Controlling airflow for a healthy building

Controlling air migration

Air barriers are designed to control the flow of air between a conditioned indoor space and an unconditioned outdoor space by:

- providing a continuous coating (or covering) over the entire building or individual unit;

- acting as a smoke, gas, and fire barrier between a garage or other fume sources and conditioned air; and

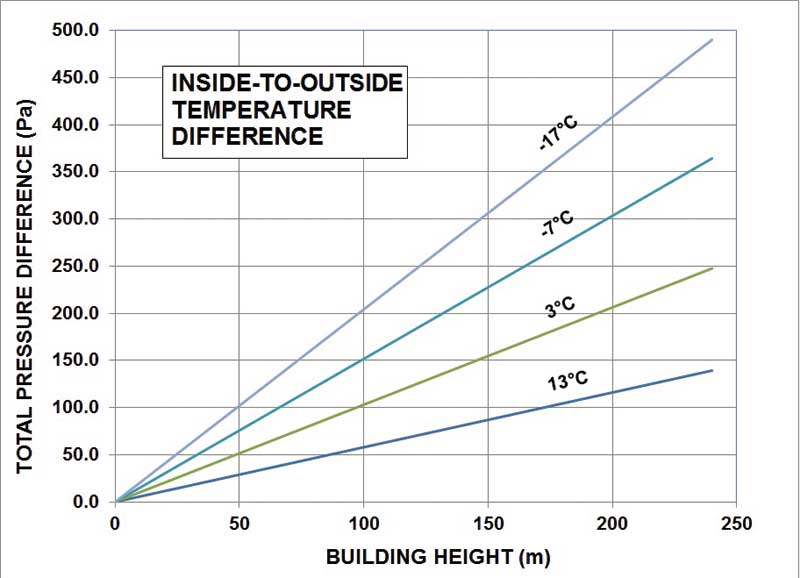

- resisting air pressure differentials that act on the air barriers externally and internally (i.e. pressure from HVAC fans).

To avoid confusion, this article is not going to cover vapour barriers, which are materials designed to prevent the diffusion of moisture through the surface on which it is applied. Vapour barriers and air barriers are not the same. An air barrier is designed to ‘breathe’ and therefore, is permeable. An air barrier sheet, for example, can be an air barrier and vapour-permeable. Other sheets can be an air barrier and vapour- impermeable. Use of these materials will depend on specific construction and building code requirements that are beyond the scope of this article. (For additional information on vapour barriers, Joseph Lstiburek’s “Understanding Vapour Barriers” is a useful resource. Visit buildingscience.com/documents/digests/bsd-106-understanding-vapor-barriers.)

The National Air Barrier Association (NABA) was founded in 1995 to bring the air barrier industry together to encourage proper research and development, standards and specifications, manufacturer and contractor licensing, installer training and certification, documentation and reporting, and a third-party audit process. The group’s membership includes contractors, manufacturers, design professionals, testing agencies, consultants, and utilities.

NABA has set the Canadian standard for air permeance—a measure of the volume of air that is permitted to pass through an area of substrate in a given time at a specified pressure difference across the coating. The units are normally given as either litres per second per square metre of surface (L/s•m²), or in imperial units of cubic feet per minute per square foot of surface (cfm/sf). Permeance, in the context of air barriers, is generally defined in three levels:

1. Air barrier materials must have a maximum permeance of 0.02 L/s•m² (0.004 cfm/sf) at a pressure differential of 75 Pa (1.6 psf). Examples include liquid coatings or manufactured sheets.

2. Assemblies using air barrier materials cannot have more than 0.2 L/s•m² (0.04 cfm/sf) at the same pressure differential. Referred to as an ‘air barrier assembly,’ one example would be a wall composed of concrete masonry units (CMUs) coated with an air barrier material and perhaps rigid foam insulation to mimic real-world conditions.

3. Building enclosures cannot have more than 2 L/s•m² (0.4 cfm/sf) over the same pressure differential. Referred to as ‘air barrier systems,’ they include the whole enclosure—from the latex interior wall paint to the exterior façade around the entire building. (For more, see NABA’s January 2013 Technical Bulletin, “Air Barrier Requirements in Canadian Building Codes and Standards.”)

The balloon example can again be used to dramatically illustrate air permeance. An average 305-mm (12-in.) latex balloon can hold about 14 L (0.5 cf) of air. For a building with exposed walls comprising CMUs, approximately 15 per cent of the volume of concrete, once cured, consists of empty space in the form of tiny pores, most with diameters smaller than a human hair. Compared to the size of the nitrogen and oxygen molecules found in air, however, the pores are enormous.

Tests have shown air permeance through unpainted concrete block can exceed 0.75 L/s•m² (0.15 cfm/sf) at a sustained pressure differential of 72 Pa (1.5 psf). (This comes from “Building Airtightness Requirements—Code Requirements for Commercial and Multifamily Building Airtightness Testing, City of Fort Collins.” For more information, visit www.fcgov.com/utilities/img/site_specific/uploads/2015-03-25-FtCollins-MFProtocol-ABT-PiePresentation.pdf.) If this pressure differential is sustained for more than an hour, enough air bleeds through 1-m2 (10.7-sf) section of concrete to fill about 193 latex balloons. When an air barrier coating is applied to this same surface area, the air permeance drops to less than 0.02 L/s•m² (0.004 cfm/sf), which, after an hour at that sustained pressure difference, would only fill about five balloons—a reduction of more than 97 per cent.