Core Sunlighting Technology: Offering a new approach to green building

By Lorne Whitehead, PhD, P.Eng., Donald Yen, MAIBC, MRAIC, and Robert Salikan, MAIBC, AAA, MRAIC

Recent technological advances have made it practical to deliver concentrated sunlight deep inside buildings. This new approach to energy-efficient lighting means almost all areas of a building can be illuminated whenever the sun shines without requiring any increase in floor-to-floor height or large expanses of glazing. As a result, core sunlighting has the potential to significantly influence how the building industry optimizes green building designs.

This article compares the performance of a core sunlighting system, in terms of energy savings and cost, to that of an alternate design using the standard daylighting strategies that have become common in green buildings. This comparison shows a building employing a core sunlighting system provides significant electrical energy savings at significantly lower capital cost per kWh/year saved.

It has become a building industry-wide challenge to illuminate interior spaces while consuming as little electrical energy as possible. Daylight, when used well, creates spaces most people find pleasant and healthy, and good daylighting delivers on the triple bottom line since saving energy is also economically and environmentally sound. There is no question daylighting is a desirable way to illuminate a building. The challenge is how best to do it.

The value of core sunlighting

Daylighting enters a building in numerous ways, including windows, light shelves, and skylights—these approaches offer good solutions for perimeter spaces. However, when these areas are brightly lit by natural light, increased electric lighting is often needed in the core to provide balanced illumination, so daylight at the perimeter can actually lead to greater use of electrical energy.

To mitigate this problem, sustainable buildings are often designed with narrow floor plates, high ceilings, and high fenestration ratios, as well as interior atria and courtyards, effectively eliminating the core. Such ‘macro’ building design solutions enable daylight to penetrate throughout the building, but they have several disadvantages.

For instance, they cannot address the need to reduce the energy consumption of existing buildings, many of which have large floor plates. They also may not work well with the specific site conditions, or with the building’s functional program requirements—a large, continuous floor plate may be necessary, for example. Moreover, there are trade-offs associated with maximizing daylight using large areas of glazing. More stringent thermal and glare controls are required, and these tend to increase complexity and reduce overall illumination quality.

In addition to such considerations, the most important concern with this approach boils down to cost—enlarging the perimeter is a more expensive way of illuminating the building since the construction cost per unit area of floor space is significantly increased. It could perhaps be argued that, in the absence of a better solution, this increased cost is warranted to save electrical lighting energy and provide the other benefits of daylight.

However, now that cost-effective commercial lighting systems that pipe sunlight deep into the core are emerging in the marketplace, a narrow, high-fenestration-ratio design is no longer the only way to fully daylight the space. The idea of core sunlighting is not a new one, (See Sustainable Building Technical Manual: Green Building Design, Construction, and Operations, a publication produced in 1996 by the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) and sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [EPA]). but new optical materials and designs make this concept practical and affordable. (Visit www.phas.ubc.ca/ssp/CoreSun_index.html for more information). Recent demonstration systems have shown concentrated sunlight delivered into the building core significantly reduces the energy used for electric lighting and illuminates the space with a lighting quality most people prefer.

Core sunlighting involves harvesting sunlight at the perimeter of the building, moderately concentrating it, transporting it into the building, and controllably releasing it deep inside as illumination. Significant electrical energy savings can be achieved by incorporating automated lighting controls that turn off the supplemental electric lights whenever adequate sunshine is available.

A properly designed core sunlighting system can deliver illumination that has the advantages of high-quality electric lighting while also providing the benefits of daylight, including excellent colour-rendering properties and a greater sense of connection to the outdoor environment. Since the windows are no longer required to provide all the daylighting in the space, they can be sized appropriately to focus on the desired views while optimizing building envelope environmental control.

Image courtesy Willie Dean, Glumac

The challenge of cost

The most challenging issue that has arisen in the area of core sunlighting is one that is fundamentally important (and often overlooked) with most solar technologies—that of up-front capital cost. To be successful, core sunlighting solutions must use optimized, cost-effective materials and volume manufacturing techniques so as not to significantly increase the price of any of the other building components.

The capital investment in any building system is dominated by the structure itself, which means a real expense must be attributed to each cubic metre of space within a building and each square metre of its surface area. This leads to the conclusion any daylighting approach intended to save energy (and therefore, money) has an effective additional capital cost determined by the volume and surface area of the building it occupies.

From this perspective, conventional daylighting approaches requiring increased floor-to-floor spacing may not provide a commensurate net economic benefit in terms of the resultant energy savings. In contrast, concentrated sunlight piped inside the already existing plenum requires much less space and, therefore, does not share the same capital cost burden. It is important to emphasize this conclusion only applies to passive daylighting for core spaces. Daylighting in perimeter spaces using windows and skylights is a practical and cost-effective approach, particularly if it is employed in combination with core sunlighting systems to form a complete natural lighting system for the building.

Images courtesy SunCentral

A practical approach

Cost-effective core sunlighting technologies are emerging, and one system in particular has shown the potential for cost effectiveness. This approach, invented at the University of British Columbia (UBC), uses a sunlight concentrator to collect and concentrate the sunlight, and a hybrid light guide for distributing it inside the building.

The concentrators are incorporated into the façade above the windows and housed in a protective enclosure. To capture the sunlight, small mirrors move in unison to track the sun’s motion throughout the day. Once the sunlight has been redirected by the automated mirror array, it is concentrated by about a factor of 10—sufficiently concentrated to substantially reduce the space required within the building for distribution, but not so concentrated as to pose any possibility of a fire hazard.

The concentrated sunbeam is then directed through a small window in the exterior wall and into the specially designed hybrid light guides, which are integrated with dimmable electric lamps and sensors that monitor the illumination level so the sunlight can be supplemented when required (Figure 1).

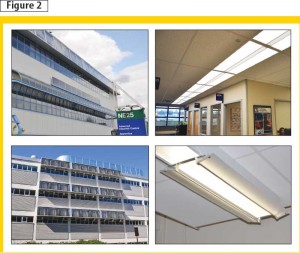

Two recent demonstration systems, funded by federal and provincial government grants and a consortium of industry partners, have been installed in buildings in the Vancouver area to show the technology can be seamlessly integrated with standard construction techniques (Figure 2). Preliminary verification indicates the performance matches the predictions that were generated using historical weather data for the region. Long-term verification of the energy savings and occupant experience surveys are ongoing.

The system has been highlighted to show the concept of core sunlighting is no longer just a theoretical possibility, but rather it is now a practical and affordable daylighting alternative. Other technologies currently under development elsewhere may also prove to be viable and the authors anticipate the emergence of a thriving new industry centred around the concept of core sunlighting.

Comparison to a more conventional approach

With these demonstration systems as evidence that core sunlighting is now practical, the authors carried out a design study to compare the capital cost, operating cost, and energy use in three representative buildings that have the same net area of leasable space, but use different methods of illumination.

Building A, the base design, has standard floor-to-floor spacing and is designed with solid walls (R-14 [i.e. RSI 2.47]) and standard double-glazed strip windows (R-1.6 [i.e. RSI 0.28]) at a height of 750 to 2100 mm (30 to 83 in.) above the floor. The windows provide a modest amount of daylighting in the perimeter spaces, but most of the lighting is provided by electric lights.

In contrast, Building B has increased floor-to-floor spacing and a ‘full-height’ glazed envelope to enable deep daylight penetration. It has a reasonably high-performance curtain wall system consisting of low-emissivity (low-e) coated, argon-filled, double-glazed units, with thermally broken aluminum frames. The spandrel extends at each floor level from 750 mm above the finished floor down to the underside of the ceiling below. The spandrel is assumed to have an insulation value of R-12 (i.e. RSI 2.11), while the glazing portion is assumed as R-5 (i.e. RSI 0.88) (resulting in a combined value for the spandrel and glazing of about R-6 (i.e. RSI 1.06). Due to the high ceilings and fenestration ratio, the electric lights in Building B need only be operated when daylight is not available.

Building C is identical to Building A, but it incorporates a core sunlighting system that enables the electric lights to be turned off whenever the sun shines. Figures 3 and 4 compare the design details for the three buildings.