Assessing tough sustainability decisions: Informing expert intuition

The decision-maker

Photo © Bigstockphoto.com

Consideration, and occasional use of quantified analysis techniques can help develop and confirm the capabilities of the decision-maker. A mathematical analysis can indicate whether the output results are consistent with the disaggregated beliefs of the decision-maker, in particular with respect to a collection of subjective input variables. Given the input data and assumptions, is the final decision appropriate?

Many of the managerial texts on using real options in other industries emphasize the benefits of laying out the elements behind the decision, even if the mathematical analysis is not undertaken. What are the key factors? What are the important elements of uncertainty? Do we have to make all the decisions now? Merely framing a decision will help draw out the key elements, and help inform one’s own experienced, informed, intuitive judgments.

It is worth having some humility. One does not have to make all the decisions now. Future managers will have more information, and probably better technologies. As well, one might be skeptical about predictions about the future, considering the predictions of the past: in the 1970s global starvation by the end of the 20th century was widely held as likely. Only a decade ago there were cries about “peak oil.” The problem is simply responding to some of these scenarios would have led to overinvestment and waste of resources. Waiting, when possible, and building real options through robustness and flexibility into a project is often a good strategy.

Perhaps the main reason a decision-maker should explore quantitative methods, is to develop the capability of making better decisions using only informed intuition. The building creation process contains myriad small decisions, so most will inevitably be undertaken without complete quantitative analysis. A comprehensive mathematical analysis might be justified relative to some decisions involving a major hospital or airport terminal, but not for a shop refurbishment. In the course of the author’s research, it has been found experienced decision-makers can make excellent decisions that it has taken the author days of data collection, model building, and analysis to replicate. It can be a long road to becoming a capable intuitive decision-maker, and ludicrous to spend 35 years of a career making poor decisions and then the last five making good ones. So we may need some help along the way. Understanding quantitative methods will help support experienced intuition, in particular the ability to frame decisions, and understand the key uncertainties that may determine outcomes.

There is a general consensus sustainability is a good thing, and yet it is rarely obvious how to achieve it, even with respect to one element of one building. Good decision-making tools are a key element in moving humankind to a higher level. Without such tools, decision-makers can be reduced to throwing collections of possible solutions at a problem, hoping something might stick.

| THE BASICS OF TIME AND RISK ANALYSIS |

| Discounting processes attempt to reflect human preferences. While the mathematics can appear to be exact, the entire concept is based on observations of human behaviour, so the beliefs of an individual decision-maker can vary from those of a client or of the wider population. This is one reason why sensitivity testing is so important especially with respect to sustainability. Recognizing time, ongoing uncertainties, and poor data is important.

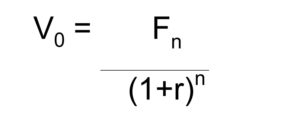

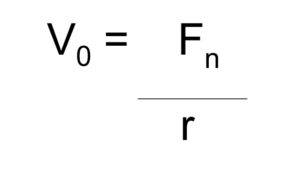

There are two key formulae for time and risk analysis. Some readers may recall these from school or continuing education sessions. where, V0 = the value of some future resource flow discounted to the present; Fn = the value of some future resource flow at that future time; r = the discount rate being used; and n = the time (typically the year) of the resource flow, with n=0 being the present. The other formula yields the present value for an infinite resource flow, being: While initially appearing somewhat unfeasible, given that few things last forever, this second formula allows useful shortcuts in many calculations. It is usually best to ignore inflation in matters of building sustainability. Even the economists cannot agree on long-term inflation. It can be included, but then it has to go into the discount rate being used. |

Ian Ellingham, PhD, PLE, FRAIC, is an associate of Cambridge Architectural Research Ltd., a UK-based consultancy, and vice-president of Corinium Project Strategies, a Niagara-based property and consulting firm. He is the chair of the Niagara Society of Architects, and co-author of the books: Whole-Life Sustainability, London: RIBA Publishing, and New Generation Whole-Life Costing: Property and Construction Decision-Making Under Uncertainty, London: Taylor & Francis. He can be reached at ellingham.ian@gmail.com.

Ian Ellingham, PhD, PLE, FRAIC, is an associate of Cambridge Architectural Research Ltd., a UK-based consultancy, and vice-president of Corinium Project Strategies, a Niagara-based property and consulting firm. He is the chair of the Niagara Society of Architects, and co-author of the books: Whole-Life Sustainability, London: RIBA Publishing, and New Generation Whole-Life Costing: Property and Construction Decision-Making Under Uncertainty, London: Taylor & Francis. He can be reached at ellingham.ian@gmail.com.