Brick by brick

The enduring value of clay masonry

Imagine walking through a historic Canadian neighbourhood surrounded by century-old buildings with facades as solid and vibrant as the day they were constructed. What is the secret behind their resilience? The answer lies in a centuries-old material: clay masonry. This material has been the backbone of architecture across civilizations and continues to prove its value in modern Canadian design. For homeowners, architects, and designers today, clay masonry represents more than just a traditional building material; it offers an ideal combination of sustainability, timeless esthetics, and superior technical performance, making it the premier choice for facades in challenging climates.

From ancient mansions to the enduring appeal of historic townhouses, clay masonry has been a fundamental building material for centuries. The resilience of these structures, many of which stand tall to this day, speaks to the inherent durability of clay. In the Canadian architectural landscape, where climate and environment demand high-performance materials, clay masonry remains a go-to choice. For designers and architects, selecting the right facade material is about more than appearance; it is about technical details that ensure longevity, resilience, and sustainability. Clay masonry has earned its place as a leading choice for facades in Canada, offering a unique blend of practicality and enduring beauty.

The technical superiority of clay brick

One of the key advantages of clay masonry is its impressive compressive strength. Most Canadian masonry manufacturers produce clay bricks with an average compressive strength of 60 MPa (8.7 ksi) or higher, making them exceptionally strong and durable. This compressive strength is significantly higher than the average block on the market, surprising many who discover this fact. This strength is crucial in a country where buildings must withstand various environmental challenges, from heavy snowfall to high winds. The robust nature of clay bricks allows them to support significant loads while maintaining structural integrity over time.

Further, facades with clay bricks exhibit excellent durability, have great sound insulation, facilitate moisture management, and show remarkable thermal lag. Their high thermal mass enables buildings to absorb, store, and gradually release heat, contributing to energy efficiency. In the winter, homes stay warmer longer without excessive heating, and clay masonry helps keep interiors cool in the summer. As climate change drives fluctuations in temperature and increases the need for energy-efficient buildings, the thermal properties of clay bricks are invaluable.

Durability

Durability and longevity are crucial considerations when constructing buildings that stand the test of time. The durability of clay bricks is nothing new but not talked about often. For thousands of years, civilizations have used clay bricks to construct monumental structures that still stand today. These historical examples showcase the material’s resilience to weathering, environmental factors, and even seismic events:

- The Great Wall of China: Stretching more than 20,921 km (13,000 miles), much of the Great Wall is constructed from clay bricks. It has endured for more than 2,000 years, with sections still standing strong despite natural and man-made wear.

- The Alhambra, Spain: A stunning example of architecture, the Alhambra is made from clay bricks and remains a well-preserved masterpiece more than 600 years after its construction.

- The Sumerian Ziggurats, Iraq: Some of the world’s oldest monumental structures, these massive, stepped pyramids were built using mud bricks, a form of clay brick, around 4,000 years ago. Despite their age, many ziggurats are still visible today.

- McMartin House, Canada: Located at 125 Gore Street in Perth, Ont., this is a remarkable example of Loyalist Georgian architecture infused with American Federal style elements. Built in 1830 for Daniel McMartin, a prominent barrister and member of the Tory elite, this brick and stone house reflects the wealth and social ambitions of its era. Distinguished by its intricate detailing, cupola, and lanterns, the house symbolizes the craftsmanship and durability of traditional masonry. Designated a National Historic Site in 1972, it stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of clay brick and stone construction in preserving Canada’s architectural heritage.

- The Grange, Canada: Built in 1817, the structure is a testament to the enduring craftsmanship of clay brick masonry. As the oldest remaining brick house and the 12th oldest building in Toronto, it exemplifies clay brick’s strength, durability, and timeless esthetic. The house reflects the architectural heritage of the period. It showcases the historical significance of clay brick as a resilient and lasting building material capable of withstanding the test of time while maintaining its charm.

Many of these structures are still intact centuries later, demonstrating the inherent durability of clay bricks. Their ability to resist environmental factors, pests, and physical wear makes them an ideal building material for enduring architecture. Modern structures such as The Grange and McMartin house highlight clay bricks’ exceptional resistance to environmental stressors and their low maintenance needs in Canada. This durability factor significantly reduces lifecycle costs, making clay bricks a sustainable and economical choice.

Fire resistance

While visiting a friend’s place one weekend, the author noticed something unexpected. Known for his hands-on skills, the friend had built a makeshift barbecue using clay bricks. “I don’t have a proper grill,” he chuckled, patting the bricks. “But these can take the heat.” Curious, the author watched as the bricks withstood the intense flames without cracking or crumbling. This simple observation sparked a question: Are clay bricks actually fireproof?

This moment led to a deeper appreciation of the fire resistance of masonry. For centuries, clay bricks have been relied upon for their ability to endure extreme conditions, providing safety and stability in countless structures. Their enduring role in fire-resistant design continues to inspire architects, engineers, and designers.

Clay bricks’ fire resistance lies in their composition and manufacturing process. When fired at temperatures exceeding 1,000 C (1,832 F), they develop a dense and durable structure capable of withstanding extreme heat. They do not burn or release toxic fumes, and their solid form minimizes heat transfer, significantly slowing the spread of fire, even under prolonged exposure to high temperatures.

Standards and fire resistance ratings

Fire resistance ratings are determined using rigorous tests mentioned in CAN/ULC S101, which measure an assembly’s performance under fire conditions. This fire endurance test is the Canadian version of the ASTM E119 fire test used in the United States. In Ontario, designers refer to the Supplementary Standard SB-2 of the Building Code, which provides guidelines for clay bricks. For example, a 90-mm (3.5-in) standard clay brick unit, which is 80 per cent solid, is rated to resist fire for one hour. With thicker walls or multi-wythe assemblies, these ratings can exceed four hours, offering versatile solutions for fire-safe construction.

Clay bricks are a trusted material in fire-resistant construction. They are frequently used in walls and paired with insulation/fire retarders to limit the spread of flames in buildings and, in some countries, as load-bearing walls that combine structural support with fire containment. Their high thermal stability makes them ideal for industrial furnaces and other high-temperature applications. Similarly, using them as veneers also lowers the risk of fire jumping from one building to another.

Effectiveness during a disaster

Fire generally spreads through four mechanisms: conduction, convection, radiation, and direct flame contact. Clay bricks demonstrate effectiveness in mitigating fire spread against each of these methods:

- Conduction—Clay bricks are highly effective at resisting heat transfer through conduction. Their high density and porous mass absorb heat slowly, making them an excellent barrier to prevent the rapid spread of fire through walls. Unlike metals or combustible materials, clay bricks do not conduct heat efficiently or burn, containing the fire within a limited area for longer durations, providing enough time to take necessary actions. Clay bricks are non-combustible and maintain structural integrity even when exposed to direct flames. Unlike wood or synthetic materials, clay bricks neither ignite nor produce toxic fumes, making them dependable for walls and veneer applications.

- Convection—While clay bricks do not directly stop convection currents, as these involve air movement, they play a crucial role in sealed, fire-rated wall assemblies. By minimizing gaps and voids, clay bricks reduce the pathways for hot air to flow, limiting the spread of fire through air currents to adjacent spaces or buildings.

- Radiation: Clay bricks serve as a protective barrier against heat radiation. Their surface reflects or absorbs radiant heat, preventing nearby combustible materials from reaching their ignition temperature. This makes clay bricks ideal for firewalls or as barriers in high-risk areas.

According to the study by Santarpia et al.,1 temperatures during building fires can vary significantly, often exceeding 500 C (932 F) during the post-flashover phase and reaching up to 1,200 C (2,192 F) in high fire-load conditions with limited ventilation. Fires involving hydrocarbon fuels can generate even higher temperatures, surpassing 1,100 C (2,012 F). Since most clay bricks are fired at temperatures ranging from 1,000 C to 1,200 C (1,832 to 2,192 F), they are well-equipped to withstand such extreme conditions.

Future enhancements in fire resistance through research

A study by Heikal et al. (2023)2 explored the benefits of polymer-impregnated clay brick composites, highlighting that the inclusion of methyl methacrylate (MMA) polymers significantly enhanced the fire resistance, compressive strength, and durability of these materials. The polymer impregnation process fills the micropores within the clay matrix, making the structure denser and more resistant to heat-induced cracks. The study also suggested the compressive strength of the polymer-treated composites increased after thermal treatment, showcasing their enhanced resilience to fire and heat.

Thermal mass

Energy efficiency in modern buildings begins with the building envelope, which is a critical factor for influencing thermal performance. Often referred to as the structure’s “first line of defence,” the envelope regulates heat transfer, maintains a comfortable indoor environment, and lowers energy consumption. However, if this first line is weak, other building systems bear additional loads, increasing energy costs and reducing efficiency. A high-performance envelope ensures less energy is required to maintain desired indoor temperatures, reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and contributing to sustainability goals.

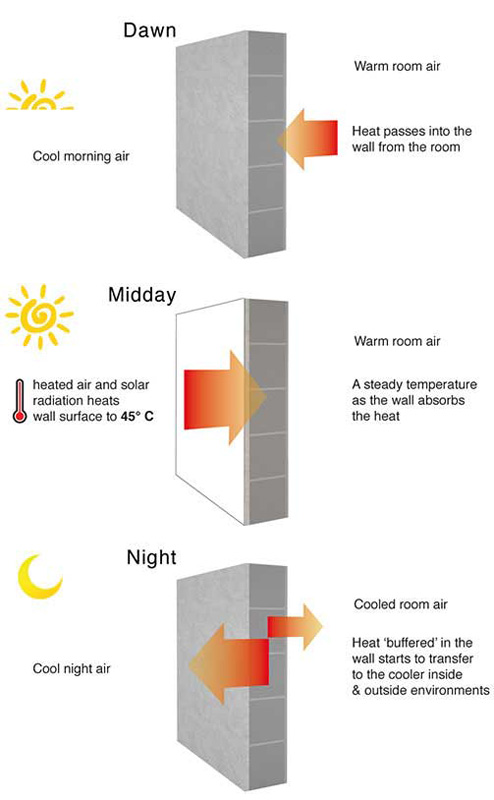

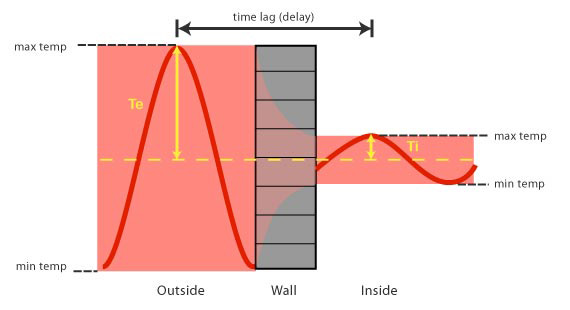

Thermal mass refers to a material’s ability to absorb, store, and gradually release heat. This is the property at which high-density materials, such as clay brick, excel. During the day, bricks absorb heat from sunlight, preventing rapid temperature surges indoors. As temperatures drop at night, they release the stored heat, maintaining a stable indoor environment. This phenomenon, known as thermal lag, helps moderate temperature fluctuations, reduces HVAC loads, shifts heating and cooling demands to off-peak hours, and lowers energy costs. Historic masonry buildings exemplify the enduring benefits of thermal mass, often maintaining comfort even without additional insulation. However, modern clay masonry design, paired with insulation, is the best possible assembly that supports thermal lag and maintains a comfortable living space.

The primary reasons for thermal mass here are high density and porosity. These properties allow clay bricks to store significant amounts of thermal energy. Unlike lightweight materials, clay bricks perform well under real-world, dynamic conditions. Their ability to delay heat transfer is particularly beneficial in climates with substantial temperature variations between day and night. In addition to their density and robustness, clay bricks maintain their thermal properties for decades, ensuring consistent performance over a building’s lifespan.

Understanding heat transfer in brick masonry

Fire, a function of heat, signifies that heat moves similarly to fire, as discussed earlier, through molecules via conduction, convection, and radiation. In brick masonry, conduction is the dominant mechanism. The effectiveness of bricks in slowing heat transfer depends on material properties such as:

- Thermal conductivity (k)—Measures a material’s ability to conduct heat.

- RSI-value (R-value)—Indicates thermal resistance or a material’s ability to impede heat flow.

- U-factor—Represents the rate of heat transfer through a material assembly.

Brick masonry, with its naturally high RSI-values (R-values), ensures minimal energy loss when designed and detailed thoughtfully.

Minimizing thermal bridging

Clay bricks also help in reducing thermal bridges. Thermal bridging occurs when highly conductive materials, such as steel, create pathways for heat loss. Thermal bridging in brick masonry walls is minimal per square metre. The primary areas where thermal bridging may occur in a masonry veneer wall are the brick ties and the shelf angle. Interestingly, these are not specifically masonry issues but design challenges. Several products are available on the market to mitigate steel thermal bridges further. Many designers are also using masonry behind the shelf angle to address thermal bridging at the anchorage point, showcasing the efficiency of masonry.

Sound insulation

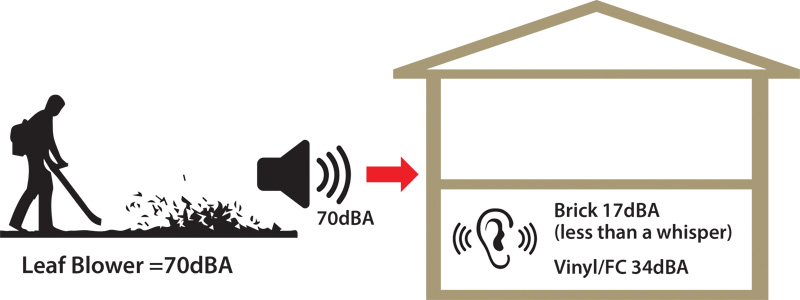

Sound insulation is critical for ensuring privacy and minimizing noise pollution when creating comfortable and functional spaces. Clay brick has proven to be a great choice for sound insulation, offering numerous benefits for residential and commercial buildings.

Understanding sound insulation

Sound insulation, also known as sound transmission loss, is a material or building assembly’s ability to resist sound passage from one side to the other. This property is essential for reducing unwanted noise and ensuring privacy between the enclosed space and surroundings. It is crucial to differentiate sound insulation from sound absorption. Sound absorption refers to the ability of materials to absorb sound waves, reducing reverberation within a room. While both properties are important, sound insulation is the focus here, as it directly impacts how well a wall assembly can block sound from passing through.

Sound Transmission Class (STC) rating

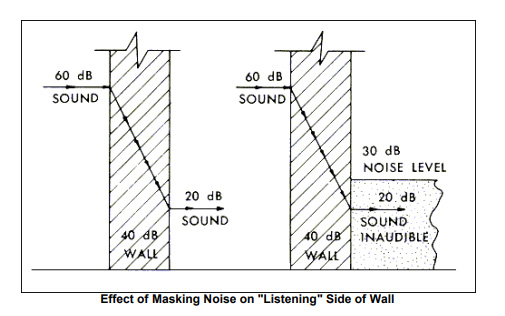

Sound transmission loss is typically measured in decibels (dB) to evaluate a material’s effectiveness in blocking sound. The result is often represented by an STC rating, a single-number rating that quantifies how well a building element, such as a wall, reduces sound transmission across a range of frequencies. The higher the STC rating, the better the material’s ability to block sound. An STC rating of 50 or higher is considered excellent for sound insulation, as it can reduce most speech or common sounds to an inaudible level. According to a study conducted at Riverbank Acoustical Laboratories, various clay masonry walls demonstrated impressive STC ratings, showcasing the material’s effectiveness in soundproofing.

Factors contributing to clay brick’s sound insulation

- Mass and density: The weight of clay brick walls, measured in pounds per square foot (psf), contributes to their ability to block sound. Heavier materials tend to prevent sound waves from passing through because they absorb and dissipate the energy of the sound.

- Wall configuration: The thickness and construction of the brick wall also impact its sound insulation performance. Thicker walls or those incorporating multiple layers, such as the composite walls, are even more effective in reducing sound transmission.

- Structural integrity: The solid construction of clay brick walls, including proper mortar joints and well-curated design, enhances their soundproofing performance. Staggered joints and high-quality masonry contribute to the overall effectiveness of the wall in blocking sound.

How clay brick performs in sound insulation

Clay brick walls have consistently demonstrated superior sound insulation qualities. The Riverbank Acoustical Laboratories conducted numerous tests on different types of masonry walls, with clay brick and structural clay tile options performing exceptionally well in sound transmission loss. The results from these tests underscore the effectiveness of clay brick in creating quieter, more private spaces.

These examples demonstrate clay brick’s robust sound insulation properties. The STC rating ranges from 45 to 59, depending on the wall configuration. The higher the STC rating, the more effective the material is at reducing sound transmission. This data can be found in Ontario Building Code section 9.11 (note A-9.11).

While many materials are available for soundproofing, clay brick consistently outperforms other common materials, such as gypsum board or lightweight drywall, in terms of sound insulation.

Moisture management

Moisture management is critical in clay brick construction, particularly for facades exposed to weather. Clay brick’s natural properties and the design of masonry systems enable effective moisture control, ensuring durability, performance, and longevity.

Moisture can enter a wall through several pathways, which may compromise the structure’s integrity. Rainwater penetration occurs during heavy rainfall or wind-driven storms when moisture infiltrates through small gaps or imperfections in the brick veneer or mortar joints due to wind pressure. Additionally, water can be drawn into the brick or mortar via capillary action, especially in prolonged wet conditions, as moisture is absorbed through small pores.

Condensation is another common issue, where warm, moisture-laden air from inside the building migrates into the wall cavity, where it cools and condenses, particularly in poorly insulated or inadequately ventilated walls. Groundwater can also wick upward through the foundation via capillary action if proper damp-proofing is not installed at the base of the wall. Further, improper detailing, such as missing or poorly installed flashing, weep holes, or vents, can lead to moisture infiltration. The vulnerable openings such as windows, doors, and roof-wall intersections are particularly at risk if not properly sealed and flashed. So before discussing how clay brick helps manage moisture, one must understand what happens if it is not managed.

Improper management of moisture in a clay brick wall can turn a sturdy, reliable facade into a crumbling mess faster than one can say “waterproofing fail.” Structural damage starts with freeze-thaw damage, where moisture sneaks in, freezes, expands, and turns the sturdy brick into a fragile mess. Further, efflorescence, that unsightly white powdery stuff on the surface, appears when excess moisture dissolves salts in the brick, signalling deeper moisture problems. As moisture continues to penetrate, it causes erosion of mortar joints, weakening the bond between bricks and leaving gaps that allow even more water in, accelerating the damage. Additionally, moisture can wick upward from the foundation, leading to capillary rise, which can cause cracking and settlement at the base of the wall, compromising the entire structure.

Beyond structural concerns, moisture leads to esthetic degradation. Staining and discolouration are common, along with the possibility of algae or mould growth, which looks unpleasant and is often costly and difficult to remove. Surface spalling occurs when trapped moisture causes the brick’s surface to flake off, permanently affecting the wall’s appearance. Thermal and energy efficiency may also suffer as moisture reduces the effectiveness of insulation, leading to increased thermal bridging where wet materials conduct heat more easily, raising energy consumption. High humidity levels also degrade indoor air quality, leading to damp, musty odours that fill the building. Without proper moisture management, building owners will face costly repairs and maintenance. Leaks due to improperly placed flashing, weep holes, or vents are expensive to diagnose and repair, and accelerated deterioration can result in premature replacement of bricks or mortar. Ultimately, unchecked moisture reduces the building’s lifespan, often necessitating extensive or complete restoration to restore structural stability.

Therefore, there needs to be a robust system for moisture management to tackle moisture issues. The clay brick rainscreen system uses an outer cladding layer of clay brick or any other masonry to protect the structure from direct exposure to rain and environmental elements. Behind the brick veneer lies an air cavity that facilitates drainage, ventilation, and the drying of any moisture that may penetrate the cladding. This combination of traditional material benefits and advanced engineering makes it the optimal choice for safeguarding structures over the long term.

Beyond moisture control, the durability of the clay brick rainscreen system is unparalleled. Clay bricks are naturally resistant to weathering, including UV exposure, rain, wind, and freeze-thaw cycles, making them ideal for protecting structures in harsh climates. Other sections of this article talk about pores or absorption of clay bricks, which are crucial parts of temperature regulation. Also, the pores are important in masonry to bond strongly with mortar. Clay bricks’ controlled porosity allows them to absorb moisture during exposure and gradually release it, preventing water buildup.

Key performance examples:

| Description | Sound transmission class (STC) | Wall thickness | Test number | Notes | |

| 102-mm (4-in.) face brick wall | STC 45 | 76–95 mm

(3–3.75 in.) |

TL 67-70 | ||

| 152-mm (6-in.) ‘SCR brick’ wall, with 9.5 mm (0.375 in.) gypsum board over 25.4-mm (1-in.) extruded polystyrene (XPS) insulation one face | STC 49 | 152–175 mm (6–6.87 in.) | TL 70-39 | Styrofoam placed with adhesive, spot applied 304.8 mm (12 in.) o.c. both vertically and horizontally; 22-mm (0.87-in.) gypsum board applied vertically. | |

| 203-mm (8-in.) face brick and structural clay tile composite wall | STC 50 | 203 mm

(8 in.) |

TL 67-65 | ||

| 254-mm (10-in.) face brick cavity wall, with 50.8-mm (2-in.) air space | STC 50 | 254 mm

(10 in.) |

TL 68-31 | Two wythes of masonry tied with metal wall ties. |

|

| 102-mm (4-in.) brick wall, with 5-mm (0.5-in.) sanded plaster, two-coat one face | STC 50 | 50.8–105 mm (4–4.125 in.) | TL 69-283 | ||

| 152-mm (6-in.) ‘SCR brick’ wall | STC 51 | 127–138 mm

(5–5.5 in.) |

TL 69-286 | ||

| 203-mm (8-in.) solid face brick wall | STC 52 | 203 mm

(8 in.) |

TL 67-68 | ||

| 203-mm (8-in.) solid brick wall, with 5-mm (0.5-in.) gypsum board on furring strips one face |

STC 53 | 229–235 mm (9–9.25 in.) | TL 69-287 | Collar joint filled with mortar; metal Z ties spaced at 610 mm (24 in.) o.c.; gypsum board applied vertically. | |

| 152-mm (6-in.) ‘SCR brick’ wall, with 5-mm (0.5-in.) plaster one face |

STC 53 | 152 mm

(6 in.) |

TL 70-70 |

How moisture exits the wall

Once moisture has entered the wall, the rainscreen system uses an air cavity and a series of components to direct the water out of the wall assembly and prevent it from damaging the underlying structure.

- Air cavity: The space between the brick veneer and the backup wall is critical for moisture management. This air cavity allows water that penetrates the brick veneer to drain downward toward the base of the wall. The cavity also facilitates airflow, which helps dry residual moisture over time.

- Flashing: Flashing is strategically installed at critical points of the wall, such as above windows and doors, at the base of the wall, and at any location that needs to be drained. Flashing directs water that enters the cavity toward the weep holes. It acts as a barrier to prevent moisture from travelling deeper into the structure and remaining there. This ensures the water exits the system rather than penetrating the internal building materials or staying in the wall system to cause harm. Flashing must slope toward the exterior and extend past the brick face to guide the moisture out effectively. It must have a drip edge to ensure the moisture is not falling back on the masonry.

- Weep holes: These are small openings on the base of the wall, often misunderstood by homeowners who mistakenly think the masons forgot to fill them with mortar—only to discover later just how wrong they were. These crucial openings are located just above the flashing, allowing water to exit the wall system. These small openings allow accumulated water in the cavity to drain out. Weep holes prevent moisture from pooling within the cavity, which could lead to issues such as mould, efflorescence, or structural damage. Properly spaced weep holes, typically no more than 610 mm (24 in.) apart, ensure efficient drainage of any infiltrated water.

- Vents: These are placed at the top of the wall. They may look similar to weep holes but serve a different purpose and are just as important. Unlike weep holes, homeowners do not typically clog vents, mainly because they are high up. Although not always required by code, vents are crucial in ensuring continuous airflow within the wall cavity. They help facilitate the evaporation of any residual moisture that remains after the flashing and weep holes have done their job. This airflow aids in drying out the cavity, preventing moisture buildup and preserving the integrity of the wall system. The combination of ventilation and drainage mechanisms ensures the wall cavity stays dry, reducing the risk of condensation or mould growth.

To summarize, effective moisture management is essential for maintaining the integrity, durability, and esthetic appeal of clay brick facades. The clay brick rainscreen system offers a comprehensive solution by combining the natural properties of clay brick with engineering features such as air cavities, flashing, weep holes, and vents. These components work together to prevent moisture infiltration, facilitate drainage, and promote airflow, ensuring that any moisture penetrating is effectively managed and evacuated.

Sustainability: A key component of clay masonry

Sustainability has become an important aspect of modern construction practices, and clay masonry could play a pivotal role in achieving a net-zero carbon-built environment. The only significant energy input for clay bricks occurs during the firing process, typically heating clay to more than 1,100 to 1,200 C (2,012 to 2,192 F). This is the only process that requires a considerable amount of energy, often sourced from natural gas. Currently, the manufacturing industry is making efforts to transition to low-carbon fuel sources, such as hydrogen, or to electrify production processes using renewable energy.

A highly ignored fact about clay masonry is that it is durable and recyclable at the end of its life. In 2023, Cheng H., in his paper on reuse of research progress on waste clay brick, indicated that around 90 per cent of brick construction waste can be recycled, usually down-cycled into aggregate for road fills or other construction uses. Canadian manufacturers often send their used bricks to be crushed and repurposed in tennis and baseball courts, exemplifying a circular economy approach that minimizes waste and resource consumption.

The recycling of waste clay bricks is gaining traction in sustainable construction. Waste clay brick (WCB) is classified as silicate solid waste, and its recycling holds significant environmental and social importance. Recent research has highlighted various applications for WCB, such as using it as recyclable coarse and fine aggregate in concrete and mortar, wall materials, and as a raw material or additive in producing recyclable cement.

Studies have shown that WCB can serve as a supplementary cementitious material, positively impacting the physical mechanics, deformation, and durability of cementitious materials. Additionally, WCB has been explored as an environmental material capable of eliminating fluorine, ammonia, nitrogen, and phosphates from wastewater, showcasing its versatility beyond construction.

Research also suggests grinding brick waste into recycled brick powder (RBP) and using it instead of cement is a feasible method to create sustainable construction materials. RBP is rich in silica (SiO2), alumina (Al2O3), and iron oxide (Fe2O3), exhibiting pozzolanic activity that can enhance the properties of cement-based materials. By partially replacing Portland cement with RBP (typically five to 15 per cent), the final product can improve workability, mechanical strength, and durability. This approach not only conserves landfill space by reducing the accumulation of brick waste but also decreases the concrete industry’s reliance on traditional Portland cement, thereby supporting the sustainability of construction materials and promoting global prosperity.

Conclusion

In summary, clay masonry is an exceptional choice for facade materials, combining superior technical performance with sustainability and esthetic appeal. Its strength, thermal efficiency, and recyclability make it a critical component of modern building practices, particularly in Canada’s unique climate challenges.

As the industry continues to evolve, brick masonry’s timeless appeal and unmatched performance make it a cornerstone of sustainable architecture. From traditional heritage buildings to cutting-edge designs, clay bricks’ potential as a holistic energy solution is boundless. By embracing this material’s strengths, architects and builders can craft structures that exemplify efficiency, resilience, and beauty.

Notes

1 Refer to Santarpia, L., Bologna, S., Ciancio, V., Golasi, I., & Salata, F. (2019). Fire Temperature Based on the Time and Resistance of Buildings—Predicting the Adoption of Fire Safety Measures. Fire, 2(19). DOI: 10.3390/fire2020019.

2 See Heikal, M., Amin, M. S., Metwally, A. M., & Ibrahim, S. M. (2023). Improvement of the performance characteristics, fire resistance, anti-bacterial activity, and aggressive attack of polymer-impregnated fired clay bricks-fly ash-composite cements. Journal of Building Engineering, 55, 107987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107987

3 Original image from GreenSpec.

4 Original image from Brick Industry Association (BIA).

References

- Cheng, H (2023). Reuse research progress on waste clay brick. College of Civil Engineering, North China University of Technology, Beijing.

- Bricks and net-zero building. Wienerberger UK. Retrieved from Wienerberger UK (2023).

- Clay brick could be the turning point in helping to decarbonize construction (2023). Retrieved from BM Careers.

- The role of bricks in achieving net-zero carbon emissions in construction (2023). Retrieved from The Independent.

- Research progress on recycled clay brick waste as an alternative to cement for sustainable construction materials (2023). Journal of Construction Materials Research.

Author

Aarish Khan, B.Tech, MASc, is a member of the technical services department at Arriscraft Canada Brick, a leading masonry manufacturing firm. He specializes in full bed and thin-clad masonry made up of clay, calcium silicate, and limestone. Khan holds a bachelor’s degree and a master of applied science in civil engineering, with expertise in building envelope optimization, thermal bridging solutions, and structural testing. As a former member of the heavy structure expert testing group at the University of Windsor, he contributed to innovative research in structural systems and building material performance. He also serves as a director of the Clay Brick Association of Canada (CBAC) and actively contributes to masonry standards development through participation in CSA and ASTM committees. He is also an engaged member of the Ontario Building Envelope Council (OBEC) and the Ontario Society of Professional Engineers (OSPE). He can be reached via LinkedIn

at www.linkedin.com/in/aarishkhan/.