B.C. setting new standard for building energy performance

Images courtesy Energy Step Code Council

These projects are all increasing industry capacity to deliver on higher levels of performance. Training is ramping up across the province—most professional associations are offering hands-on and theoretical courses with engineers and architects at the forefront. For example, those two sectors played leading advisory roles on the BC Energy Step Code Builder Guide and BC Energy Step Code Guide, both published by BC Housing, the provincial housing authority.

The Vancouver Economic Commission’s recent Green Building Market Forecast concludes the BC Energy Step Code, in tandem with the City of Vancouver’s Zero Emissions Building Plan, may drive a $3.3-billion/year market for high-performance building materials in the province by 2032.

The study also projected the code could help create 925 well-paying, sustainable manufacturing jobs across Metro Vancouver and at least 770 ongoing installation jobs in the region.

Lessons from the BC Energy Step Code

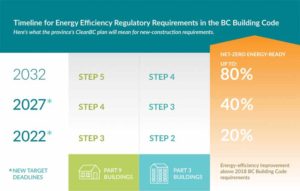

The Government of Canada has set a goal to make a model net-zero national energy code available for provinces and territories to adopt by 2030. Codes Canada’s Standing Committee on Energy Efficiency is on the case, and though the shape and form of that code are still under consideration, British Columbia’s approach could prove a template for a national code to follow.

With that in mind, earlier this year, the Energy Step Code Council has commissioned the report, Lessons from the BC Energy Step Code: How British Columbia became the first North American jurisdiction to create a regulated pathway to net-zero energy-ready buildings, to share key takeaways from the British Columbia experience with other provinces. They are briefly summarized here. For the full report, including explanatory diagrams, visit energystepcode.ca/publications.

Lesson 1: Pitch a big tent, and embrace shared leadership

Those interviewed for the report recommended other jurisdictions considering a tiered or stepped energy code understand the relative strengths and vulnerabilities of each built-environment stakeholder group, and equip them to serve as project champions.

For example, governments have very strong regulatory powers and resources, but are politically constrained. Professional associations of engineers, architects, builders, and building officials have extensive reach through their internal networks, but limited budgets. Utilities have excellent technical capacity, but no regulatory authority.

“Take an honest look at the actors around the table, and figure out who the leaders are, and what they need to take up the code and run with it,” one source said.

In the British Columbia experience, several interviewees confirmed professional associations help distribute information and education to members, and share experiences and issues with the larger group. For example, the council representative from the Urban Development Institute, representing the interests of developers, worked to actively share information about the BC Energy Step Code with other stakeholders and members via breakfast events.

Lesson 2: Set the end game, then backcast

Following early work done by the City of Vancouver and research conducted by the Pembina Institute, B.C.’s code authorities concluded “twiddling around the edges” of building codes would never get them to the ambitious target the government had set.

“We had started the process by explaining what we wanted the outcome to be,” one provincial government source said. “And we said to the stakeholders, ‘This is what we think the regulation should be in 10 or 15 years, now get to it. Work toward this very specific point.”

“This really snapped all the players into focus, and brought people on board who otherwise would not have been wild about the idea,” one interviewee said.

Lesson 3: Fear not the local governments

Traditionally, many provincial and territorial code authorities have hesitated to give local governments powers to regulate energy efficiency and lead a transformation of the built environment. However, British Columbia’s recent experience suggests those concerns may be misplaced, interviewees said.

When introducing code updates, provincial or territorial authorities typically move at the pace of the ‘slowest common denominator.’ However, the interviewees said this conventional approach overlooks the fact that large- and medium-sized communities have more capacity, experience, and also an interest in market transformation. Given bandwidth, resources, and peer support channels, local governments can be powerful and collaborative thought leaders, working with local designers and builders, and using the regulatory and incentive tools at their disposal.

| WHAT IS A NET-ZERO, ENERGY-READY BUILDING? |

|

Net-zero energy buildings produce as much clean energy as they consume. They are up to 80 per cent more energy efficient than a typical new building, and use onsite (or near-site) renewable energy systems to produce the remaining energy they need. In contrast, a net-zero, energy-ready building is one that has been designed and built to a level of performance such that it could, with the addition of solar panels or other renewable energy technologies, achieve net-zero energy performance. |