Colour Considerations: Managing visual expectations for metal coatings

by Katie Daniel | May 22, 2015 10:23 am

[1]

[1]By Scott Moffatt

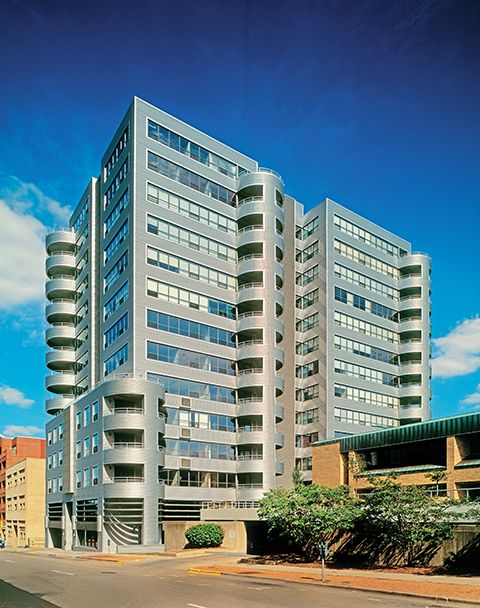

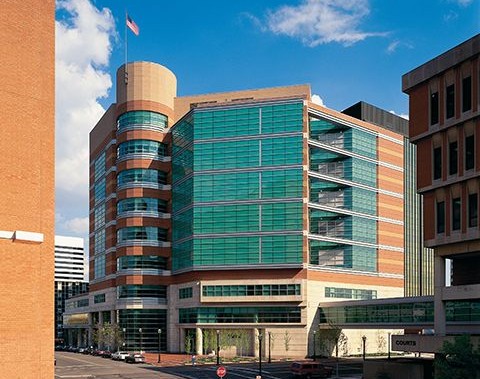

Metal coatings have come a long way. Not only have their protective and environmental qualities improved dramatically in recent years, but so have the range of colours and effects. Thanks to these new innovations and technologies, architects can choose from an extraordinary palette of decorative colours, glosses, and sheens for commercial office buildings, retail stores, and entertainment complexes.

While these developments are, on the whole, overwhelmingly positive, they also have heightened the need for more vigilant colour-matching and quality control measures on the part of coating applicators and their customers. As the number of coatings, glosses, and sheens have expanded, so have the opportunities for colour variation. Even subtle differences in hue, which may look negligible when building components reach the site, can be exaggerated when components are actually installed on a building.

This article is intended to help architects and other building professionals more effectively manage colour expectations so components arrive at their final location coated in the specified colour, and components produced by different coating applicators appear as a co-ordinated whole when installed on a building.

Avoiding the checkerboard effect

A new generation of coatings, incorporating natural materials such as metallics and micas, has helped contemporary architects create truly extraordinary buildings. Unfortunately, co-ordinating coatings across numerous building components can present difficulties that prevent architects from achieving their intended vision.

In most instances, the differences between the architect’s original vision and the finished coating on a building are minimal. In extreme cases, however, a number of small variations throughout the coatings process—from concept to finished product—can accumulate, producing noticeable and unacceptable visual differences among coated building components.

When installed on a building, these mismatched components may achieve a ‘checkerboard effect,’ which is a problem that can often be traced directly to the original colour specification. To minimize colour-matching problems at the specification phase, architects should be mindful of the following:

1. Colours chosen for a particular project are usually selected from a collection of printed chips or samples, then viewed in lighting conditions different from those in the field.

To achieve the most accurate match, colour samples should be viewed in what will be the coating’s finished building environment.

2. Time of day and time of year can also affect the appearance of individual colours.

Natural light is neither uniform nor constant, and its characteristics also will vary according to atmospheric conditions.

3. The height, angle, or distance from a light source can alter the appearance of a colour; so can its surrounding environment.

The colour on a building surrounded by trees will look different next to an open landscape, a highway, or another collection of buildings. This is also true of certain solid colours, micas, and metallics, which can reflect different appearances according to the surrounding light and the orientation of individual flakes.

4. The gloss and the surface character of the sample chip itself is important to consider.

One coating manufacturer may provide samples on galvanized steel substrate, while another may apply its coatings to an aluminum substrate. To ensure the truest colour representation, one should insist colour samples be coated on the actual substrate from which the building panel or extrusion will be manufactured.

[2]

[2]Applicators and application methods

Colour-matching problems are also common when multiple coating applicators are used. The methods of applying paint—and the equipment used to do so—can vary widely between them. Another variable is the shape of the metal substrate. The coil-coating process produces colours that look different from extrusion coatings, even when the formulations are exactly the same.

Operating conditions at the time of manufacture can also affect a coating’s final appearance. Temperature, humidity, the curing process, and how thick the coating is applied are variables that can fluctuate daily, even within the same plant. Colour differences can also be attributed to the line operator.

To minimize the potential colour differences related to these variables, architects and contractors should adhere to the following guidelines:

1. Limit the number of coating applicators used on each project. Lessening the suppliers reduces the chances for colour-matching and quality problems.

2. Once coating applicators have been selected, notify the coating manufacturer of who will be responsible for which building component. This will facilitate better colour co-ordination among the different applicators.

3. Use the primary applicator panel (i.e. the major component on the building—the highest percentage of visible painted metal) as the standard. This way, the coating manufacturer can make sure the standards for each coating applicator match one another. Do not use coil-coating standards for spray coatings or vice versa. Each application method should have its own individual standard.

4. For large projects, request sample ranges from each coating applicator. Use the samples to determine the capabilities of each applicator and apply that knowledge to more effectively manage the colour-matching/co-ordination process.

5. Adjust the colour match on coil coatings to the colour of the spray coatings. Since colour control is more exact with coil than with spray coatings, it is easier to establish a colour standard with the latter, and then formulate the former to match it. The only exception to this rule is for white or light-coloured coatings. In these cases, the coil coating should be used as the template since coil coatings are usually applied at a thinner film rate, which makes them more difficult to adjust.

|

Spectrophotometer Support |

| Trying to make important choices about colour can be a highly subjective exercise. For this reason, spectrophotometers are invaluable measurement tools that take much of the guesswork out of colour evaluation. Instruments that contain integrated spheres can even sort through layers of complexity (like fabric), and eliminate gloss from the equation so only pure colour is being evaluated.While computers can never fully replace the human eye, it should be noted not every human eye perceives or sees light or colour in the same way. One reason is age. The retina contains two types of photoreceptors: cones and rods, and people begin to lose the latter with age. Rods do not perceive colour, but are acutely sensitive to light and critical for night vision. This is why a 50-year-old driver needs twice as much light to see after dark as a 30-year-old.Spectrophotometers help level the playing field when making critical decisions about quality control and design by taking the selection beyond subjectivity and physiological differences of eyesight. |

[3]

[3]Understanding coated profiles

Profiles are extruded metal components used to construct curtain walls, louvres, and other decorative accents. They usually contain intricate details, including angles, edges, grooves, recessed areas, and other contours that make paint coverage difficult. Since paint thicknesses vary on these components, so does the colour consistency.

Metal thickness on profiles presents another challenge for coating applicators. For a coating to properly cure, the metal underneath it must reach a minimum temperature. In places where the metal is thicker, it takes longer for the metal to reach the prescribed temperature. When that happens, pigments are exposed to heat longer. This can cause the coatings to ‘burn’ or discolour—a problem more commonly found with white or light-coloured coatings.

With these constraints in mind, the following are some recommendations for minimizing colour variation on profiles:

1. Understand the profile’s limits. Crevices and angles make complete coverage difficult and uniform coverage unlikely. If a profile demands complete coverage and uniform thickness or colour across all surfaces, consider a different configuration.

2. The same rule applies to thick profiles. Final colours on thick profiles may in fact vary slightly due to the extended curing requirements.

3. If colour-matching is paramount, avoid profiles with large differentials in metal thickness, such as parts with thin protrusions attached to thick walls. The temperature required to cure the thicker wall will ‘burn’ the coating on the thinner protrusion, creating a different colour on that part of the profile.

4. Before final approval, obtain a painted sample of the finished product from the coating applicator before the building material is painted.

Specifications often inappropriately require ‘perfection’ of finishes, but nothing is perfect. An attempt at a perfect coating appearance is also wasteful when it is in a location where observers cannot appreciate this level of quality due to distance or visual obstructions. In these instances, over-specifying is wasting the owner’s money.

Variations in the coating process

Beyond colour and the quality of coating applicators, there are countless variables in the coating process itself. No matter how stringent or demanding, no quality control program can account for all the contingencies involved in the coatings process.

[4]

[4]In fact, numerous factors affecting colour consistency are beyond the coating manufacturer’s control. For instance, pigment manufacturers set strict tolerances for the formulation of their products. Yet, these pigments still present inherent variations that are ultimately passed on to the coating applicator. Similar variability may apply to the micas and metallics. It is difficult to enforce strict tolerances for these products simply because they are based on ‘natural’ raw materials.

Comparatively speaking, the impact of these raw material variations is small. The greatest potential for colour-matching problems is found in the four major variables related to the application process. They are:

- batch variation;

- metal substrates;

- paint technology; and

- panel installation.

[5]

[5]Batch variation

Problems with batch variation arise when coatings are produced by more than one coating manufacturer, or if one coating manufacturer has to produce multiple batches of a coating to complete a job. Typically, variation between batches is minimal and minor differences can be masked through proper application of the product. Nevertheless, there are several steps architects and contractors can take to minimize potential batch variation problems.

1. Determine the amount of coating required up front. This may enable the manufacturer to produce all the coatings in a single batch, eliminating batch-to-batch variation. If a single-batch approach is impossible, the next best solution is to minimize the number of batches needed.

2. Reduce the number of coating manufacturers and coating applicators. Trying to match batches and standards among different coating manufacturers and coating applicators is extraordinarily difficult. Raw materials vary from one coating manufacturer to another, as do manufacturing processes, colour-measuring standards, and equipment. When possible, specify all coatings from a single coating manufacturer and coating applicator.

3. Try to get all metal painted at the same time. Again, one batch of paint with a single application run—using the same operator in the same operating conditions—is the most efficient way to eliminate variables.

4. Finally, if additional coatings are needed to complete a job, always specify the new order matches the original batch number used. This gives the coating manufacturer and coating applicator a consistent reference to use during the production process.

[6]

[6]Metal substrates

When coatings are applied to metal, two variables can affect their final appearance. The first is the type of metal used (most commonly steel or aluminum). The second is how the metal was pre-treated. To promote colour consistency across all the substrates used on a particular building, the architect or contractor should make the coating manufacturer(s) aware of all the different metals being coated. This allows the coating manufacturer to match colours across the entire range of substrates for a given project.

The architect or contractor should also verify with the coating manufacturer(s) their product has been engineered for use over the desired substrate(s), and that it is compatible with the pre-treatment method used by the coating applicator.

Paint technology

Coatings are formulated using various base resins and pigments. When coatings are mixed, even subtle differences in colour and metamers (i.e. pigmentation effect that causes the same colour to look different under different light sources) can be exposed. This is why viewing colour samples under actual lighting conditions is vital.

Paint chemistries can also change according to the performance specification required for the coating. The same pigment deposited in a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) coating will usually produce a colour that looks different from the same pigment in an acrylic coating.

For this reason, it is essential architects and contractors communicate to their coating manufacturers all performance specifications related to a project. If more than one performance specification is required, colours must be matched in each resin chemistry before application.

[7]

[7]Panel installation

Even when the three variables detailed above are closely monitored, problems can still arise during installation to produce the checkerboard look. In fact, such problems are more likely to occur during installation than at any other part of the process.

In most instances, the primary failure is ‘directionality.’ A single panel coated with the same paint may be cut into six different pieces prior to installation. If one or more of the pieces is oriented in a different direction from the others, the uniformity of the entire panel can be disrupted.

This effect can be greatly exaggerated in panels and extrusions coated with micas and/or metallics. This is because the pigments and flakes on a given panel (or collection of panels) will lay in a certain direction. If these panels are cut and laid ‘opposite to the grain,’ the colour will appear incongruent.

For this reason, proper panel directionality during installation is essential. Here are several steps architects and contractors can take to help ensure good panel matching:

- Make sure the coating applicator marks the panel with a directional marking, typically an arrow. This will help the installer orient the panels properly when they are being attached to the building.

- Avoid putting sheet panels and extrusions in the same plane. Since they are coated using different processes, colour-matching is difficult. If these components must be in the same plane, design the structure to include a visual break. This will help mask any colour differences that exist between the two elements.

- When panels arrive onsite, have the installers inspect and segregate them by colour. That way, when the panels are actually being attached to the building, the installers can use similar colours on specific sections of the building, using lighter colours on the lower floors of a building, for instance, and darker panels on top.

- Finally, if two adjacent panels appear to be mismatched, do not install them. Find panels that match or call the applicator to address the issue.

Conclusion

As detailed throughout this article, the ability to manage colour expectations for metal coatings requires architects and general contractors to be well-versed in every step of the process, from how to view samples to how finished panels are installed on the jobsite.

For design/construction professionals seeking to minimize both risk and the demands on their time, the best solution is to work with a trusted and proven coatings company that maintains a network of certified applicators who are knowledgeable about their products and trained to meet exacting standards for colour consistency, application quality, installation quality, and customer service.

By working with both experienced coatings manufacturers and their certified suppliers, architects and general contractors do more than minimize opportunities for checker-boarding—they also find a trusted working partner they can count on through every step of the design, specification, and building process for both the immediate project and others to follow.

Scott Moffatt is PPG’s market manager for building products, and has 36 years of experience in the coatings industry, encompassing assignments in sales, product management, and marketing. He is a board member of the Metal Roofing Association (MRA), and a member of the Metal Construction Association (MCA), Metal Building Manufacturers Association (MBMA), National Coil Coater Association (NCCA), American Architectural Manufacturers Association (AAMA), and the Cool Roof Rating Council (CRRC). Moffatt can be reached at moffatt@ppg.com.

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/colour_PPGX7714.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/colour_PPGX3816.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/colour_PPGX4859.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/colour_PPGX4194.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/colour_PPGX11233.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/colour_PPGX11221.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/colour_PPGX10316.jpg

Source URL: https://www.constructioncanada.net/colour-considerations-managing-visual-expectations-for-metal-coatings/