Building up with lightweight wood frames

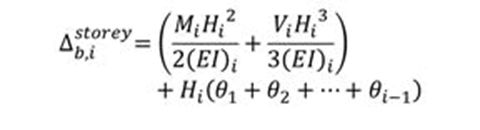

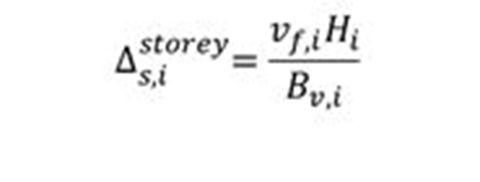

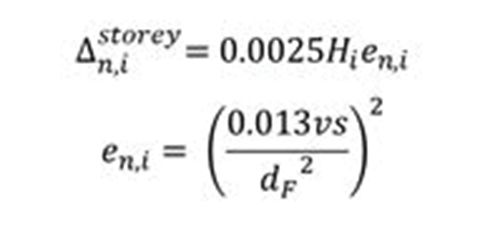

Deflection of a wood panel shear wall is made up of four components. These components are for additive and cumulative. Strik Baldinelli Moniz Civil and Structural Engineers found for most Ontario buildings, wind loads govern the deflection criteria while the seismic loads govern the strength design requirements. The deflection components include:

- bending of shear wall (Figure 7, below);

- shearing of shear wall, where Bv is the shear-through-thickness rigidity (Figure 8, below);

- slip of the nails in the sheathing, which is a function of load per nail and nail deformation (Figure 9, below); and

- slip/elongation of the hold-down anchorage, da, is provided by the manufacturer of the hold-down (Figure 10, below).

O86-14 and OBC 2012 code confirmation

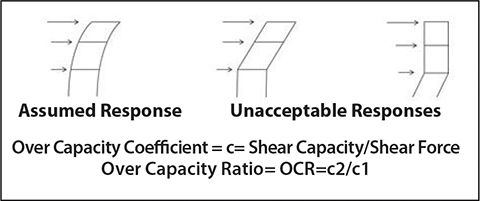

In combination with the strength and deflection checks, the program confirms all CSA O86-14 and OBC 2012 code requirements and is adaptable to other building codes around the world. If one of these design checks fail, the program will reiterate until the checks are satisfied. In accordance with these design checks, the program calculates the overcapacity ratio (OCR). This ratio is to confirm the assumed response of the structure is as intended between the first and second floor. The OCR values must be between 0.9 and 1.2 (Figure 11). The program also calculates torsional sensitivity. If it is sensitive to torsion and located in a high seismic zone, the building must be either stiffened or a dynamic analysis needs to be completed.

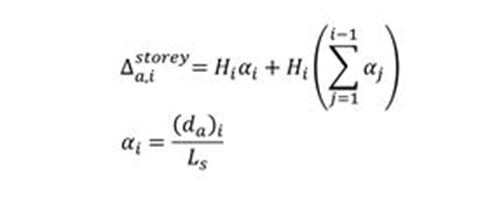

Seismic inter-storey drift is one of the other considerations calculated by the program. If the seismic inter-storey drift exceeds one per cent of storey height, gypsum cannot be used to brace studs or resist lateral loads. It is also important to note gypsum cannot be used to resist seismic loads in buildings greater than four storeys.

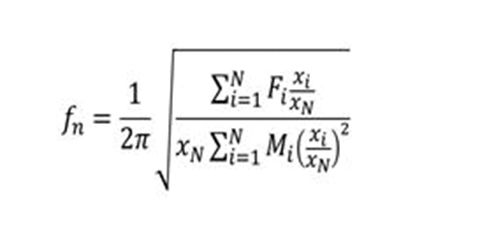

The final calculation of the program is the natural frequency (NF) of the building. Wind loading in the OBC is based on an assumption the natural frequency (Fn) is greater than 1 Hz. Determination of the NF is based on the deflection of the building—if the NF is less than 1 Hz, the building will either need to be stiffened or designed for additional dynamic wind loading (Figure 12).

Step five: Shear wall optimization

To take the program to the next level, material costs were incorporated. In many situations, firms are asked to change sheathing types, hold-down types, nail spacing, and shear wall locations long after the building has been designed. The design is complex and changes are not easy. To optimize the cost in conjunction with the design, a list of 180 different shear walls was assembled based on material and labour costs (panelized walls, supply only).

The shear wall types vary based on:

- stud size and spacing (e.g. 38 x 89 at 400 c/c 2-38 x 89 at 305 c/c, 38 x 152 at 305 c/c etc.);

- species type (SPF [spruce-pine-fur] or LSL [laminated strand lumber]);

- sheathing type and thickness; and

- nail size and spacing.

Based on these 180 wall configurations, a price per linear foot for each wall type was assembled, and the walls are ranked from least to most expensive. While the program selects walls to meet the strength and deflection requirements, it selects the least expensive wall first. If that wall fails, the next least expensive wall is chosen. This process continues until the program completes its design. Manual ‘tweaking’ is performed by the user to optimize the shear wall layout even further. Shear walls not participating efficiently are removed and the program is rerun. This process continues until the most cost-effective structure is designed, meeting all code requirements.

Cost analysis and case studies

To better satisfy the needs of clients, a detailed cost analysis was conducted to determine the costs of LWWF building versus traditional building products. The cost study was based on an existing four-storey LWWF that was just completed. Two levels were added to the structure and then re-designed. The designs were priced by a local wood panelization company. The following results showed the:

- cost of a four-storey, panelized wall/floor supply was $10.50/sf; and

- cost of a six-storey panelized wall/floor supply was $10.95/sf.

In an attempt to be impartial to other building materials, those values do not include installation costs, and other miscellaneous materials such as additional drywall to meet fire rating requirements, and concrete topping on floor joists to improve sound and fire ratings. When taking these items into consideration, an additional $8/sf should be added to both above costs for a total of $18 to $20/sf. Comparatively, Strik Baldinelli Moniz Civil and Structural Engineers recently completed design on two six-storey buildings composed of steel and concrete products, the framing costs averaged $28.85 /sf for the two buildings.

While it is clear there are savings in using LWWF construction, substantial savings can also be found in foundation design. To get a better handle on costs, the six-storey wood building was modified into a concrete building (same size and layout). A design was completed to get a better idea of foundation costs. The four- and six-storey wood building foundations were compared to the six-storey concrete building. When the ‘volume’ of concrete used for all three buildings was compared the:

- six-storey wood building had 10 per cent more concrete in its foundations compared to the four-storey wood building; and

- six-storey concrete building had 70 per cent more concrete in its foundations compared to the six-storey wood building.

During all comparisons, the soil conditions were considered to be ‘fair.’

The true costs of the foundation between the six-storey wood and six-storey concrete buildings would not be 70 per cent. The volumes do not take into account forming costs and labour, which would normalize the gap between the two costs. A significant savings in the foundation design can be achieved when comparing the two materials.

Similar studies have been performed on structures in British Columbia.(For more information about the British Columbian structures, see the Canadian Wood Council’s (CWC’s) Mid-rise Construction in British Columbia, WoodWorks’ A Case Study on the Remy Project in Richmond BC, WoodWorks’ Wood Solutions in Mid-rise Construction, and Altus Group’s Wood Brings the Savings Home: Construction Cost Guide 2014. ) In all studies, a savings of 10 to 12 per cent on the overall building construction costs were realized when compared to traditional building materials.

Next steps

The program has been used on six LWWF projects and has great success in controlling the building costs while maintaining all relevant code compliances. The ability to accurately calculate building deflections, inter-storey drift, overcapacity ratio, natural frequency, and strength parameters provides confidence that designs meet all CSA O86-14 and OBC requirements. The developers of the program have future plans to:

- create a Windows-based user interface for easier input and output capabilities;

- incorporate material take-offs for preliminary pricing purposes, prior to tender;

- use the program on an eight-storey LWWF building to determine sensitivity to building deflection and shear load interaction at floor diaphragms;

- prepare a paper for technical submission into a variety of engineering journals; and

- develop standalone finite element method (FEM) design software for LWWF buildings suited for all major building codes across North America.

SBM, in conjunction with the National Research Council (NRC) and Western University (London, Ont.) are commencing research into this design method. Phase I results are expected by the spring of 2016.

Michael Baldinelli is a principal with Strik Baldinelli Moniz, Civil and Structural Engineers. He has been involved in the design of more than 35 commercial (LWWF) lightweight wood-framed buildings in Ontario. Baldinelli recently lectured on behalf of the Ontario WoodWorks group on the structural design and optimization of multi-level wood buildings. He can be reached at mike@sbmltd.ca.

Michael Baldinelli is a principal with Strik Baldinelli Moniz, Civil and Structural Engineers. He has been involved in the design of more than 35 commercial (LWWF) lightweight wood-framed buildings in Ontario. Baldinelli recently lectured on behalf of the Ontario WoodWorks group on the structural design and optimization of multi-level wood buildings. He can be reached at mike@sbmltd.ca.