Code development’s past, present, and future

By Robert Rymell, P.Eng., C.Eng., CSC

You are probably thinking, “Oh great, another article about codes.” However, it is always surprising so many in the design/construction industry do not fully understand how building codes work (nationally and provincially), how they are developed, and how they impact individual firms.

In order to keep this discussion manageable, the national codes, their development, and their interrelation with the provincial (and sometimes territorial) documents and authorities will be considered here. There will be no venture into the world of technical issues.

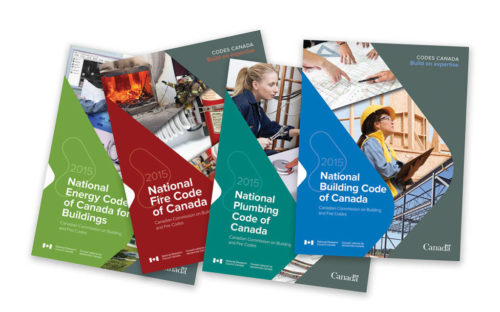

The term ‘national codes’ refers to the National Building Code of Canada (NBC), National Fire Code of Canada (NFC), National Plumbing Code of Canada (NPC), National Energy Code of Canada for Buildings (NECB), and National Farm Building Code of Canada (NFBC).

The national codes development process is carried out by the Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes (CCBFC) and hosted at Codes Canada at the National Research Council (NRC) in Ottawa. NRC provides the technical advisory staff, as well as document and financial management of the process.

CCBFC is a group of individuals volunteering from across the country, representing regulators, industry sectors, general interest groups, and all geographic regions, with the intent to make the membership matrix as balanced as possible. Members of the Commission are appointed by NRC and membership is re-evaluated every code cycle. The Commission is responsible for policies and procedures of the code development system. This involves setting the scope of all documents (i.e. what codes should address), setting priorities (i.e. which tasks need to be done) and reviewing and improving the process (i.e. how the codes are developed). Since the Commission only meets once a year, its Executive Committee regularly advances this work, while being answerable to CCBFC.

Division B of each of the national codes contains their technical requirements. The work of writing the codes and revising or developing new technical requirements is carried out by standing committees and their task groups. There are nine standing committees, which are divided by subject as follows:

- Earthquake Design (NBC Part 4);

- Fire Protection (NBC Part 3);

- Environmental Separation (NBC Part 5);

- Energy Efficiency in Buildings (NECB);

- Hazardous Materials (NFC);

- Structural Design (NBC Parts 4 and 8);

- HVAC and Plumbing (NBC Parts 6 and 7 and NPC);

- Use and Egress (NBC Part 3); and

- Housing and Small Buildings (NBC Part 9).

The standing committees are divided by general professional disciplines. However, many of the topics run across more than one part of the code, and CCBFC requires effective cross-committee coordination so all aspects of a topic are reviewed.

The Executive Committee functions as a standing committee for Divisions A and C, which contain legislative and administrative content—for example, defined terms or the objectives of the codes.

The provinces and territories participate in the codes development system either directly on CCBFC committees, or through the Provincial/Territorial Policy Advisory Committee on Codes (PTPACC). In this way, the priorities of the code work can be aligned with the priorities of the jurisdictions. PTPACC plays an integral part of the whole process; its partnership with CCBFC and NRC has lasted more than 75 years.

The codes are ever evolving as new requirements are developed, regardless of whether they were motivated by public interest, by provincial and territorial (PT) policy changes, or new technology. Anyone can ask for a change to the codes by submitting a code change request. Then, that request will be evaluated by standing committees to determine whether it has technical merit and whether or not it should be pursued.

To follow along with the concept of transparency, proposed changes to the codes go out for public comment for four out of every five years (there is no public review in a publication year). The standing committees review every public comment received and revise the proposed changes where warranted.

A significant change that occurred about a decade ago was the introduction of objective-based codes. This was done to provide a consistent means of evaluating and accepting alternative solutions to code requirements. Each technical requirement now has objectives, functional statements, and related intent statements attributed to it, which are more accommodating to innovative approaches than the code requirements. All codes, with the exception of NFBC, are now objective-based.

In order to fully comprehend the system, some history is also needed. There is a lot of documentation available on this subject, but suffice it to say NBC has been in place since the 1940s and has since been used increasingly across the country. (For more details and to order past editions, click here.)

The provinces and territories have the ultimate authority over building and fire safety regulation, and typically either adopt or adapt the national model codes. While all provincial and territorial codes match the national model codes’ content by at least 75 per cent, some provinces develop their own portions to address regional practice or specific policy goals—for example, the Ontario Building Code (OBC), which came into play in the 1970s. Although other provinces, such as Québec, Alberta, and British Columbia, also enact their own codes, the level of uniformity among these provincial codes and the national model codes is very high. Even further to this, certain municipalities such as Vancouver have their own codes.

Until very recently, certain provinces and territories had not formally adopted any national model codes, but municipalities in these jurisdictions tend to adopt the national model codes themselves.

To add to the possible confusion, there are national and provincial fire, plumbing, farm, and energy codes—each of which may or may not be in place in any particular province or territory. Further, national codes are generally published on a five-year cycle, and provinces and territories typically adopt with a six- to 18-month delay, which means a particular region may or may not have the most recent version of the national codes in place. Unfortunately, this results in some confusion as to what rules are in place and where. As the designer, it is your responsibility to find out. (To read which provinces and territories have enacted which codes, click here.)

Moving forward, this complex situation has been recognized and work is taking place to harmonize codes across Canada. The costs of code development are now borne by various stakeholders, including provinces and territories, as well as the sales of national and some provincial codes. Resolution of that aspect can become a very complex discussion and is driven by the political will of those involved.

Understanding we live in a very large country with extremes in geographic and climatic conditions, as well as varying policy differences, even a harmonized code may still need local customization to deal with those local policies and conditions. How this finally emerges is yet to be seen. In the meantime, changes are inevitable, and recently national policy initiatives have been announced that have a direct and significant impact on the current codes.

The quickest change required is the discontinuing of the use of asbestos in Canada by next year. In order to meet the timeline stipulated by the federal government and still follow the rigorous code development process, the appropriate changes must be determined and changes proposed immediately.

Globally, climate change has come to the forefront. In Canada, climate change resiliency is the terminology being used for adapting buildings, infrastructure, and communities to better respond to climate change. The federal government has developed a roadmap for moving the country forward and called it the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. This edict has caused a significant review of codes from the viewpoints of climate change mitigation, such as reducing energy use, water use, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The Pan-Canadian Framework also prompted NRC and CCBFC to review how buildings and infrastructure could be built to resist changing climatic loads and extreme weather events better.

As such, advancing NECB has resulted in a policy whereby all new buildings will be required to be ‘net-zero-energy-ready’ by 2030. To achieve this goal while simultaneously respecting the fact the provinces and territories are at different levels of building energy efficiency requirements supported by their respective own policy goals, NECB will be published with several tiers of different energy performance levels for buildings. This is so the end goal of net-zero energy buildings can be realized in timeframes deemed appropriate by each province/territory within the next 13 years.

To truly reduce GHG emissions in Canada, however, all buildings—including existing ones—must be considered regarding how they are heated and how they use energy in general. CCBFC and PTPACC—supported by NRC and Natural Resources Canada (NRCan)—are looking into possible means of dealing with those issues in existing housing and buildings.

A CCBFC/PTPACC Joint Task Group on Alterations to Existing Buildings has been tasked with looking at how to deal with all issues surrounding code compliance of existing buildings and houses. Since climate change resiliency does not just affect buildings, a means to codify or standardize Canada’s infrastructure is also being investigated.

Similarly, another social aspect quickly becoming of great importance is accessibility. It can become a contentious issue from the point of view of defining what accessibility means and to what level access has to be provided. It should be noted the provinces and territories have made this a high priority. Currently, the various jurisdictions are developing policy to deal with accessibility, which will inevitably lead to code changes.

It can be seen the development of codes is a rather complex topic and subject to social, economic, and political influences as well as ever-increasing safety requirements. The climate change resiliency aspects further this complexity and keep the codes evolving.

Robert Rymell, P.Eng., C.Eng., CSC, is president of RBS Consulting Engineering Group in Innisfil, Ont. He is a professional engineer and a registered consulting engineer licensed to practice in Ontario, Alberta, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia. Rymell is a member of the executive committee of the Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes (CCBFC), as well as the Toronto Chapter of CSC, the Ontario Building Envelope Council (OBEC), and the National Building Envelope Council (NBEC). He can be contacted via e-mail at r.rymell@rbsengineering.ca.

Robert Rymell, P.Eng., C.Eng., CSC, is president of RBS Consulting Engineering Group in Innisfil, Ont. He is a professional engineer and a registered consulting engineer licensed to practice in Ontario, Alberta, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia. Rymell is a member of the executive committee of the Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes (CCBFC), as well as the Toronto Chapter of CSC, the Ontario Building Envelope Council (OBEC), and the National Building Envelope Council (NBEC). He can be contacted via e-mail at r.rymell@rbsengineering.ca.