Assessing tough sustainability decisions: Informing expert intuition

by nithya_caleb | December 14, 2018 2:20 pm

[1]

[1]by Ian Ellingham, PhD, PLE, FRAIC

A major theme of our times is the powerful idea of sustainability. Yet, for the practical decision-maker working in the built environment, choosing between alternatives in an attempt to maximize project sustainability is rarely easy, because true sustainability involves fulfilling three frequently conflicting factors: economic, social and environmental. For example, if an existing project is not economically viable long term, it is likely to be demolished and the care put into achieving environmental sustainability will have been wasted. Searching questions must be asked, conflicting and uncertain information dealt with, and trade-offs made.

Even within the environmental factor, how might one balance resource utilization, energy consumption and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions? Ideally, some discerning analysis should be undertaken. Quantitative methods are important in moving towards real sustainability, and even a basic understanding of the principles behind them can help increase one’s capabilities as a decision-maker.

Making sustainable decisions

[2]

[2]Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons

We all make decisions, in our personal and business lives. Do we choose Alternative A or Alternative B, or look for something else? Choosing one thing almost inevitably means not selecting something else. Monetary resources are usually limited. Should money be spent on a higher-performing structural system or more prestigious floor finishes?

Humans make these sorts of decisions, but so do animals. Just think of the antics of your family dog: Does it go for the food or the friendly pat?

Sustainability is a complex concept, and is often misunderstood and misrepresented. A few key elements are worth keeping in mind. The fundamental feature of the concept of sustainability is how it deals with the longer term—ensuring society or some element of society can thrive over a protracted period of time. Decisions about buildings can have long-term implications, and those about urban environments even longer. One city councillor of a European city once said a big problem was the main roads into the city were established by the Roman administration when it was just a village of a few hundred people.

Sustainability implies considering intertemporal decisions, decisions relating and balancing flows of resources occuring at different times. We do something in the near future, in anticipation of someone receiving some benefit in the more distant future, or at least not having their future well-being undermined. As a result, many questions arise.

Objectives of an analysis

The objectives of an analysis for sustainability are reasonably clear, and in many ways are not much different from strictly economic objectives—both are seeking balance, neither overinvesting nor underinvesting. It is very easy to overinvest in the pursuit of environmental concerns, initially paying too much to achieve future benefits that may not materialize, or may be of little value to future generations.

Humans are very capable decision-making machines, capable of integrating more information and subtleties than any computer program (so far) and making judgments about risk and future possibilities, yet are also replete with biases and prone to fall into all sorts of traps. Different people will offer different opinions. How do you tell whose assessment is best? Hence one of the objectives of a quantitative analysis can be to verify decisions made on the basis of expert informed intuition.

Issues within an analysis

[3]

[3]Photo © Ian Ellingham

The first issue with an analysis is that of time. Most human-produced goods are relatively short lived—packaging, domestic appliances, cars, clothing—but buildings and infrastructure, and their implications, can last centuries. The flows of resources associated with buildings (money, energy, CO2, shelter) occur at widely different times. How does one perform a comparative analysis of things happening in different decades?

Future uncertainty is also an issue. The world of sustainability is infested with uncertainties, simply because we cannot know the future. Unfortunately, much discussion about sustainability makes the tacit assumption the future can be predicted with some accuracy. However, the track record of predictions regarding societal shifts is poor. One might consider the projections of the economist W.S. Jevons (1835-1882), who stated the industrial economy would collapse as it ran out of coal. Accepting a lack of reliable knowledge about the future forces the decision-maker to attempt to identify and discern the nature of the uncertainties likely to affect outcomes.

As one looks further into the future, things become progressively more uncertain. While we can make reasonable assumptions about conditions a few months in the future, in 10 or 20 years things are quite hazy. Twenty-five years ago, few people would have predicted the massive changes resulting from the Internet or its impact on our lives.

Hence, with respect to data, all that can be known with any degree of exactness is the initial situation. We might know, with some reliability, the costs of alternatives, and their very short-term implications, but even these costs can be undermined even by events between design and commencement of building operations. The decision-maker should attempt to understand how and why things might change, recognize the uncertainties and how to measure them, and make decisions recognizing that projections about a single future state will almost certainly be wrong.

Another issue is that in sustainability there is no single simple measure. Most analytical tools were derived from finance or economics, so are expressed in terms of money. However, if one conceptualizes resources on an abstract basis, the models remain a way of relating resource flows that might occur at different times. We expend (or do not expend) now in the expectation of someone receiving some benefit in the future. One can work these models on energy, CO2 emissions, natural resources, or anything else, although once one starts counting in multiple terms, one has to create relationships between them.

The basic analytical tool

[4]

[4]Discounting, the usual tool for comparing uncertain events occuring at different times, has its origins in the evaluation of financial assets. Many practitioners of environmental analysis tend to dismiss discounting. The reason for this is discounting is often misunderstood. It has its roots in the finance industry, and the decision-maker needs some insights into how discounting is applied in the context of the built environment. Discounting is often used to assess short-life products where time and uncertainty have limited roles relative to most consumer goods, but buildings are different because of their long and uncertain lives. If one ignores time and future uncertainty in decision-making, an event that might take place 1000 years in the future has the same weight as one happening tomorrow.

There are issues with discounting-based analysis, but recent refinements make it possible to use the method to gain better-quality insights into how to make decisions. The key factor in discounting is the rate, a number applied to uncertain future events to equate them to assured events in the present.

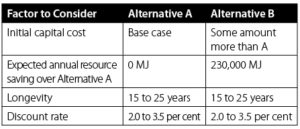

To illustrate how discounting can be applied, consider a simplified example where there is a choice between two pieces of mechanical equipment (Figure 1). One piece of equipment costs more, but offers ongoing savings in energy consumption, or some other resource flow. Without some reflection, the decision-maker might simply multiply the annual savings by some single life-expectancy, not recognizing the exposure of the decision to the life of the system.

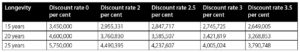

But the decision-maker does not know how long the equipment will last. If the use of the building or space changes, it might be retired long before it wears out. To attach some values to the example, let us say Alternative B saves 230,000 MJ of energy per year, compared with a more basic and cheaper Alternative A. The expected longevity of the equipment is 15 to 25 years. After 15 years, with no discount applied, Alternative B saves 3.4 million MJ. With a discount of 3.5 per cent to allow for risk, the savings would only be valued at 2.6 million MJ (Figure 2, page 80).

In discount-based analysis, what initially may appear as a single discount rate actually resembles a multilayer sandwich: a convenient assemblage of elements that makes numerical analysis reasonably tractable. These elements include:

- Fundamental time preference. This reflects a desire for value now rather than later, in a very simple, risk-free environment. This is rather like putting money on guaranteed deposit with a bank. We expect that with the interest earned we will have adequate compensation for not receiving the expected benefit of spending now.

- A less obvious component relates to the expectation of increased well-being over time. This is of particular importance when considering sustainable investment. This encompasses all those things that have, over the past few centuries, contributed to increased human well-being, including improvements in technologies.

- Beyond this is an allowance for societal risk, acknowledging society may not exist in a state to collect the future benefits of an investment. This includes such possible catastrophes as natural disaster, thermonuclear war, or societal collapse.

Social discounting is different than private sector discounting, as it relates to a wider circle of concerns, not the individual uncertainties associated with a company or a particular asset. In corporate settings, discount rates are much higher, usually because they include a large factor to deal with specific (or unique) project or corporate risk.

Thus, discount rates provided by company accounting offices should be viewed with some skepticism for purposes of sustainability decisions.

One source of estimates and insights into decision-making for the wider population is the British government guide to the assessment of policies, projects, and programs, entitled “The Green Book: appraisal and evaluation in central government.” It suggests the use of 0.5 per cent per year for fundamental time preference, 1 per cent for catastrophic risk, and 2 per cent to account for the wealth effect. This suggests investments made for the benefit of society are subject to a relatively low discount rate. A rate of 3.5 per cent is reasonable, and is generally accepted as the Social Time Preference Rate by the government of the United Kingdom, although the document does not oppose the use of a lower rate.

Do you accept this? Perhaps not, but understanding the factors that have to be dealt with in considering future resource flows can be helpful in itself.

[5]

[5]Photo courtesy NASA

More advanced techniques

Mathematical discounting only attempts to reflect human behaviour—how we, collectively and as individuals, deal with time and uncertainty. The reality is the human behaviour; the mathematics seeks to model it, so we can better assess alternative courses of action.

More importantly, any complete sustainability analysis has to allow for the possible presence of what are termed “real options.” This concept was developed in management research in the 1980s, and has become an increasingly important element in making business decisions. While quantified real options analysis can be a complex process, being able to understand the concept can be valuable to the decision-maker. The holder of a real option, typically a present or future decision-maker, has the right, but not the obligation, to take some action, perhaps expanding, abandoning, or changing the use of a building. Some real options may run with a project without being exercised for decades, and may be used, when deemed appropriate, by some future decision-maker. In some of this author’s work in real options, the Prince Edward Viaduct over the Don Valley in Toronto is used as an example. Completed in 1918, it incorporated provisions for a subway line, something not installed for 50 years. The decision-makers, before World War One, consciously paid to create this option. When we design resilience and flexibility into buildings we are doing much the same thing—making provision for things that might, or might not, happen. Interestingly, within an options framework, the value of that option did not depend upon whether it was actually used or not. The original decision-makers for the viaduct could not have been expected to predict the wars and economic turmoil that would occur over the next few decades. Real options in buildings frequently occur naturally; the challenge to the designer or property manager is in identifying them.

A commonly encountered real option is the possibility of waiting, deferring some action knowing it can be done in the future. Conceptually this is retaining the option to undertake the action. Mathematically, such an option may be worth more than the present value of exercising it immediately, especially when there is considerable uncertainty present. Waiting may provide additional information, the market situation may change, or new technologies may emerge.

While finance and management books present mathematical formulae to deal with uncertainty and to calculate option values, another route is to undertake Monte Carlo analysis. This involves the simulation of the decision alternatives and possible outcomes over time. Significant risk factors are incorporated in the model as estimated probability distributions, and the model is run multiple times, often thousands of times. This generates expected values, distributions, and confidence limits, which reflect the diversity of outcomes that may occur.

Building a simulation model using a spreadsheet program has the advantage of forcing the model-builder (hopefully, also the decision-maker) to identify and assess the nature of the situation over time, relevant risks, and risk distributions. It is possible, depending on the amount of time put into developing the analysis, to consider possible management responses to future events, in particular whether available real options might be exercised.

Interpreting the results

Relative to sustainability, in the construction world, no realistic method will give a clear single answer: there are just too many uncertain variables, and data quality is low. Every building is unique—even franchise fast-food restaurants are built on different sites. It is different in the financial area, where assets, such as stocks and bonds, are uniform, and minute-by-minute data may be available going back decades. For the construction decision-maker, poor and uncertain data means the outputs from any decision method will need interpretation.

Given the usual amount of uncertainty surrounding input data, sensitivity testing can be very revealing. This is the organized (or hopefully somewhat organized) varying of data inputs to explore the results. For example, one might make a base assumption about the life of a building or building component, but vary it to see how making it longer or shorter might change the preferred alternative.

[6]

[6]Returning to our earlier example of a choice between two pieces of equipment, to perform sensitivity testing, one might perform the calculations using various discount rates, and for various longevity values (Figure 2).

One issue with sustainability decisions is the presence of multiple measures: often the decision-maker has to consider energy consumption, CO2 emissions, initial costs, and operating costs. When dealing with these, sensitivity testing around equivalences can offer a further level of insight.

Monetary measures can be used to connect different measures within the context of the decision-maker’s priorities relative to sustainability. Scheme A might involve trading off some building feature to achieve a building with lower ongoing CO2 emissions. How much is being initially paid for this ongoing saving? Does it make sense? How does it compare with market values for CO2 emissions? One might make some assumptions about the situation regarding the relative value of future CO2 emissions, and test those assumptions to see how the results might vary.

The findings resulting from sensitivity analysis can sometimes be interpreted using the following logic. One outcome possibility (a) is the answer is fairly clear: Alternative A is preferred over Alternative B under any realistic data assumptions. Another outcome (b) is any difference in results is marginal. In this case, the data uncertainties and assumptions will prevent identification of one clear “best” answer and the decision-maker might choose on the basis of intuition. In between these two extremes is an area (c) in which one alternative is usually favoured, but not always. This warrants more consideration of the analysis, and perhaps more data collection.

The decision-maker

[7]

[7]Photo © Bigstockphoto.com

Consideration, and occasional use of quantified analysis techniques can help develop and confirm the capabilities of the decision-maker. A mathematical analysis can indicate whether the output results are consistent with the disaggregated beliefs of the decision-maker, in particular with respect to a collection of subjective input variables. Given the input data and assumptions, is the final decision appropriate?

Many of the managerial texts on using real options in other industries emphasize the benefits of laying out the elements behind the decision, even if the mathematical analysis is not undertaken. What are the key factors? What are the important elements of uncertainty? Do we have to make all the decisions now? Merely framing a decision will help draw out the key elements, and help inform one’s own experienced, informed, intuitive judgments.

It is worth having some humility. One does not have to make all the decisions now. Future managers will have more information, and probably better technologies. As well, one might be skeptical about predictions about the future, considering the predictions of the past: in the 1970s global starvation by the end of the 20th century was widely held as likely. Only a decade ago there were cries about “peak oil.” The problem is simply responding to some of these scenarios would have led to overinvestment and waste of resources. Waiting, when possible, and building real options through robustness and flexibility into a project is often a good strategy.

Perhaps the main reason a decision-maker should explore quantitative methods, is to develop the capability of making better decisions using only informed intuition. The building creation process contains myriad small decisions, so most will inevitably be undertaken without complete quantitative analysis. A comprehensive mathematical analysis might be justified relative to some decisions involving a major hospital or airport terminal, but not for a shop refurbishment. In the course of the author’s research, it has been found experienced decision-makers can make excellent decisions that it has taken the author days of data collection, model building, and analysis to replicate. It can be a long road to becoming a capable intuitive decision-maker, and ludicrous to spend 35 years of a career making poor decisions and then the last five making good ones. So we may need some help along the way. Understanding quantitative methods will help support experienced intuition, in particular the ability to frame decisions, and understand the key uncertainties that may determine outcomes.

There is a general consensus sustainability is a good thing, and yet it is rarely obvious how to achieve it, even with respect to one element of one building. Good decision-making tools are a key element in moving humankind to a higher level. Without such tools, decision-makers can be reduced to throwing collections of possible solutions at a problem, hoping something might stick.

| THE BASICS OF TIME AND RISK ANALYSIS |

| Discounting processes attempt to reflect human preferences. While the mathematics can appear to be exact, the entire concept is based on observations of human behaviour, so the beliefs of an individual decision-maker can vary from those of a client or of the wider population. This is one reason why sensitivity testing is so important especially with respect to sustainability. Recognizing time, ongoing uncertainties, and poor data is important.

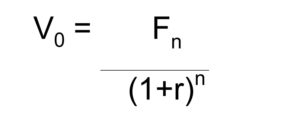

There are two key formulae for time and risk analysis. Some readers may recall these from school or continuing education sessions.

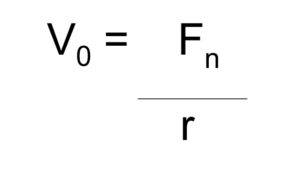

where, V0 = the value of some future resource flow discounted to the present; Fn = the value of some future resource flow at that future time; r = the discount rate being used; and n = the time (typically the year) of the resource flow, with n=0 being the present. The other formula yields the present value for an infinite resource flow, being:

While initially appearing somewhat unfeasible, given that few things last forever, this second formula allows useful shortcuts in many calculations. It is usually best to ignore inflation in matters of building sustainability. Even the economists cannot agree on long-term inflation. It can be included, but then it has to go into the discount rate being used. |

[10]Ian Ellingham, PhD, PLE, FRAIC, is an associate of Cambridge Architectural Research Ltd., a UK-based consultancy, and vice-president of Corinium Project Strategies, a Niagara-based property and consulting firm. He is the chair of the Niagara Society of Architects, and co-author of the books: Whole-Life Sustainability, London: RIBA Publishing, and New Generation Whole-Life Costing: Property and Construction Decision-Making Under Uncertainty, London: Taylor & Francis. He can be reached at ellingham.ian@gmail.com[11].

[10]Ian Ellingham, PhD, PLE, FRAIC, is an associate of Cambridge Architectural Research Ltd., a UK-based consultancy, and vice-president of Corinium Project Strategies, a Niagara-based property and consulting firm. He is the chair of the Niagara Society of Architects, and co-author of the books: Whole-Life Sustainability, London: RIBA Publishing, and New Generation Whole-Life Costing: Property and Construction Decision-Making Under Uncertainty, London: Taylor & Francis. He can be reached at ellingham.ian@gmail.com[11].

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/bigstock-City-Silhouette-Land-Scape-Ho-240665176.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/3.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Figure-1-sustainability-copy.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/belle-isle-detroit.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Figure-2-sustainability-copy.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/bigstock-210408265.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Formula-1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Formula-2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.constructioncanada.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/IanEllinghamPhoto.jpg

- ellingham.ian@gmail.com: mailto:ellingham.ian@gmail.com

Source URL: https://www.constructioncanada.net/assessing-tough-sustainability-decisions-informing-expert-intuition/

[8]

[8] [9]

[9]