensate somewhat for the extensive window area, but as the codes require better envelope performance, how far will all-glass curtain wall systems have to go?

There are some suspended film sealed window units that, with krypton gas fill, can provide:

- centre-of-glass U-values as low as 0.07;

- solar heat gain coefficients (SHGCs) of 0.23; and

- visible light transmittance (VLT) of 41 per cent.

While this may be considered exotic by North American sensibilities, it is interesting to note Europe has been using triple- and quadruple-glazed (i.e. suspended film) window systems for the last 30 years, as their energy codes have been driving up the window performance requirements. Further, Chinese production of these window systems is being refined to a very high quality level, which should make economic availability widely available.

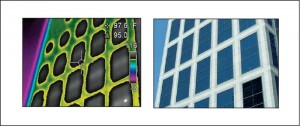

Photos © Geoff McDonell

The key to successful application of extensive curtain wall systems to meet better solar gain performance (and, therefore, lower energy use goals) is to:

- reduce the WWR;

- use heavier tints and more layers of glass and/or suspended films if the code-minimum ratio is exceeded; or

- specify exterior shading devices to allow less tints and higher VLT in either case.

There is always a compromise—glazing optimized for best heating performance (i.e. lowest heat loss), is not the best for cooling reduction performance, and vice versa. The envelope and glass design must be climate-adapted for the project’s specific location and orientation.

Careful selection of window tints will have to be made. For example, use of ‘heat-absorbing glass’ can be a boon in a sunny but cold climate zone, but it introduces the risk of creating higher air-conditioning loads in the summer. This is because the inner surface of the glass can reach very high surface temperatures, creating large radiant heating panels.

Ceramic fritting is another alternative for solar gain control, and can be designed into various patterns and densities for controlling glare and providing better quality daylighting. The use of light-coloured fritting on the inner surface of the outer glass panel can be an effective solar heat gain control element that helps reduce the need for tints; it also lowers the glass temperature on sunny days compared to conventional heat-absorbing heavily tinted glass.

Fritting has to be carefully designed. While the ceramic pattern reduces the direct solar heat gains entering the occupied space, the fritting absorbs heat and causes the glazing to warm up. This potentially creates some radiant heating from the warmed inner glass surface.

Daylighting

Hand in hand with improved solar gain reductions required for high-performance curtain walls comes the need to maintain a high degree of daylighting to offset the electrical loads from powered lighting systems inside the building. Most architects believe having more windows is better for ‘natural lighting,’ but this author sees a lot of floor-to-ceiling glazed buildings on sunny days with the blinds closed. In some cases, the occupants have applied their own solar control devices in the form of foil and drapes.

There is a big difference between daylighting with natural light and having direct sunlight streaming in through a window. Good daylighting can result in esthetically pleasing, appropriately lit spaces while saving energy. A successfully daylit building is the result of a combination of art and science, of architecture and engineering. It is the culmination of an integrated design process, rather than simply a technology installed once the building is complete.

The design key is to harvest good quantities of diffuse, non-glaring natural light through well-specified spectrally selective windows, appropriately sized and located (i.e. ‘tuned’ to the building façade). More window area does not result in much more effective daylighting, and the corollary reduction in electric lighting energy.

The example pictured at the top of this page illustrates a common perception. The windows were based on a four-element window system that had a VLT of only nine per cent. There was a decision made to eliminate any interior shading devices (i.e. blinds and drapes), as the design team feared a lack of daylighting through such a low-VLT window.

A couple summers after the building was leased out, the occupants were complaining about too much daylighting, and it was causing a glare on their computer screens. The entire building was retrofitted with interior sheer drapes to reduce the glare and allow more diffuse natural light into the perimeter offices. The moral is the design esthetic of using a lot of glass for transparency and natural light must be understood and properly applied. (References and links to design resources can be found at www.daylighting.org/design.php. The Canadian Commercial Building Daylighting Guide is available at www.enermodal.com/pdf/DaylightingGuideforCanadianBuildingsFinal6.pdf).

While the evolving building energy codes appear to be pushing building designers to use less windows and glass, this does not mean opportunities for effective natural lighting will have to be compromised. If the clean smooth exterior façade design precludes use of exterior shading devices, then tinted and spectrally selective glazing systems will be required, as well as reduced WWRs. Where exterior shading can be used, then less tint and more window area could be specified, albeit with higher thermal performance criteria to meet the energy performance goals.

Numerous technical studies around the world, including extensive in-house modelling at Cobalt LLP, have shown there is a ‘sweet spot’ for optimal window-to-wall ratios of around 30 to 40 per cent for northern, heating-dominated climates, which results in the best daylighting and envelope thermal performance.

Conclusion

Low-e coatings, gas fills, warm-edge spacers, and thermally broken frames are becoming available at reasonable costs. Driven by the increasing demands of stricter energy code compliance requirements, these available technologies will need to be combined with multiple-layer glazings, dynamically controllable shading, highly-insulated frames, and other options.

An astute building design team should be able to combine the savings from mechanical and electrical systems to pay for the apparent ‘premium’ of very high-performance curtain wall systems, satisfying tight budget constraints. For every dollar spent on the building envelope, a dollar can be saved from the HVAC and lighting systems, and result in significantly lower energy and operating costs for the building’s life. An economically designed structure with lower operating and maintenance costs, and increased indoor comfort ought to be an easy sell for building owners and

leasing agents.

New building designs using curtain wall cladding must adjust to the future energy code developments by fundamental design shifts:

- reducing the amount of vision glass and also increasing the areas of the better-insulated spandrel panels;

- improving sealed glazing unit thermal performance through additional glazing layers or suspended films to create more air spaces;

- detailing of the enhanced thermally broken framing systems; and

- integrating new technologies such as thin-film photovoltaic (PV) skins, articulated exterior shading, and electrically variable glass tinting systems.

Given the gestation period of building designs—from initial concept, through re-zonings and development permit processes—it can take anywhere from two to three years before the building permit stage is reached, so project teams must recognize the evolution of code-driven energy performance requirements, and future-proof their designs to ensure project budgets and cladding systems reflect the built environment’s new realities.

Geoff McDonell, P.Eng., LEED AP, is an associate partner at Cobalt Engineering LLP in Vancouver. He has more than 30 years of experience in mechanical engineering, and is a registered mechanical engineer in British Columbia and Alberta. McDonell specializes in low-energy mechanical systems, including radiant cooling applications, Passivhaus style designs, and assisting architects with building envelope performance evaluations. A LEED AP since 2001, he was a speaker at the first Greenbuild conference. He can be contacted via e-mail at gmcdonell@cobaltengineering.com.