Core Sunlighting Technology: Offering a new approach to green building

Cost and energy analysis

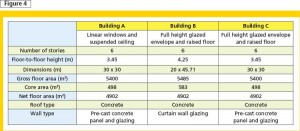

For the purpose of this cost and energy analysis, the authors present data based on the climatic conditions for Chicago, since it is representative of a typical city that experiences fairly hot summers and fairly cold winters. (They have also carried out the same analysis for Vancouver, which has a more temperate climate. While the numbers are somewhat different, the overall conclusion remains the same.)

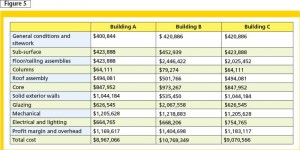

To determine the capital cost for each building, the authors used a common construction costing analysis that is standard industry practice at the feasibility and conceptual design phases. This approach employs an assembly cost estimation to determine the cost per square metre for the construction assemblies, and further unit cost input from a large local construction firm. They used a building information modelling (BIM) program to model the buildings and generate the main assembly schedules and areas, and the unit costs were applied to obtain assembly costs. (Visit www.usa.autodesk.com/revit-architecture). Then they applied the city cost indexes to adjust these costs for Chicago (about five per cent higher than Vancouver). (All monetary figures in this article have been converted into Canadian currency).

Since core sunlighting systems are in an early stage of development, comprehensive cost data is not available at this time. For the purpose of this analysis, the authors estimated Building C would incorporate 10 sunlight concentrators, each 3 m (9.9 ft) wide, on every floor on the south façade of the building, for a total of 60 concentrators, each having a total installed cost of $1500. This increased the cost of the lighting for Building C by $90,000 above Building A, but there were no other changes to the cost as a result of the core sunlighting system. (The cost per concentrator used in this analysis represents a reasonable target for a cost-effective core sunlighting system manufactured in modest industrial volumes of 1000 monthly) The anticipated capital costs for each building are summarized in Figure 5.

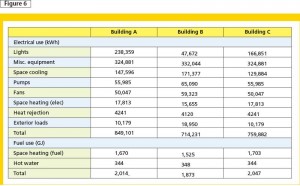

Next, the authors considered the energy use in each building, and again implemented the available practice tools commonly used at the feasibility/conceptual design phase. Energy analysis software (Visit www.greenbuildingstudio.com for more information). was used with the building models to calculate the energy requirements for each building using the regional climatic database for Chicago and a specified occupancy profile (i.e. process load) common to all three buildings. The program calculates the annual energy requirements for the building, in terms of electrical (i.e. lights, HVAC electrical equipment, exterior loads, and miscellaneous equipment), and fuel use for space heating and hot water.

A core sunlighting system is not yet an integrated option in these software packages. To account for the energy savings in Building C as a result of the core sunlighting system, the authors reduced the electrical energy required for lighting by 30 per cent of the value that was calculated for Building A. This value was determined using the approximate direct sunshine probability of 50 per cent (taken from historical weather data for Chicago), (For annual sunshine hours in Chicago, visit www.rssweather.com/climate/Illinois/Chicago). and the approximate fraction of Building A that was illuminated solely by electric lights (60 per cent).

The electrical energy required for space cooling was reduced by 12 per cent to account for the reduction in heating load associated with turning off the electric lights half the time during the summer. Similarly, the fuel required for space heating was increased by two per cent, to account for the decrease in heating load during the winter. The energy intensity values calculated for the three buildings are shown in Figure 6. (These values are reasonable compared to the average value for office buildings in Canada, which is about 1.2 GJ/m2/year.)

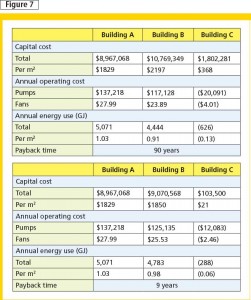

The authors then calculated the simple economic payback time, based on the capital cost and the operating cost, for Buildings B and C, compared to the base design of Building A. (The operating cost was calculated using the annual energy use above, using an electrical energy cost of $0.139/kWh and a fuel cost of $9.53/GJ.) (Recent electricity and fuel costs for Chicago can be found at www.bls.gov/ro5/aepchi.htm). These comparisons, along with the annual energy savings, are provided in Figure 7.

Figure 7 illustrates the conventional daylighting design results in about twice the energy savings of that achieved by the core sunlighting system, but it costs 20 per cent more than the basic design, whereas the core sunlighting system costs only one per cent more. This suggests as new core sunlighting systems become available, they will be the most cost-effective method for daylighting buildings.

Implications for the green building industry

Daylighting and occupant comfort present conflicting challenges in green buildings—a high fenestration ratio is desirable for bringing in natural light, but large expanses of glazing result in undesirable solar gain at some times of the year and loss of heat at other times. Furthermore, the incremental cost that is associated with higher floor-to-floor spacing, increased glazing, and increased perimeter area is often not justified by the resulting energy savings, and the simple economic payback time tends to be unreasonably long.

With practical core sunlighting systems coming onto the market, buildings can be daylit at a reasonable cost. The comparison of the three representative buildings shows though the conventional daylighting design can save twice as much energy as the one incorporating core sunlighting, it costs about 20 times as much.

Additionally, the core sunlighting approach overcomes many of the inherent conflicts with thermal comfort and glare that conventionally daylit buildings face, by enabling more modest fenestration ratios and directing sunlight downward from the ceiling in a glare-free manner. Consequently, with the advent of these new systems, an optimal method for daylighting buildings under most circumstances will involve a combination of core sunlighting in deep spaces and conventional daylighting near the perimeter.

Lorne Whitehead, PhD, P.Eng., is a professor at the University of British Columbia (UBC). He is the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada (NSERC)/3M Company Industrial Research Chairholder in Applied Physics and the chair of the Board of Directors of SunCentral. Whitehead is a member of the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America (IESNA) and has 27 years of experience in illuminating engineering. He can be contacted via e-mail at lorne.whitehead@ubc.ca.

Donald Yen, MAIBC, MRAIC, is a registered architect in British Columbia and Washington, and has 24 years of experience in the profession of architecture and sustainable design. He instructs in the areas of sustainable urban development and architectural and a structural computer-aided design and drafting (CADD) and graphics at the B.C. Institute of Technology (BCIT). Yen can be reached at donald_yen@bcit.ca.

Robert Salikan, MAIBC, AAA, MRAIC, is a principal at Salikan Architecture, a firm established in 1988, with projects in British Columbia, Alberta, the United States, and Japan. He is a registered architect in British Columbia and Alberta, and has 30 years of experience in architecture. Salikan can be contacted at robert@salikanarchitecture.ca.