Combating building pressure at the door

By Alan D. McMurtrie, DAHC

Building pressure is an invisible, pervasive threat that puts projects at risk—and it all starts at the door. Accessibility, life safety, and energy efficiency are concerns in all buildings, but uncontrolled pressure can increase these hazards. The first line of defense begins with selecting the correct door closer.

Closers are commonly used in commercial structures to ensure doors are shut and securely latched, as well as to reduce airflow through the building. When the correct closer is in place, it can reduce the potential concerns caused by pressure differentials. To understand how building pressure can put buildings at risk and how closers can mitigate it, one should first explore what causes the phenomenon.

Building pressure causes

Building pressure is caused by a difference in temperature or pressure between two spaces separated by doors. As air pushes into or out of a building—moving from an area of high pressure to one of lower pressure—it exerts incredible amounts of force on the doors and can prevent door closers from properly functioning.

Sometimes referred to as stack pressure, these significant pressure differentials often occur between the inside and outside of a building, but can also create problems between adjoining rooms or wings of a facility. Corridors, atriums, and stairwells are particularly at risk. The more extreme the difference between interior and exterior temperatures, the greater the amount of pressure that will exist inside, predominantly in multistorey buildings.

Pressure differential is created primarily by three forces: wind, temperature, and the facility’s HVAC system.

Wind

Air is typically forced into a building on the side facing into the wind (i.e. the windward side), and pulled out on the side sheltered from the wind (i.e. the leeward side). Strong winds can create significant airflow through a building, dramatically increasing the amount of pressure in one area compared to another. The structure’s shape can also create swirling winds or irregular wind pressures that impact the amount of negative or positive building pressure. Positive pressure exists when the pressure inside a building or space is greater than the pressure on the outside. It can be beneficial in areas such as patient rooms, where it limits exposure to any outside germs or contaminants.

Negative pressure exists when the pressure inside a building or space is less than the outside pressure. This tends to make outswinging exterior doors difficult to open.

Temperature

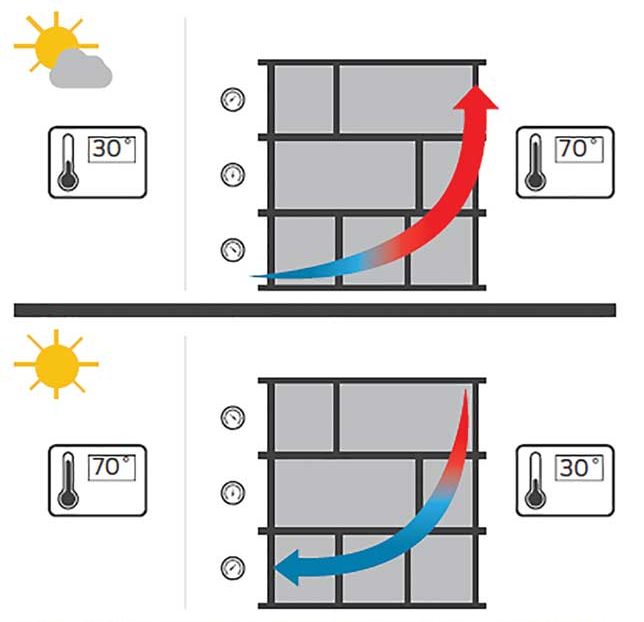

An extreme difference between interior and exterior temperatures can cause building pressure in a facility, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as the chimney or stack effect.

In parts of Canada, issues can arise with hotter temperatures in the summer, meaning stack pressure can occur in the building when the air-conditioning is going. This can impact not only perimeter doors, but also stairwells.

A significant amount of airflow can be created in such areas, where the lower density of warm air causes it to rise and displace cooler air. This also occurs due to the difference in air density between the interior of the building and the exterior.

For example, if the outdoor temperature is -1.11 C (30 F) and the indoor temperature is 21 C (70 F), this can create an excessive amount of negative pressure within the lower levels of the building, and a correspondingly high amount of positive pressure within the upper levels. The pressure difference pulls the cold outdoor air in at the lower levels and pushes the heated indoor air out at the upper floors. When it is warmer outdoors than indoors, the opposite happens, as explained in Figure 1.

HVAC systems

As buildings consist of numerous interconnected rooms of varying sizes and pressures, HVAC systems must attempt to equalize the temperature and pressurization of each by using fans to circulate and exhaust the air. Air will naturally flow from high-pressure areas to lower-pressure ones, meaning these systems are often used in highrise buildings to deliberately increase pressure within the lower levels of stairwells, helping to keep them free of smoke in the event of a fire.