Construction and silicosis: What you need to know

by Nayab Sultan

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), an estimated 160 million people suffer from work-related diseases, with some two million dying annually as a result. About eight per cent of these occupational disease deaths can be directly attributed to respiratory complications, namely chronic obstructive pulmonary disorders (COPD), asbestos-related diseases (ARDs), pneumoconiosis, and silicosis. What exactly is silicosis, though, and what should design/construction professionals know to help reduce its impact on those in the industry?

Conservative estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO) estimate 46,000 annual deaths from exposure to harmful levels of respirable crystalline silica (RCS) dust before progression to silicosis and other diseases. However, with under-reporting and misdiagnosis being common, tens of millions remain vulnerable, including thousands of Canadian workers. Therefore, the actual number of deaths from silicosis is likely to be far higher, particularly in developing countries. This is then further increased by considering environmental exposures.

CAREX Canada, a national surveillance project for estimating the number of workers exposed to substances associated with cancer in the workplace, reports approximately 380,000 Canadians (93 per cent males) are exposed to silica, primarily in the construction sector. In contrast, the figures for asbestos stand at 152,000 for the same sector. According to 2011 cancer statistics from CAREX, 570 lung cancer cases (i.e. 2.4 per cent overall) were attributed to occupational exposure to crystalline silica across the country. (Exposure is considered moderate to high amongst specialist trade contractors and building construction professionals followed by the heavy and civil engineering construction industry in Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, and British Columbia, respectively.)

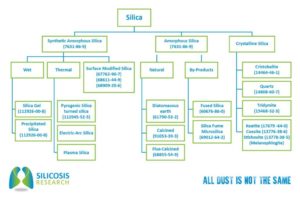

All dust is not the same

Images © Nayab Sultan

Respirable crystalline silica is a naturally occurring substance found in stone, rocks, sand, and soil, as well as in concrete, fly ash, asphalt, clay, brick, grout, clay and ceramic tiles, some composite materials, and some metallic ores. Shingles, mortar, plaster, drywall, and many products commonly found in construction projects across Canada. Figure 1 offers some examples, while Figure 2 gives a range of RCS commonly found in the Canadian building industry.

RCS is harmful to health when it is inhaled deep into the lungs. The dust that is particularly harmful is smaller than a fine grain of sand. To put this into perspective, the size of a period is about 200 to 300 μm (7.8 to 11.8 mils) in diameter, whereas the RCS dust is about 5 μm (0.2 mils)—so small the particles cannot be seen with the naked eye.

If a person is exposed to high levels of RCS, harmful effects and onset of acute respiratory conditions can start in as little as a few weeks, especially where exposed to particularly high grades of silica dust and with no or ineffective respiratory protective equipment.

There are less-harmful forms of silica dust (e.g. amorphous, diatomaceous earth, or silica gel) that are not recognized to lead to silicosis, lung cancer, or other known diseases commonly associated with RCS. That said, it is possible to chemically change amorphous silica at temperatures above 1300 C (2372 F), where it can transform into RCS.

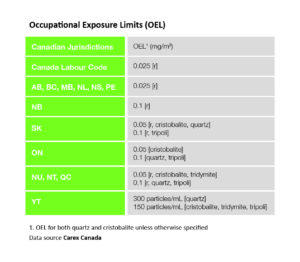

There are set standards regulatory authorities determine to be maximum levels of exposure before there is likely to be any significant harm. In Canada, this depends on the province (Figure 3).

Exposure needs to be monitored and the health of workers kept under surveillance to ensure levels are not harmful. Attempting to use sight to determine levels does not work—by the time a dust cloud is observed, levels are generally likely to be in excess of what is considered to be safe and of the province’s occupational exposure limit (OEL).

Image courtesy CAREX

What is silicosis?

The name silicosis is derived from the Latin word Silex or flint, and is associated with inflammation and scarring of the upper lobes of the lungs in the form of lesions. While symptoms related to asbestos may take between 10 and 50 years to manifest, the effects of silicosis can start within a short period as seen in the Hawks Nest Disaster (Figure 4). In this incident from the 1930s, hundreds of construction workers died as a result of acute silicosis and associated conditions due to exposure of high levels of RCS dust while building a tunnel through sandstone-based rock with little (or no) respiratory protection. Individual susceptibility is based on factors such as amount of dust, particle size, respiratory protective equipment worn, the individual’s overall health status, genes, and whether the person is a smoker.

In acute form (i.e. short-term, severe, or sudden), the symptoms are typically bluish skin, breath shortness, coughing, and fever. It is not uncommon for this to be misdiagnosed as pulmonary oedema (i.e. water in the lungs), pneumonia, or tuberculosis. Symptoms can continue to develop even after exposure has stopped. Other conditions can also occur, such as bronchitis, lung cancer, or arthritis.

So how can construction professionals work safely without being harmed? If the threat of exposure to RCS cannot be eliminated altogether, then there are a few control measures that may work in keeping dust to relatively safe levels. To ensure compliance with various legislative requirements, the local rules must be followed. Generally, they are based on the principles of occupational hygiene: assess, control, and review.